Luke Timothy Johnson concludes his recent book Miracles: God’s Presence and Power in Creation, with some pastoral advice – for pastors in particular. There are some great insights and ideas in this chapter. The problem is a serious one. It goes beyond a belief in Scripture to accept divine agency as a very personal reality.

The challenge facing contemporary Christians in the matter of miracles is daunting. … Incarnation and resurrection alike evade strictly evade strictly historical categories. Because they speak of divine agency in the empirical realm, they demand the language of myth. The same believers, especially pastors and preachers, are profoundly shaped by the worldview of modernity. Secularism has no place for the miraculous. For many calling themselves Christians today are more than difficult: they are intellectually embarrassing. (p. 277)

The answer isn’t intellectual assent to a literal reading of Scripture. As though miraculous activity and divine agency was merely an ancient fact to be believed … on faith. The answer is a re-focused approach to the whole topic of our faith in God’s divine agency in the world. Johnson suggests “four places in the church’s life, or four ecclesial practices, that can work together to shape such a symbolic world, within which believers can expect, perceive, and celebrate the manifestations of God’s presence and power in creation: teaching …, preaching, prayer, and pastoral care.” (p. 278) In these he speaks especially to those in leadership positions, with the responsibility to shape life together as a church.

The answer isn’t intellectual assent to a literal reading of Scripture. As though miraculous activity and divine agency was merely an ancient fact to be believed … on faith. The answer is a re-focused approach to the whole topic of our faith in God’s divine agency in the world. Johnson suggests “four places in the church’s life, or four ecclesial practices, that can work together to shape such a symbolic world, within which believers can expect, perceive, and celebrate the manifestations of God’s presence and power in creation: teaching …, preaching, prayer, and pastoral care.” (p. 278) In these he speaks especially to those in leadership positions, with the responsibility to shape life together as a church.

Teaching should shape and form people – and this requires an immersion in the world of Scripture. “Through whatever specific avenue of approach, we want Christians to learn how to imagine the world that Scripture imagines, how to cultivate a robust theology of creation, how to hear and honor personal experience, and how to appreciate the truth-telling qualities of myth.” (p. 279) Myth is not a synonym for fiction or falsehood – as though something is either historical or mythical. Rather myth is “language that seek to express what cannot be otherwise adequately expressed.“(p. 286) Neither science nor simple reporting of facts are adequate to describe and convey the full range of human experience. We need stories – the personal stories of fellow Christians and the ancient stories contained in Scripture. Stories that must be more than matter-of-fact reports.

When was the last time someone shared their testimony in your church?

Or the last time there was corporate prayer for specific needs?

When was the last community sing, taking requests from the congregation?

Is worship a sterile performance or a community experience of life together?

Johnson argues that sterilized Christianity, divorced from the real world lives of the people in the congregation, will never fully appreciate the truth of miracles, or of God’s agency in the world. “If the church, then, is to learn how to hear and appreciate the miracles in Scripture, it must learn how to hear and appreciate the miracles that occur in the lives of ordinary human beings both within and outside the church. … The church needs to recover the distinctive importance of personal witness, above all the witness to God’s working in human lives.” (p. 284)

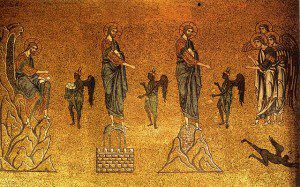

![]() Preaching and teaching are not the same – but they serve similar purposes in different ways. In a sermon he preached on the transfiguration and includes in this book, Johnson digs into the resonances between the experiences of Moses on Sinai and Jesus on Tabor. “The Gospel account of the transfiguration participates in revelation rather than simply reports it. The transfiguration story uses symbols of God’s presence and power to disclose deeper dimensions of the humanity of Christ.” (p. 291) The way we approach miraculous events in Scripture – as one-offs deep in the past, separated from the fuller story, and divorced from God’s agency in our world today – makes it hard to appreciate miracles for what they are, then and now.

Preaching and teaching are not the same – but they serve similar purposes in different ways. In a sermon he preached on the transfiguration and includes in this book, Johnson digs into the resonances between the experiences of Moses on Sinai and Jesus on Tabor. “The Gospel account of the transfiguration participates in revelation rather than simply reports it. The transfiguration story uses symbols of God’s presence and power to disclose deeper dimensions of the humanity of Christ.” (p. 291) The way we approach miraculous events in Scripture – as one-offs deep in the past, separated from the fuller story, and divorced from God’s agency in our world today – makes it hard to appreciate miracles for what they are, then and now.

