Last updated on: January 1, 2020 at 7:14 pm

By

RJS

This time of year we can’t look at the book of Isaiah without considering the messianic prophecies in chapters 7 and 9.

Therefore the Lord himself will give you a sign: The virgin will conceive and give birth to a son, and will call him Immanuel. He will be eating curds and honey when he knows enough to reject the wrong and choose the right, for before the boy knows enough to reject the wrong and choose the right, the land of the two kings you dread will be laid waste. 7:14-16

The people walking in darkness have seen a great light; on those living in the land of deep darkness a light has dawned.

…

For to us a child is born, to us a son is given, and the government will be on his shoulders. And he will be called Wonderful Counselor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace. Of the greatness of his government and peace there will be no end. He will reign on David’s throne and over his kingdom, establishing and upholding it with justice and righteousness from that time on and forever. The zeal of the Lord Almighty will accomplish this. 9:2, 6-7

We skip ahead a little in Ben Witherington III’s recent book Isaiah Old and New: Exegesis, Intertexutality, and Hermeneutics to consider these two passages. Matthew quotes the first, likely from a Greek version: All this took place to fulfill what the Lord had said through the prophet: “The virgin will conceive and give birth to a son, and they will call him Immanuel” (which means “God with us”). (Mt 1:22-23) There are a number of issues with this quote. First, it is likely that the Hebrew text of Isaiah referred to a young woman of child bearing age, not explicitly to a virgin, although the Septuagint does make the reference to a virgin. There is also ambiguity in the phrase “and will call him Immanuel.” The term Immanuel is not always a proper name, it can just be a reference or a throne name “God with us.” The word is used in a slightly different context in 8:8 and 8:10. Finally, it is fairly clear in context that Isaiah had in mind a contemporary (perhaps Hezekiah, Ahaz’s son) rather than a future messiah. Hezekiah was, after all, a righteous king.

So was Matthew wrong? Ben Witherington has a rather different take on the question:

Surely, Isaiah did not have a full understanding of how these prophecies would later, and legitimately, be used by Christians. A prophet, in a poetic oracle, can say more than he realizes and it be part of the original meaning of the text, even though the prophet may not have realized the full significance of what he said.

Why, did Matthew turn to a text like Isaiah 7:14 LXX to explain the special and miraculous nature of Jesus’s origins since we have no evidence that prior or even later Jewish interpretation of this text thought it referred to a virginal conception? (p. 79)

While Isaiah was probably not referring to a miraculous conception in this sign for Ahaz, Matthew certainly was. Ben continues:

Here I think we have clear evidence that it is an event in the life of Mary that prompted a searching of the Scriptures to see if such a thing was presaged in the sacred texts. Put another way, since Isaiah 7:14 in the Hebrew or even in the LXX does not necessarily imply a miraculous conception, it must have been the miraculous conception in the life of Mary that prompted the rereading of the OT text in this way. In other words, this is not an example of a fictional story about Mary generated by a previous prophecy about a miracle. To the contrary, it is a reinterpretation of a multivalent prophecy in light of what actually happened to Mary. (p. 79)

Turning to the other passage quoted above, Isaiah 9:6-7 is not much cited in the New Testament, but it clearly played an important role in the understanding of the early church. While Matthew doesn’t quote these passages he does portray Jesus applying the opening of the oracle to himself at the beginning of his ministry (Mt. 4:13-16). John prepared the way of the Lord, but Jesus is the light, the Lord.

Again, Isaiah was likely referring to contemporary events, quite likely to Hezekiah, but he was also pointing beyond Hezekiah (who was after all a righteous king, but not a perfect king, and most definitely mortal). The vision is of an eschatological ruler who will do away with oppression and warfare. He is not a movie hero who shows up to save the day, but a vulnerable child who grows into the role. It is clear, Ben argues, that this is no ordinary human ruler even if Hezekiah is a foretaste, “the actual fulfillment of the promise comes in a later divinely appointed and divinely endowed ruler.” (p. 96) It is this ruler for whom the throne names Wonderful Counselor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace will ring true.

These titles are not mere rhetorical hyperbole if they refer to the future final eschatological king of Davidic ancestry. He will be the king of all kings, and the king to end all kings bringing the kingdom that will supplant all merely earthly kingdoms. (p. 97)

The hyperbolic language is a clue that this is not simply or only a prophecy about Hezekiah, even in Isaiah’s understanding. Isaiah knew that no human king would live up to the language. Isaiah “left the door open quite deliberately to look for eschatological fulfillment later.” (p. 100) Ben quotes J. J. M. Roberts from his commentary First Isaiah:

One cannot object that the Christian claims for Jesus grew out of a misconstrual of the original meaning of such prophetic oracles, because such an objection represents a serious misapprehension of the relationship between prophecy and Christian faith. A misreading of Old Testament prophecy did not lead the early disciples to belief in Jesus; rather it was the encounter with Jesus, with his life, his teachings, his death, and his resurrection that led them to read the Old Testament prophecies in a new way. (p. 100)

The oracles of Isaiah spoke in their own day with multiple layers of meaning, many of them likely intended and anticipated by Isaiah (e.g. 9:6-7) but others less so (e.g. Isaiah 7:14-16). The church rightly understood these passages afresh in the light of Mary’s experience and of the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus.

