The Apostles’ Creed has more to say about Jesus than God, the Holy Spirit, or anything else.

The Apostles’ Creed has more to say about Jesus than God, the Holy Spirit, or anything else.

I believe in God, the Father almighty,

creator of heaven and earth.

I believe in Jesus Christ, his only Son, our Lord.

He was conceived by the power of the Holy Spirit

and born of the Virgin Mary.

…

I Believe in the Holy Spirit.

Yet the nature of Jesus as ‘his only Son our Lord’ was the focus of much controversy in the early church. The council of Nicaea was called to address the issue and the Nicene Creed, both 325 and 381, add much detail to the description.

We believe in one God,

the Father, the Almighty,

maker of heaven and earth,

of all that is, seen and unseen.

We believe in one Lord, Jesus Christ,

the only Son of God,

eternally begotten of the Father,

God from God, Light from Light,

true God from true God,

begotten, not made,

of one Being with the Father.

Through him all things were made.

For us and for our salvation

he came down from heaven:

by the power of the Holy Spirit

he became incarnate from the Virgin Mary,

and was made man.

…

And we believe in the Holy Spirit,

the Lord, the giver of life.

He proceeds from the Father and the Son,

and with the Father and the Son is worshiped and glorified.

He spoke through the prophets.

Concerning the person of Jesus 3 lines become 13. The description of the Holy Spirit also required elucidation – one simple statement becomes five lines. The Trinity is not an easy concept to understand. It wasn’t easy in the first few centuries of the church and isn’t easy today.

Without claiming to find modern science in the pages of the Bible, Andy Walsh (Faith Across the Multiverse: Parables from Modern Science) suggests that science – particularly quantum physics and the nature of light – can help us understand more about the nature of the trinity, and particularly mutual divine and human nature of Jesus as “true God from true God” … become incarnate and made man. Andy reflects: “While Jesus was on Earth, he described himself as “the light of the world” (John 8:12). Fitting, then, that we should examine different properties of light in order to understand Jesus better. … I find our present understanding of light provides a conceptual framework for further exploring what Jesus was like.” (p. 87)

Without claiming to find modern science in the pages of the Bible, Andy Walsh (Faith Across the Multiverse: Parables from Modern Science) suggests that science – particularly quantum physics and the nature of light – can help us understand more about the nature of the trinity, and particularly mutual divine and human nature of Jesus as “true God from true God” … become incarnate and made man. Andy reflects: “While Jesus was on Earth, he described himself as “the light of the world” (John 8:12). Fitting, then, that we should examine different properties of light in order to understand Jesus better. … I find our present understanding of light provides a conceptual framework for further exploring what Jesus was like.” (p. 87)

Light is not easy to explain. At times it behaves like particles – photons – that can be counted one by one. Yet these photons interfere – even with themselves – and behave like waves. Pass them through slits onto a screen and they diffract (the double slit experiment). Each individual photon goes to one place, but send a thousand through one at a time and an interference pattern emerges. Cover one slit and a completely different pattern is seen – even though in both experiments the photons can be separated by seconds – they don’t interact with each other at all. The same thing happens with electrons. It boggles the mind because photons, like other elementary particles including electrons and protons, behave in ways that do not fit into the neat categories we have based on our “normal” and macroscopic intuition. In fact, if we rely on our experience, the properties seem incoherent and irreconcilable.

As a physical chemist and spectroscopist, I find the wave-particle duality of electrons and photons a useful analogy to help understand a number of theological mysteries – and have used it before. Andy Walsh uses it to help understand the nature of Jesus as both human and divine.

There are three principle points Walsh makes.

First – we have to go with the data and not our reason and intuition. Walsh notes: “Just as we looked at various experiments that reveal properties of light, we’ll need to look at the data for Jesus we have from the Bible.” (p. 96) Some of the images we see of Jesus – emphasizing his human or divine characteristics – seem contradictory and may not fit our image of God. But Jesus, himself teaches us what it means to be human and divine. He also teaches us much about the nature of God.

Second – while we might tend to connect the three persons of the Trinity with the discrete particle-like nature of light, the properties of waves may also provide a useful analogy for how three can be one and one can be three. Although this seems contradictory from our particle-like understanding of personhood – it is not contradictory behavior for waves. Two or three waves combine to become one, one wave is easily decomposed into two or three or more. Now God isn’t a wave (as Walsh would agree) and the analogy is far from perfect – but it does point to the fact that three in one is not foreign to our experience if we know where to look.

