By Todd Dildine, who is a pastor at a small neighborhood church in Uptown, one of the most diverse neighborhoods in Chicago. He is most passionate about helping the church navigate the challenges of post-Christendom. Todd loves playing volleyball and he’s going to get married this summer!

By Todd Dildine, who is a pastor at a small neighborhood church in Uptown, one of the most diverse neighborhoods in Chicago. He is most passionate about helping the church navigate the challenges of post-Christendom. Todd loves playing volleyball and he’s going to get married this summer!

First, read Part 1 prior to Part 2. (Obviously.)

In Parts 2 – 4, I will be applying the Restoration Principle: For restoration to occur, the church must identify and address the forces that are attacking all communities (referred to as the “Anti-Community Forces,” or ACFs).

What qualifies as an “ACF”?

The collapse of the American community and church is a complex matter and has a variety of root causes. In this and the following two posts, I will address the three primary contributors to the downfall of community. I rely not just on my own observations but on the incredibly thorough and highly cited research of Robert Putnam, who has done the heavy lifting in identifying the ACFs most responsible for driving this trend.

But before diving in, it’s important to note that just because something seems destructive doesn’t automatically qualify it as an ACF. Just because kids flock to candy on Halloween doesn’t mean the holiday is responsible for juvenile diabetes. We need to keep our eye on larger systemic shifts.

There are two key aspects to primary Anti-Community Forces:

- They manifested around the last third of the 20th century, when data shows that participation in community-based activities began its long and steep decline. So as much as I would like to blame cats for the decaying of American communities, I can’t—Americans domesticated cats long before 1970.

- They must have a negative effect on community participation. This one should be obvious.

Identify the first ACF

Feel the ACF: Join me in this exercise. Imagine for a moment that all the cars in America and the technology to create them disappeared right now! (For scale: 88% of Americans own and use a car.)

Puff! Gone.

What does life look like for you tomorrow?

How are you getting to work?

How will you get to your favorite bar? Your coffee shop?

How will meet up with your friends?

What method of transportation do you take to see your parents, nieces, nephews, etc?

How will get to church?

How will you get your groceries?

Maybe you’re lucky enough to live near a commuter train for some errands. Otherwise, your bike would come in handy, and walking would be essential. But what if your church is 5-10 miles north, your job 10 miles south, and your friends and family 5, 10, 20+ miles in all directions? I don’t know what you would do, but I’d make efforts to decrease the distances between my spheres of life—for simple convenience, if nothing else.

The First ACF: Sprawl

Which leads me, naturally, to sprawl. Sprawl has become particularly relevant through the mass production and marketing of cars since the 1950s, which has allowed and encouraged human populations to decentralize. In 1945, car dealers sold only 70,000 cars; five years later, dealers saw an exponential growth and sold six million! This phenomenon led to the popularization of the suburbs in the 1960s, for as cars began to be integrated into our daily lives, city planners began creating new ways of organizing life and our city environment. They began expansion projects that allocated large swaths of land for single purposes: parking lots, shopping malls, and residential complexes, each space assigned for a different fragment of our lives.

What we know now is that as we began to shape our environment, our environment returned the favor. It began shaping us.

There are two primary effects of sprawl:

First: Sprawl zaps our time spent with others. The data is clear—there is a negative correlation between time commuting and community participation. In other words, the more you spend traveling to work in your car or train, the less you are involved in the lives of your friends, family, neighborhood, and church.

Second: Sprawl has stolen our concept of “place.” This restructuring of our lives has made it such that we merely inhabit space, with no concept of or regard for place. In fact, our understanding of place has effectively been completely disrupted by this distancing and fragmentation of our regular activities. This fragmentation accelerated exponentially during the growth of suburbanization. Clusters of houses were built that were cut off and separated from other aspects of life, such as work, shopping, and church—the only way to reach them was by car.

The issue with this? The less we care about the place we cultivate, the less we invest in it. The social fabric becomes more and more tenuous. My brother David Jenzen illustrates this phenomenon:

“We work ten miles away with people who live twenty miles beyond that, buy food grown a thousand miles away from grocery clerks who live in a different subdivision, date people from the other side of town, and worship with people who live an hour’s drive from another…we serve soup to the poor folks on the other side of the tracks, but we don’t know the person on the other side of the fence.”

This is the environment we have created for ourselves, and we have unintentionally embraced the consequences. The data is clear: Sprawl has created bad soil for growing closely knit communities.

To recap—sprawl has:

- Deceived us to believe that we can live far and yet remain close.

- Decayed our commitment to “place.”

Let me anticipate one push-back.

Q: Suburbanization is dying, and now people are returning to the urban areas.

A: Yes, people are moving back to urban areas. I am one of them. However, we aren’t regaining our concept of place when we re-urbanize. I know this to be true. My friends and church family are scattered throughout this great city of 2.7 million. Maintaining relationships is an uphill battle.

Addressing the Force of Sprawl

Along with the rest of culture, the church has fallen victim to the lie of sprawl, that a car could afford us the freedom to live anywhere and still have rich, flourishing community. The unfortunate truth is that the virus of sprawl inhibits the intimacy of fellowship (koinonia), swapping boundedness and boundedness for convenience and luxury.

I believe the way to address this ACF is simple: Choose to live close to one another. We need to understand that where we live has an impact on our community involvement and be intentional about where we live. I understand that many cannot simply move, but the many of us who can must choose to live near and with and for one another.

Urban, suburban, and rural areas will have different definition of “close.” One discernible principle to operate by: You are “close” to the degree that your kids can walk back and forth from each other’s house, without supervision.

Distance Matters: The Allen Curve

The Allen Curve essentially stipulates that proximity influences community participation. MIT professor Thomas Allen discovered that in the workplace there is a direct correlation between distance and frequency of communication between employees. The closer employees were to one another, the more frequently they collaborated. Conversely, the further employees were from one another, the less frequently they talked.

More recently, MIT is discovering that the Allen Curve is proving to stand true on a larger scale: on campus. The data finds that the closer in proximity researchers are on campus, the more likely they are to collaborate. Distance matters, proximity matters.

Similarly, the closer church members live to one another, the more we will communicate with one another. And the more we can communicate to one another, the more will have the opportunity to practice the 59 “one anothers” of Scripture.

As I interact with the research on sprawl’s damaging effect on community and the church, I’ve come to firmly believe that if Christians lived closer to one another, and chose to focus their life on a particular area, the church would experience a qualitative change necessary for restoration.

Identify ACF: Sprawl

Address ACF: Live closer to one another

Two necessary closing comments:

First. Proximity doesn’t equal community. To illustrate this, consider some studies show as high as 40% of married people report to being lonely*. But could you imagine a married couple who didn’t live in the same house flourishing as a couple? No, it’s not ideal. As the church, we live in the real, but fight for the ideal. Proximity may not equal community, but it’s like good soil: It permits community to flourish, but it doesn’t cause the rain to fall or the sun to shine.

Second: Sprawl has had a strong impact on community disengagement, but the next two ACFs are significantly more influential. We know this because we see similar levels of community disengagement and loneliness even in small towns and rural areas, where the effects of sprawl are not as pervasive,. So, as good investigators, we know that while impactful, sprawl must only be a fraction of the problem. There is more to this mystery to unfold.

Stay tuned for Part 3.

*Lars Tornstam. “Loneliness in marriage,” Journal of Relationships, 9, no. 2 (May, 1992): 197-217

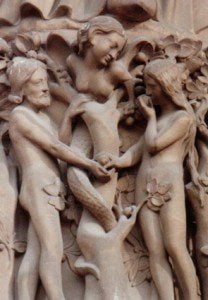

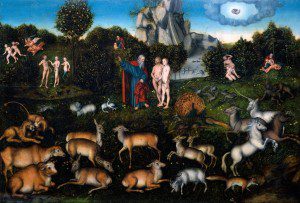

Genesis contains mythic and legendary elements in common with the ancient near eastern milieu of the original audience. The Fall is not a myth – but the text of Genesis is distinctly mythohistorical. It uses myth to convey truth. To read the text as strictly historical is to misinterpret the Word of God, to force our definition of what God would or would not inspire onto the text.

Genesis contains mythic and legendary elements in common with the ancient near eastern milieu of the original audience. The Fall is not a myth – but the text of Genesis is distinctly mythohistorical. It uses myth to convey truth. To read the text as strictly historical is to misinterpret the Word of God, to force our definition of what God would or would not inspire onto the text.