My more important point is that God continues to reveal his presence and power just as truly in our world today. God is the ever-living God. The same God who created “in the beginning” continues to create at every moment and discloses his presence and power through what he brings into being. The same God who spoke through Moses also speaks through prophets and witnesses today. The same God who acted in Jesus Christ to heal and drive out demons continues to act in our world today to liberate and restore. (p. 292)

Prayer is an implicit and explicit acknowledgement of God’s divine agency today as in the past. “Prayer is more than a form of cognition: it is the activation of a relationship, moving the human person to the most explicit and naked stance possible before the mystery of existence, and calling out to the heart of that mystery, “God our Father!” (p. 296) Prayer makes it real … “Without the practice of prayer, the world imagined by Scripture is at best a fascinating construction of ancient minds; but with the practice of prayer, that world becomes an actual world in which to live.” (p. 298)

Pastoral care and counseling … getting into the messy lives of others when they need it most. When the preacher does not also participate in such pastoral care, the church is impoverished. Or so Johnson argues. Why? Because preaching isn’t simply a performance art and a preacher who is not engaged with the congregation cannot be fully aware of the power of God at work among the people. Miracles become extraordinary (past) events rather than the continuing reality of God at work today.

Miracles, as the title of Johnson’s book proclaims, are God’s presence and power in creation.

The church’s greatest gift and its mightiest challenge is to declare God’s self-revelation within the world that God brings into being, the One from whom creation derives, and the One to whom creation is ordered. Failure at this is utter failure. (p. 300)

Miracles, signs, and wonders are not just revelations in the deep past. God remains active today if we know where to look (and take the time and effort to do so). In our secular age we either discount miracles or attempt to explain them rationally. Ice floes in the Sea of Galilee might permit walking on water? Many Christian demand intellectual assent to the literal words of Scripture, but undervalue the power of God revealed in the story – and what it means for us today.

Johnson’s book is well worth reading. Miracles are a hard sell in our modern secular age. We know better – or so we are told. The approach of the fundamentalist – making assent to miraculous events in the deep past a litmus test for faith – doesn’t help matters. God’s divine agency is the heart and soul of Scripture. We need to tell the Story, not defend every detail. The incarnation is the pinnacle, the culmination of the Story in Scripture, but it isn’t the end of the story of God’s agency in the world. God continues to be active in his people. If we lose this, we’ve lost everything.

If you wish to contact me directly you may do so at rjs4mail[at]att.net

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.

The link to the book above is a paid link. Go with this one if you prefer: Miracles: God’s Presence and Power in Creation.

The pairings continue – with Simeon and Anna, the lost coin and the lost sheep, the parable of the persistent widow followed by the pharisee and the tax collector. The Twelve were all male – but for the most part the segregation stops there. Women were with Jesus and involved in his ministry from beginning to end, at the cross, the first at the empty tomb. And turning to Acts, they were with the apostles in Jerusalem where … They all joined together constantly in prayer, along with the women and Mary the mother of Jesus, and with his brothers. (1:14)

The pairings continue – with Simeon and Anna, the lost coin and the lost sheep, the parable of the persistent widow followed by the pharisee and the tax collector. The Twelve were all male – but for the most part the segregation stops there. Women were with Jesus and involved in his ministry from beginning to end, at the cross, the first at the empty tomb. And turning to Acts, they were with the apostles in Jerusalem where … They all joined together constantly in prayer, along with the women and Mary the mother of Jesus, and with his brothers. (1:14)

DDT was a miracle of chemistry … until the unintended side effects became apparent. The regulation and restriction of harmful pesticides has led in part to the rebound in the eagle population. The picture to the right is one I took when the eagle spotted its prey and took off from its treetop perch. Controlling mosquitoes is good. But we need to take care … not all effective methods are good.

DDT was a miracle of chemistry … until the unintended side effects became apparent. The regulation and restriction of harmful pesticides has led in part to the rebound in the eagle population. The picture to the right is one I took when the eagle spotted its prey and took off from its treetop perch. Controlling mosquitoes is good. But we need to take care … not all effective methods are good.

