I am preparing for a discussion class on the Apostles’ Creed this Fall and digging into it in preparation. I will post on it occasionally over the next few months. Today I want to focus on two lines in article 3.

I believe in … the holy catholic church, the communion of saints, …

As it happens, my husband and I have been touring Germany the last two weeks, a mixture of business and pleasure. Three years ago we visited Lutherstadt-Wittenburg and I had an opportunity to attend an English service in the Castle Church. On this trip we’ve visited Schloss Wartburg (right) and Veste Coburg (below) where Luther spent time when the Protestant confession was being debated in Worms or Augsburg, and walked through a number of old churches (built in the 1200’s to 1600’s) in various towns. We visited churches in Leipzig where Johan Sebastian Bach originally directed music. We attended a Roman Catholic service in an ancient cathedral (one we particularly wanted to see and our only option was to attend a service). Not being fluent in German, one of the few things I recognized was a version of the Creed.

As it happens, my husband and I have been touring Germany the last two weeks, a mixture of business and pleasure. Three years ago we visited Lutherstadt-Wittenburg and I had an opportunity to attend an English service in the Castle Church. On this trip we’ve visited Schloss Wartburg (right) and Veste Coburg (below) where Luther spent time when the Protestant confession was being debated in Worms or Augsburg, and walked through a number of old churches (built in the 1200’s to 1600’s) in various towns. We visited churches in Leipzig where Johan Sebastian Bach originally directed music. We attended a Roman Catholic service in an ancient cathedral (one we particularly wanted to see and our only option was to attend a service). Not being fluent in German, one of the few things I recognized was a version of the Creed.

Travels around the world and immersion in the history of the Christian church drive home the importance of these two lines in the creed. Ben Myers in his new book The Apostles’ Creed reflects on the significance of the holy catholic church. While we may not believe in the pre-eminence of any particular institutional form of organization, it is an undeniable tenet of the Christian faith that we believe that the church is universal and composed of all who confess belief in God the Father, Jesus Christ the son and the Holy Spirit. We proclaim that the church is “catholic” because it is universal. Ben Myers writes:

The word simply means universal. It means that there is only one church because there is only one Lord. Though there have been many Christian communities spread out across different times, places, and cultures, they are all mysteriously united in one Spirit. Each local gathering is a full expression to that mysterious catholicity. (p. 103)

The catholic church does not distinguish rich or poor, male or female, social class or ethnic group. It is now and has long been translated into the vernacular language of any people.

But right from the start, the Christian movement was marked by translation. Jesus himself spoke Aramaic, but the four Gospels all translated his teaching into vernacular Greek so that the message would be available to as many readers as possible. Within a remarkably short time the Christian message had taken root in many different cultures, each one reading and proclaiming the gospel message in its own tongue. The message of Jesus is a catholic message. (p. 104)

Luther translated the Bible into German, working on his translation in both Schloss Wartburg and Veste Coburg. Although this was not the first such translation into German, the renewed emphasis on translation into the vernacular was one of the strengths of the Reformation.

Luther translated the Bible into German, working on his translation in both Schloss Wartburg and Veste Coburg. Although this was not the first such translation into German, the renewed emphasis on translation into the vernacular was one of the strengths of the Reformation.

The message of Jesus also transcends death. We are part of the communion of saints, past, present, and future. Many years ago on a trip to England, my husband and I happened on the cathedral in Durham and the grave and story of the Venerable Bede. This was important in my faith journey as it connected the history of the faith to the present in a way I’d never experienced before. It started with reading the works of Bede, then other older church fathers and has been refocused many times in many places. Although there are always elements of Christian belief and practice that are flawed in any time or place, there is also a depth of continuity to explore.

Myers elaborates on this idea of the communion of saints to emphasize that Christianity is a way of life rather than an institution.

