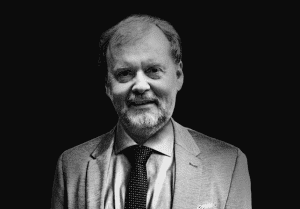

Larry W. Hurtado

(1943-2019)

Scholarship, Friendship, A Good Sense of Humor, Scottish Irrigation

Early in 1988 John Hollar at Fortress Press published Larry W. Hurtado’s One God, One Lord – or what Shannon, Larry’s beloved wife, fondly and irreverently calls “Oney God.” That book became an instant “must-read” for anyone trying to retrace the development of early Christianity. Alan Segal and Martin Hengel graced the book’s back with their estimations. Segal said Larry had written “one of the most interesting Christologies of the decade.” Hengel declared that Larry’s book signaled the formation of a new “Religionsgeschichtliche Schule.” Hengel was right; Segal was wrong. Larry had written a book that wound up lasting far longer than a mere decade, and Oney God was indeed the harbinger of a new approach.

I met Larry that fall. I had read his book, cover to cover, several times. I wrote him a letter asking all sorts of foolish graduate student questions and, typically patient Larry, he proposed to meet for coffee and a chat at the next SBL. Little did I know.

Elfin, bearded, bespectacled. Smart, serious, disciplined. Kind, generous, faithful. That morning in Chicago not only did I meet Larry and Alan, but they introduced me to Don Juel, Paula Fredriksen, Jarl Fossum, and several others at Larry’s insistence. Larry treated me like I was a new kid in school who needed to know everyone on day one. Looking back, 31 years later, 28 of which were spent rooming with Larry at the SBL, the features of Larry’s relentless scholarship, his love of his friends, and his penchant for mirth can be seen clearly, for they were all present, right there, brewed into that first cup of joe.

Larry’s beginnings, like most of ours who practice our peculiar craft, were humble and unimpressive. He received his first degree from an un-accredited Bible college. But it wasn’t where Larry started that mattered. It was where he ended up that counted–-an emeritus Professor at New College, University of Edinburgh, a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, the author of countless books and articles in a dozen or more languages, invited named lectures galore, and the recipient of high esteem from all of his colleagues on six continents. True, Larry did get an early leg up from the legendary Gordon Fee and, then, benefit from the exacting tutelage of the great Eldon Epp. These two not only instilled in Larry the love of the strange world of text criticism, but both Fee and Epp, and later Hengel, also modeled the sober, careful, and ridiculously thorough historical reconstruction that was to characterize Larry’s most important contributions. Larry effectively translated what he learned about the genealogy of ancient texts to investigate the evolution of early communities of Jesus followers.

Larry was a debater, and when I would complain about some scholar’s work, he would say, “change the question” and “ask the better question.” And change the question he did. No longer could people study Christology through the alchemy of titles attributed to Jesus or the endlessly exasperating “can it be proved that Jesus claimed something unique?” No. Larry changed the question from what was claimed by and about Jesus to a far more meaningful way to measure Christology. Larry changed the question to “what sort of devotion was publicly and repeatedly rendered to Jesus?”

Quite a lot, as it turns out. Larry demonstrated how prayers to and in the name of Jesus, baptism in the name of Jesus, preaching in the name of Jesus, holy meals and holy acts in the name of Jesus, and scriptures originally offered to/about God redirected to include Jesus—how all this and more—bore the freight of what early Jesus followers believed and, moreover, that these acts were the true measure of “Christ devotion.” For Larry, Christology was not early Jewish exegetical math which simply solved for x or a Christian chess match between masters of philosophical ontology. It was on the ground behavior. It was what early Jesus followers did—they worshiped Jesus while also worshiping God. Let the Christological chips fall as they may.

For Larry, this meant that early Jesus followers cannot be adequately described as just overly apocalyptically juiced Jews. No, early Jesus followers practiced their faith far differently than their ancestral co-religionists did. Nor can early Jesus followers be dismissed as simply mixing an exotic cocktail of Jewish messianic hope and Greco-Roman mystery religions or Emperor worship. No. No. For Larry, early Jesus followers were different from their ancestral co-religionist and from their pagan neighbors.