Moo and White move on to look at the things that are no longer (p. 158) …

Moo and White move on to look at the things that are no longer (p. 158) … But the sea and the night were not problems in Genesis. Rather they were a part of God’s good creation, and the sea is still a part of God’s good creation earlier in Revelation. This is one of the conundrums of the text and an issue that points us to the future and away from overly literalistic interpretations (always dangerous in apocalyptic literature anyway). The sea represents chaos and judgment in many parts of the Old Testament. Night is also a time of chaos and danger. Doing away with sea and night meant “for John’s readers the removal of all threat of judgment, all potential for evil to arise in the new creation.” (p. 160)

But the sea and the night were not problems in Genesis. Rather they were a part of God’s good creation, and the sea is still a part of God’s good creation earlier in Revelation. This is one of the conundrums of the text and an issue that points us to the future and away from overly literalistic interpretations (always dangerous in apocalyptic literature anyway). The sea represents chaos and judgment in many parts of the Old Testament. Night is also a time of chaos and danger. Doing away with sea and night meant “for John’s readers the removal of all threat of judgment, all potential for evil to arise in the new creation.” (p. 160)

Throughout his book Moberly has used passages from Aeneid 1 and Daniel 7 as case studies to discuss the privileging of the Bible. In the Aeneid, Jupiter bestows on Rome unending dominion over the world, “On them I set no limits, space or time: I have granted them power, empire without end” and establishes a descendant of Aeneas to rule the Roman empire and establish peace.

Throughout his book Moberly has used passages from Aeneid 1 and Daniel 7 as case studies to discuss the privileging of the Bible. In the Aeneid, Jupiter bestows on Rome unending dominion over the world, “On them I set no limits, space or time: I have granted them power, empire without end” and establishes a descendant of Aeneas to rule the Roman empire and establish peace. Daniel 7 describes a vision where one like a “son of man” comes before the Ancient of Days and is given dominion and glory and kingship – an everlasting dominion that shall never be destroyed. The Ancient of Days is understood to be Israel’s God. On the surface Aenied 1 and Daniel 7 are similar accounts.

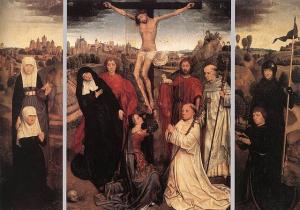

Daniel 7 describes a vision where one like a “son of man” comes before the Ancient of Days and is given dominion and glory and kingship – an everlasting dominion that shall never be destroyed. The Ancient of Days is understood to be Israel’s God. On the surface Aenied 1 and Daniel 7 are similar accounts. In Matthew 4 we read the well known story of the temptation of Jesus. The devil offers Jesus dominion if he will only worship him and Jesus replies “Away with you, Satan! For it is written: ‘Worship the Lord your God, and serve him only’.” Power and authority is not given by Satan or for the good of the one to whom it is given. We see this again on the cross and in the events leading up to it. Moberly highlights two passages. Matthew 16 where Peter recognizes Jesus as the Messiah, but then rebukes Jesus for saying that he, as God’s Messiah, must suffer. Peter’s response is very human “Never, Lord! This shall never happen to you!” Jesus turns to Peter, “Get behind me, Satan! You are a stumbling block to me; you do not have in mind the concerns of God, but merely human concerns.” But he has a word for the disciples (and us) from this interchange: “Whoever wants to be my disciple must deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me. For whoever wants to save their life will lose it, but whoever loses their life for me will find it.“

In Matthew 4 we read the well known story of the temptation of Jesus. The devil offers Jesus dominion if he will only worship him and Jesus replies “Away with you, Satan! For it is written: ‘Worship the Lord your God, and serve him only’.” Power and authority is not given by Satan or for the good of the one to whom it is given. We see this again on the cross and in the events leading up to it. Moberly highlights two passages. Matthew 16 where Peter recognizes Jesus as the Messiah, but then rebukes Jesus for saying that he, as God’s Messiah, must suffer. Peter’s response is very human “Never, Lord! This shall never happen to you!” Jesus turns to Peter, “Get behind me, Satan! You are a stumbling block to me; you do not have in mind the concerns of God, but merely human concerns.” But he has a word for the disciples (and us) from this interchange: “Whoever wants to be my disciple must deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me. For whoever wants to save their life will lose it, but whoever loses their life for me will find it.“