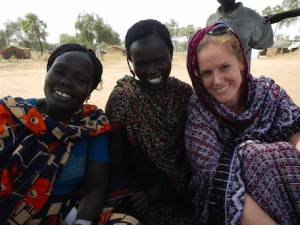

The author of this blog post is a missionary in North Africa with Pioneer Bible Translators. She, along with her husband and two little girls, lives on the outskirts of a refugee camp working to facilitate disciple-making, Bible translation and mother tongue literacy among two least-reached Muslim groups. Her favorite things about North Africa include drinking scalding hot mint tea, wearing colorful tobes, watching her daughters play on ant hills, and hearing people’s stories. Her least favorite things include rats in the kitchen and dry season dust storms.

The author of this blog post is a missionary in North Africa with Pioneer Bible Translators. She, along with her husband and two little girls, lives on the outskirts of a refugee camp working to facilitate disciple-making, Bible translation and mother tongue literacy among two least-reached Muslim groups. Her favorite things about North Africa include drinking scalding hot mint tea, wearing colorful tobes, watching her daughters play on ant hills, and hearing people’s stories. Her least favorite things include rats in the kitchen and dry season dust storms.

I first remember hearing the word sabur while sitting on a sagging rope bed in the suffocating shade of a tattered UN tent next to a woman who had just had her fourth stillbirth. She was just a friend of a friend at the time, a familiar face from the small community of Christians that meet under a tree here in the refugee camp, not someone I knew well. But when my close friend asked me to come to visit Om-Iman, the pretty young woman with the four dead babies, I was quick to say yes.

On this particular day I didn’t know exactly what to do or say. I had never sat with someone from my own culture who had just lost a baby before and sifting through my Arabic, which was neither of our mother-tongues, I felt clumsy and inept at communicating my deep sorrow for her loss. For a while Om-Iman spoke openly about how big the baby girl had been, how much blood she had lost, how long she must stay inside until her time of mourning has passed. As she spoke her voice was steady but tears trickled down the side of her obsidian cheeks while milk blossomed painfully against the cloth covering her breasts. I watched her, a woman whose life was marked with loss – born into a small tribe in a corner of the world where the government is actively trying to wipe her people off the face of the earth, not for the religion they share, but for the color of their skin. When the bombs became too much, she walked with her family for weeks through a wasteland to reach this sprawling refugee camp where there is at least usually food to eat. But like everyone around her, she feels every mile that separates her from home, and the thinly veiled tension with the host community. She has been here for four years.

So when she said the word sabur, I was taken aback. “But in this life we must have sabur, patience,” she said. “God sees everything, does he not? He has asked us to be patient. So we are patient.”

In my six years in North Africa I have learned a lot about patience. Patience with government officials who drag their feet issuing whatever stamp of the month we so desperately need. Patience with another rat in the kitchen. Patience with the care package from my mom that gets lost somewhere between the post office a country away and the bush plane that is supposed to deliver it to our dirt airstrip. And sometimes, when I am feeling especially spiritually mature, even patient with the wars, political instability and general blasted hardness of a context that forces us to keep reimagining what this ministry will look like.

But patient with four dead babies?

Patient when you can still hear the bombs falling across the border back home, and wonder who they hurt this time?

Patient as you wait out your life in a refugee camp and wonder if anything will ever change for the better?

I am learning so much from my North African brothers and sister and about patience. Sabur. The word holds so much more significance that simply waiting in a long line or trying really hard not to yell at your kids. There is something much closer to a word we might only here in an old translation of the Bible at church. Longsuffering. Enduring hardship for a long time. Sabur.

One might say that fatalism clouds much of what I see in women like Om-Iman. No doubt it is a mindset reality in huge swathes of Africa. But among these baby Christians here in the refugee camp where I have made my home, apathy is not what I see when they speak of patience. The tears and heart-wrenching cries at funerals, the singing and feasting at a new birth all seem like something much more alive to me. The patience I see strikes me as so close to something our Lord Jesus lived out. The willingness to encounter suffering not with anger or resentment, but with genuine grief and absolute trust in the goodness of God, even if it is hard to see at the moment.

Though there are certain things I chose to let go of in moving to North Africa, at the end of the day I still put a lot of trust in things other than God. The dark blue passport that gets me across most borders, the list of bush pilots phone numbers and the satellite phone to call them if the cell network goes down, a shelf full of antibiotics and home testing malaria kits. I still have my safety nets.

But women like Om-Iman don’t. They have their faith in God and the belief that he sees everything. And the fact that he sees is somehow in their favor. To be honest, there are days that the thought of God seeing everything doesn’t bring me great comfort. But for Om-Iman, it does. She will be patient, and in the end, God will make it all right. Because he is just and he is good. And this world clearly is not.

God is endlessly delighted in making the least into the greatest. And this barren refugee woman living out the beatitudes in the middle of war-town North Africa is my teacher in so many ways. I am drawn to her, not just out of my desire to be a bearer of hope for her and her community, but because I want to learn from her. People like Om-Iman are close to God’s heart in a way that I will probably never be. Many of us have been spared the circumstances in life that best teach patience. With grateful hearts, may we seek out those who understand it best, sit for a moment at their feet and learn just a bit of patience, true sabur.