But to repeat the questions Larry asked (and recite the answers he gave) points to his most important work of scholarship, Lord Jesus Christ. Lord Jesus Christ was Larry’s Lebenswerk. In it, Larry set for himself one great task: to put the record straight. He took the full measure of Bousset’s Kyrios Christos, the book which had poured the footings and laid the foundation for the study of early Christianity for almost a century, and piece by piece, chunk by chunk, Larry broke it apart and then laid a new foundation. Lord Jesus Christ is the culmination and extension—and not simply the repetition—of scads of technical studies. Larry left no stone unturned in his quest to undo and redo Bousset. Simply put, Lord Jesus Christ is a big book. No, not just measured in girth. It is a big book because it has proven to be a field changing book. No one, for a good while to come, can begin (or end, for that matter) anywhere else but with Hurtado.

Early on, a year or two into our friendship, I was complaining that my paper proposal for a program unit had been turned down. Larry, trenchantly, devoid of pastoral care, simply said, “do better work.” I think I swore at him in response. But that’s what Larry did. From his humble beginnings to his last breath, he did better work—and more of it. He once told me he was flying to Germany for a lecture, but that he was going to stop over in London for three or four days. I asked why. He said, “oh, there’s several Oxford Phd theses I need to read.” I thought to myself, “who does that?” Well, Larry did.

Larry was as persistent in building community as he was relentless in his scholarship. From my first meeting on, Larry was always introducing me to someone else. He organized the Lightfoot reading group. He gathered people around a table at a pub. He was inclusive, generous, warm. He counted Bart Ehrman and Paula Fredriksen among his most cherished friends, even if what the three of them could actually agree upon would barely fill a thimble. He was a mentor, as his many students can attest, but he was also a sponsor. He discovered good scholars and he then worked on their behalf. He was curious. Always curious. He was a practiced listener – even if he himself could get on a roll (and stand aside when he did). He created community wherever he went. He remembered names of children, important events in the lives of others, he asked intelligent, thoughtful, and caring questions. If you were in Edinburgh, you were always welcome at the Hurtados. Shannon, to whom Larry was absolutely devoted, proved his equal in every way. Larry was a good cook. He loved his friends.

There was always a glimmer in Larry’s eye. He enjoyed a good joke and he was quick with a hearty laugh. The Program Unit Chair’s meeting in Nashville was marked by angst and anger. Seems no one had liked the venue, the prices, the isolation. Peter Richardson, who was slated to referee this rabble, was worried. Larry, right before the meeting told Peter simply to call on him first and he would break the ice. Peter did, and Larry did—by riffing a Cheech and Chong line that sent the whole room into several minutes of laughter. That was Larry.

For many years, a highlight of SBL was the annual meeting of the Early High Christology Club. A half -serious, half-social, half-scholarly, but fully raucous affair that included ample and equal amounts of laughter and single malt. At some high, holy moment, Larry would recite the founding myth of the club. There would be laughter, snickers, and each year the telling of the myth became more elaborate and ornate. Pauses. Side jokes. Larry held court. At the end of the sacred recital, he raised a wee dram to an Early High Christology and to departed friends. Alas. It is now time to raise one to Larry.

I called Larry the Saturday before he died on Monday. We talked for an hour. His voice was frail, halting, un-syncopated. He started talking about a book he was reading. He became animated. He fell back into that voice I had heard a thousand times. Confident, magisterial, commanding. Incisive. Rapid, agile, surefooted.

Down towards the end of the conversation I asked him about an email exchange from the previous week. I had commented that his faith was pig iron. He had been battling his health for two years, and he knew the end was near. He had responded that he was just playing craps.

I only partially understood his response (not uncommon, as Larry moved the pieces around on the board quickly) so I asked him about the reference to craps. He then told me the story of earlier in his career, at his lowest moment, without hope, and without any tangible future, in scholarship or any other livelihood, he had offered a prayer to God in which he questioned God’s purposes, and received what he said was an audible response, “I know what I’m doing, but I’m not going to tell you.” Larry laughed on the other end of the phone. “Isn’t that just like God? If you want to play craps, you have to play God’s game, because it’s the only game on offer.”

On Monday, Larry saw Death coming for him. With that same grit he had shown all his life, Larry stared Death right in the eye and asked, “Is that all you got?”

Scholarship, Friendship, A good sense of humor, Scottish irrigation—indeed. Here’s to you Larry.

Carey C. Newman