Is the universe fine-tuned, designed as it were, for our existence?

One of the key doctrines of the Christian faith is also the opening line of the Apostles Creed. “I believe in God the Father Almighty, Maker of heaven and earth.” Or the Nicene Creed: “We believe in one God, the Father Almighty, Maker of heaven and earth, and of all things visible and invisible.” God is the creator of everything that exists. Even time – defined by the material universe – is part of creation.

One of the key doctrines of the Christian faith is also the opening line of the Apostles Creed. “I believe in God the Father Almighty, Maker of heaven and earth.” Or the Nicene Creed: “We believe in one God, the Father Almighty, Maker of heaven and earth, and of all things visible and invisible.” God is the creator of everything that exists. Even time – defined by the material universe – is part of creation.

Does the universe contain evidence of design, evidence of the Creator? Greg Cootsona (Mere Science and Christian Faith) uses fine-tuning and the big bang to explore the relationship between science and Christian faith. Most importantly: should we expect science to prove the existence of God?

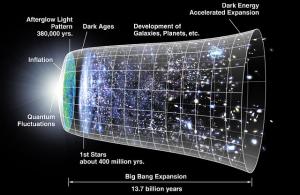

The Big Bang. The consensus view until rather recently supported an eternal static universe defined by regular cycles of time. Modern cosmology, i.e. big bang theory, points to a beginning before which the universe as we know it did not exist. Stephen Hawking, well known and accomplished physicist and cosmologist at the University of Cambridge, who died yesterday at the age of 76, put it like this (source):

The Big Bang. The consensus view until rather recently supported an eternal static universe defined by regular cycles of time. Modern cosmology, i.e. big bang theory, points to a beginning before which the universe as we know it did not exist. Stephen Hawking, well known and accomplished physicist and cosmologist at the University of Cambridge, who died yesterday at the age of 76, put it like this (source):

Since events before the Big Bang have no observational consequences, one may as well cut them out of the theory, and say that time began at the Big Bang. Events before the Big Bang, are simply not defined, because there’s no way one could measure what happened at them. … the Big Bang is a beginning that is required by the dynamical laws that govern the universe. It is therefore intrinsic to the universe, and is not imposed on it from outside.

Stephen Hawking made substantial contributions to our understanding of the universe. His book A Brief History of Time is one I thoroughly enjoyed when it first came out and still recommend. The Big Bang is consistent with the Christian doctrine of creation – time and space have a beginning. The beginning was long ago – 13.8 billion years – but it was a real beginning. Greg warns, however, that we shouldn’t make too much of this agreement. First, while it is clear that the universe is ancient and changing with time, it is possible that some future revision in our understanding of cosmology will point to a universe without a beginning. We could exist in one cycle of a periodic process. Second, a beginning is not in and of itself proof for a creator. If there is no God or creator then the beginning is simply a consequence of the laws of physics intrinsic to the universe, as Stephen Hawking believed. The big bang may bolster the faith of the faithful, but it is not likely to convince a skeptic of the truth of the Christian story.

What about fine-tuning? Greg supplies a definition of cosmic fine-tuning from Wikipedia (source):

The fine-tuned Universe is the proposition that the conditions that allow life in the Universe can occur only when certain universal dimensionless physical constants lie within a very narrow range of values, so that if any of several fundamental constants were only slightly different, the Universe would be unlikely to be conducive to the establishment and development of matter, astronomical structures, elemental diversity, or life as it is understood.

The fine-tuning of the universe is often taken as another argument for the existence of a creator (i.e. God). This, too, is a flawed argument. The fine-tuning of the universe is consistent with the Christian faith. We certainly expect that God, maker of heaven and earth, would have designed his creation as one hospitable for his purposes and thus for humankind. Greg puts it like this:

The fine-tuning of the universe is often taken as another argument for the existence of a creator (i.e. God). This, too, is a flawed argument. The fine-tuning of the universe is consistent with the Christian faith. We certainly expect that God, maker of heaven and earth, would have designed his creation as one hospitable for his purposes and thus for humankind. Greg puts it like this:

But is it a proof for God? Here’s where it’s easy to overstate the case. Some present the multiverse theory as a rejoinder-in other words, there have been innumerable attempts at other universes that simply failed. But since most of my colleagues in science tell me this theory is metaphysical speculation because it is in principle inaccessible to our scientific verification, I turn to philosophy for the strongest argument against fine-tuning as a p roof for God’s creation: it’s a tautology. Simply put, we are here in this particular universe. Whether its existence is perfectly calibrated or not, it’s the only universe we’ve got. It’s the only universe we know. In a sense, that makes the probability of its existence one hundred percent. …

This is not a deductive proof for God that leaves no room for disagreement. Instead it’s a suppositional argument that offers confirmation for the judgment that this universe has design and that design is confirmed, to some degree, by the incredible particularity of its parameters. If we suppose there to be a God who desired the universe, we should expect that this universe would have evidences of the design. The fine-tuning of various physical constants is therefore consistent with God’s design. Therefore it is reasonable to assert that God exists. (p. 79)

The bottom line is that we should be careful and open-handed in our integration of science and Christian faith. Although we affirm that God as creator is revealed in his creation, we need to be cautious in our conclusions. Greg provides four guidelines that I paraphrase and interpret from my perspective here.

- Scripture and nature give complementary perspectives on the nature of God. Greg notes that they are “not identical.” We shouldn’t be looking at nature to reveal much of the personal, relational nature of God or to Scripture to inform our scientific study of nature.

- Science is a changing discipline. Don’t make too much of an apparent agreement (e.g. the big bang) but don’t ignore the agreements and consistencies either.

- Keep up with developments so you don’t base your arguments on disputed ideas or conclusions that have been re-evaluated and revised in light of new evidence.

- Don’t jump on every new band wagon in science. Let the field mature before worrying much about it.

What do you see as the relationship between science and Christian faith?

What does it mean to integrate these two perspectives?

If you wish to contact me directly you may do so at rjs4mail[at]att.net.

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.

Jim agrees with Jeff that the traditional approach to natural theology is problematic. He also acknowledges that RTB has been successful with some people, but also notes that their concordist approach seeing scientific conclusions in Scripture isn’t universally persuasive even among the target audience of scientifically literate nonbelievers. He suggests that this is because the data are not clear and that there is always an element of interpretation as we consider Scripture and also the metaphysical implications of observations in nature.

Jim agrees with Jeff that the traditional approach to natural theology is problematic. He also acknowledges that RTB has been successful with some people, but also notes that their concordist approach seeing scientific conclusions in Scripture isn’t universally persuasive even among the target audience of scientifically literate nonbelievers. He suggests that this is because the data are not clear and that there is always an element of interpretation as we consider Scripture and also the metaphysical implications of observations in nature.