[Jesus] was the author not of ideas but of a way of life. Everything Jesus believed to be important he entrusted to his small circle of followers. What he handed on to them was simply life. He showed them his own unique way of being alive – his way of living, loving, feasting, forgiving, teaching, and dying – and he invited them to live the same way. (p. 110)

Jesus was not establishing an institution or a new religion (this is a continuation of the same story!) Myers goes too far though, when he claims that Jesus did not lay down right answers to moral questions. The “right answers to moral questions” are part and parcel of the way to live. It is also where the church most often gets things wrong. The deep history of the church is our strength. But innate human focus on wealth and power as well as the corruption of sexual desire mixed with wealth and power has troubled and tainted the church from very shortly after its beginning. The history surrounding the Reformation gives us some of this, but we actually need look no further than the church today to see the truth of the matter.

J.I. Packer in his short meditation on The Apostles Creed combines these two phrases into one. The holy catholic church and the communion of saints both emphasize the universality of the church. The communion of saints, however, is more than the fellowship of Christians.

Some Protestants have taken the clause “the communion of saints,” which follows “the holy catholic church as the Creed’s own elucidation of what the church is, namely Christians in fellowship with each other – just that without regard for any particular hierarchical structure. But it is usual to treat this phrase as affirming the real union in Christ of the church “militant here on earth” with the church triumphant, as indicated in Hebrews 12:22-24. (p. 123)

He goes on to note that this may include communion in holy things such as word, Eucharist, prayer etc. and this is in line with the church as God’s community. The emphasis, however, on continuity with those who came before and those who come after is an important part of the church. We are situated in time and place, but not confined to only this reality. We overlook this reality when current fellowship is emphasized. As Americans, where history is relatively short, this really hits home when traveling in Europe or the Middle East. The communion of saints has a long history.

Although he doesn’t read the Creed as necessarily affirming universal Christian fellowship (i.e. community), Packer does see this as a fully biblical concept.

The church is the supernatural society of God’s redeemed and baptized people, looking back to Christ’s first coming with gratitude and on to his second coming with hope. (p. 124)

This doesn’t mean we can go it alone in worship and Christian life. He prefaces this statement with “as long as dominical sacraments are administered and ministerial oversight is exercised, no organizational norms are insisted on at all.” We need organized community of some form, with leaders trained in the faith.

Of course, the local church is a flawed human organization.

For the present, however, all churches (like those in Corinth, Colosseum, Galatia, and Thessaloniki, to look no further) are prone to err in both faith and morals and need constant re-formation at all levels (intellectual, devotional, structural, liturgical) by the Spirit through God’s Word. (p. 124)

When we remember the reformation (501 years after Luther gave his 95 theses in Wittenburg), we remember communion with those who came before in the history of the church, those who remain faithful in all denominations and structures, and the need to be always reforming to stay true as the people of God.

How do you understand “the communion of saints” in the Creed.

How does this impact your view of the church?

What is the function of the local church?

If you wish to contact me directly you may do so at rjs4mail[at]att.net

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.

John Walton and D. Brent Sandy (

John Walton and D. Brent Sandy (

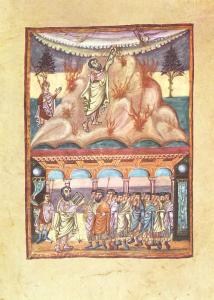

But destruction and re-creation did not establish order. Before we know it humans have again strayed. They start to build a tower to establish a relationship with God on their terms and to make a name for themselves. The story is ancient – it uses, John and Tremper note, appropriate technologies for something like 3250 to 2750 BC. The tower is a ziggurat – a structure in ancient Mesopotamia designed to allow the gods to come down to earth. The people are making an irreverent attempt to take control, bring God to them, and make a name for themselves.

But destruction and re-creation did not establish order. Before we know it humans have again strayed. They start to build a tower to establish a relationship with God on their terms and to make a name for themselves. The story is ancient – it uses, John and Tremper note, appropriate technologies for something like 3250 to 2750 BC. The tower is a ziggurat – a structure in ancient Mesopotamia designed to allow the gods to come down to earth. The people are making an irreverent attempt to take control, bring God to them, and make a name for themselves.