Third – we can take advantage of interference to get a clearer picture of Jesus and of God. Large telescopes composed of multiple small mirrors rely on interference to produce a clearer image.

This ability to make a big telescope out of many small ones is quite handy, since it can be much more expensive to build a single large telescope than the equivalent array of smaller ones. It also handily paints a picture of how we can work together to understand God. Rather than trying to be the big telescope and see everything for ourselves, we can instead compare notes, see where our theological signals reinforce each other and where they cancel each other out, and infer from that combination a better picture of God than any one of us could see on our own. This is not equivalent to a lowest common denominator approach with a final image that is simply whatever is common to all observers. The interference from the combined signals is instead a careful and rigorous reconciliation of data from telescopes that are tracking together to look at the same part of the sky. (p. 101)

Among other thing those Christians who study God’s creation (scientists) and those who study Scripture (theologians and biblical scholars) working together should come up with a clearer picture than either group could alone.

Walsh concludes:

Having reflected on the nature of Jesus as both God and man and determined that, as with light, we need to let Jesus define our categories rather than be restricted to inadequate ones, we can apply those categories to our own lives. If Jesus is the ultimate expression of what it means to be human, then it is reasonable to orient our lives so that we are following his example. (p. 103)

It is not enough to understand God or Jesus better. We have to follow through and commit to that understanding of reality.

If you wish to contact me directly you may do so at rjs4mail [at] att.net.

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.

The communion of saints takes this one step further. Michael Bird notes “This communion exists

The communion of saints takes this one step further. Michael Bird notes “This communion exists

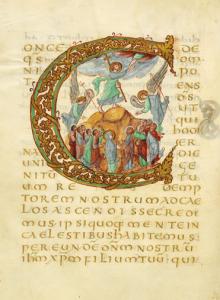

The bodily ascension of Jesus is anchor of our faith. Mike Bird points us to Hebrews 6:19-20 “We have this hope as an anchor for the soul, firm and secure. It enters the inner sanctuary behind the curtain, where our forerunner, Jesus, has entered on our behalf. He has become a high priest forever, in the order of Melchizedek.” Ben Myers focuses specifically on the bodily nature of the resurrection. The early church, beset by Gnostic heresies denigrating the flesh and spiritualizing both the resurrection and the ascension as a separation of the true Christ from the inferior material body, focused specifically on the resurrection and ascension of Jesus in the flesh. (

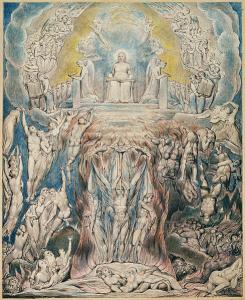

The bodily ascension of Jesus is anchor of our faith. Mike Bird points us to Hebrews 6:19-20 “We have this hope as an anchor for the soul, firm and secure. It enters the inner sanctuary behind the curtain, where our forerunner, Jesus, has entered on our behalf. He has become a high priest forever, in the order of Melchizedek.” Ben Myers focuses specifically on the bodily nature of the resurrection. The early church, beset by Gnostic heresies denigrating the flesh and spiritualizing both the resurrection and the ascension as a separation of the true Christ from the inferior material body, focused specifically on the resurrection and ascension of Jesus in the flesh. ( Future judgment. The section of the creed focused on Christ concludes with Jesus returning to judge both the living and the dead. The second coming is approached with trepidation by many these days. Certainly there has been a great deal of misunderstanding and faulty popularization over the last fifty years or more. The coming judgment, however, is a key affirmation of the creed and a fundamental part of Christian faith. Packer emphasizes the kind of judgment we are used to thinking about where are judged according to the Lamb’s book of life. “[T]he Creed looks to the day when he will come publicly to wind up history and judge all men-Christians as Christians, accepted already, whom a “blood-bought free reward” … rebels as rebels, to be rejected by the Master whom they rejected first.” (p. 106) (

Future judgment. The section of the creed focused on Christ concludes with Jesus returning to judge both the living and the dead. The second coming is approached with trepidation by many these days. Certainly there has been a great deal of misunderstanding and faulty popularization over the last fifty years or more. The coming judgment, however, is a key affirmation of the creed and a fundamental part of Christian faith. Packer emphasizes the kind of judgment we are used to thinking about where are judged according to the Lamb’s book of life. “[T]he Creed looks to the day when he will come publicly to wind up history and judge all men-Christians as Christians, accepted already, whom a “blood-bought free reward” … rebels as rebels, to be rejected by the Master whom they rejected first.” (p. 106) (