Does prophecy require an explicit intent for the final meaning?

How does Isaiah foretell the coming King?

If you wish to contact me directly you may do so at rjs4mail[at]att.net

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.

The links to books above above are paid links. Go with this one if you prefer: Isaiah Old and New: Exegesis, Intertexutality, and Hermeneutics.

Speaking of evangelism …

Speaking of evangelism …  If social science is more your bent … Elaine Howard Ecklund and Christopher P. Scheitle,

If social science is more your bent … Elaine Howard Ecklund and Christopher P. Scheitle,  Finally, Denis Alexander, molecular biologist, former chair of the Molecular Immunology Programme at the Babraham Institute in Cambridge and emeritus director of the Faraday Institute for Science and Religion, has recently published

Finally, Denis Alexander, molecular biologist, former chair of the Molecular Immunology Programme at the Babraham Institute in Cambridge and emeritus director of the Faraday Institute for Science and Religion, has recently published

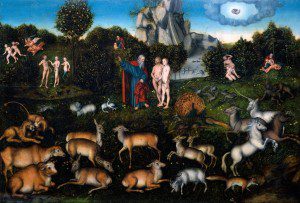

(2) Between the two positions above we have a range of views that maintain Adam and Eve as historical individuals while realizing that the issues raised by biblical evidence and mainstream science must also be taken into account. John Walton, Tim Keller, NT Wright, C. John Collins, Derek Kidner, John Stott, and many others fall (or fell) into this camp.

(2) Between the two positions above we have a range of views that maintain Adam and Eve as historical individuals while realizing that the issues raised by biblical evidence and mainstream science must also be taken into account. John Walton, Tim Keller, NT Wright, C. John Collins, Derek Kidner, John Stott, and many others fall (or fell) into this camp. Let’s Keep Our Eyes on Jesus. The key idea in Paul is not Adam, it is Christ. “Christ is the focus of Paul’s letters – and indeed the whole New Testament – not Adam.“(p. 92) How do we decide within the spectrum of views on Adam? “To answer that last question, let me repeat: the center of our faith is Christ, not Adam.” (p. 93) and then “as Christians we believe that redemption comes through the grace of Jesus Christ, received by faith. This is the universal answer for the universality of sin.” (p. 94) In the early church (second and third centuries) the origin of sin was not a particularly significant question, redemption through Christ was. If we keep our focus on Christ we realize that the question of Adam is a secondary issue. Although it may be an important question, it is a debate among orthodox Christians not a marker of heresy.

Let’s Keep Our Eyes on Jesus. The key idea in Paul is not Adam, it is Christ. “Christ is the focus of Paul’s letters – and indeed the whole New Testament – not Adam.“(p. 92) How do we decide within the spectrum of views on Adam? “To answer that last question, let me repeat: the center of our faith is Christ, not Adam.” (p. 93) and then “as Christians we believe that redemption comes through the grace of Jesus Christ, received by faith. This is the universal answer for the universality of sin.” (p. 94) In the early church (second and third centuries) the origin of sin was not a particularly significant question, redemption through Christ was. If we keep our focus on Christ we realize that the question of Adam is a secondary issue. Although it may be an important question, it is a debate among orthodox Christians not a marker of heresy.

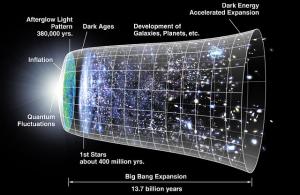

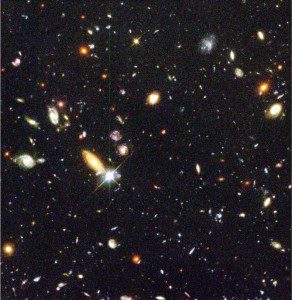

The Big Bang. The consensus view until rather recently supported an eternal static universe defined by regular cycles of time. Modern cosmology, i.e. big bang theory, points to a beginning before which the universe as we know it did not exist. Stephen Hawking, well known and accomplished physicist and cosmologist at the University of Cambridge, who died yesterday at the age of 76, put it like this (

The Big Bang. The consensus view until rather recently supported an eternal static universe defined by regular cycles of time. Modern cosmology, i.e. big bang theory, points to a beginning before which the universe as we know it did not exist. Stephen Hawking, well known and accomplished physicist and cosmologist at the University of Cambridge, who died yesterday at the age of 76, put it like this ( The fine-tuning of the universe is often taken as another argument for the existence of a creator (i.e. God). This, too, is a flawed argument. The fine-tuning of the universe is consistent with the Christian faith. We certainly expect that God, maker of heaven and earth, would have designed his creation as one hospitable for his purposes and thus for humankind. Greg puts it like this:

The fine-tuning of the universe is often taken as another argument for the existence of a creator (i.e. God). This, too, is a flawed argument. The fine-tuning of the universe is consistent with the Christian faith. We certainly expect that God, maker of heaven and earth, would have designed his creation as one hospitable for his purposes and thus for humankind. Greg puts it like this: