Some Christians see logic as the only trustworthy and effective way to communicate and receive knowledge. Unfortunately, there is not enough space in one post to systematically present the origins of this idea. In general, though the topic is a complex one, we can trace this concept from Ancient Greece, which gained momentum during the Enlightenment, through present Western thought.

Some critics of Ruth A. Tucker’s book, Black and White Bible, Black and Blue Wife: My Story of Finding Hope after Domestic Violence, have likewise privileged logic over emotion. For example, in their reviews of Tucker’s book, Tim Challies, Melissa Kruger, and Mary Kassian all argue against Tucker’s emotional argument, dismissing it as a weaker approach to the topic of abuse.

Challies engages positive aspects of the book, though he nullifies his positive words with his final refusal to recommend it. Kruger and Kassian are less gracious in their opinions, focusing only on the book’s weaknesses, while implicitly throwing shade in Tucker’s direction for being too emotion-based.

Let’s take a closer look. Each reviewer critiques Tucker’s thesis as being based solely on her experiences and feelings. For example, Challies writes, “The first weakness is… that to some degree Tucker defines an entire theological understanding out of her own experience.”

Kruger and Kassian have the same concern as Challies. Kruger comes at Tucker hard. In one brief section, she states that Tucker’s thesis “is based on her experience… The only evidence that Tucker offers is her own experience… Tucker essentially feels that complementarian thinking led to her abuse and so it must be true” [emphasis Kruger’s]. It seems that Kruger does not attribute any critical thinking abilities to Tucker, despite Tucker’s successful career as a scholar. Still the redundancy in this section is intriguing, particularly when compared to the other reviews.

Kassian also emphasizes Tucker’s experience: “So Ruth’s experience and my experience testify to the exact opposite conclusion. Which is why experience and emotions are an unreliable source for debating the veracity of a premise. It’s a sad day when reason is ignored and a conclusion accepted purely on the basis of who tells the best story and evokes the strongest emotion” [emphasis mine].

And then there is this: “The difficulty with an emotionally-charged narrative style of argument is that it doesn’t lend itself well to objective analysis.”

Challies also challenges the validity of Tucker’s experience-based argument for her position. Tucker responded to Challies’ review and his concern about her experience. She writes, “I’m wondering why you would twice reference ‘her own experience’ in this short paragraph in relation to my ‘entire theological understanding’ of complementarianism. I did know, however, that by the title and content of the book I was setting myself up for this type of criticism.

I might take this as a gender put-down, but I’ll try not to. Neither will I suggest that the one who speaks against egalitarianism does so out of ‘his own experience.’ Nor do I think that I am more guilty of emotionalism than, let’s say, someone like John Piper. You state: ‘In fact, the proof she offers for her position is often emotional rather than biblical.’”

And this exchange shows part of our difficulty. Can emotions be revelatory? Can they provide insights and truths that align with and support biblical truths?

Kassian argues that emotions and experience are an “unreliable” means to determine the truth of a claim. Yet, are they?

It depends on the claim being made. For example, if the claim is simple, such as, “That lemon is sour,” then my experience tasting it and the resulting feelings I experience are reliable to determine the truth of that claim unless, as C.S. Lewis suggests, we do not experience the lemon as sour. In that case we have only two logical choices: either something is wrong with the lemon or something is wrong with one’s taste-buds. For Lewis, our subjective feelings should correlate with the objective reality we encounter. If they don’t, well then we need to work on training them to respond rightly, as well as help train others—hence the Narnia books.

My point in referencing Lewis is simply this: emotions and experiences are not inherently unreliable. Neither are logic and reason inherently infallible. Emotions, like logic, either correspond to reality or they don’t. We are responsible for analyzing and discerning truth claims, whether they are propositional or narrative. And significantly, the Bible that God provided for us is mostly narrative and poetry. Propositional statements occur far less often.

Would Kruger level this accusation against Dinah, Tamar, or the Levite’s concubine? She writes, “As sympathetic as I am to [their] abuse, I find this type of experiential argument manipulative and unhelpful.” Perhaps she does find those biblical stories unhelpful. They are certainly difficult and painful to engage. But that’s the point isn’t it?

Scripture informs us that human emotions are an effective means to sense and respond to reality. And many Bible women used emotional appeals to demand justice in an unjust world. Yet, we are asked to trust those appeals when we read them in Scripture.

I believe that an “emotionally charged narrative style” can provide an objective analysis. In fact, emotional appeals are one of the three types of rhetorical appeals—ethos, logos, and pathos—that speakers employ to persuade others to their argument.

To be clear, I am not talking about a manipulative spin of facts or information to produce emotionalism from an audience. Pathos has to do with emotions, but emotional appeals can be used in arguments both ethically and logically.

Now many of us, including myself, are suspect of emotional appeals. Our culture’s ubiquitous advertisements, among other things, have made this wariness a necessity. Even so, instead of merely dismissing emotional appeals, or narrative styles of argument, we must learn to engage them ethically and discern whether or not they have substance and correlate to reality.

Now perhaps, some readers are thinking that if all three reviewers brought up Tucker’s emotions and experience so much, then perhaps there is some weight to their criticisms. Fair enough.

Yet, if one is going to argue against another’s emotional appeals then one must be able to show why it is manipulative, or shallow, or not an accurate reflection of reality. In other words, one needs to show why it is not an effective or ethical emotion appeal. It is not enough to state that the appeal is too emotional, or too experiential, or too manipulative. If you cannot analyze and explain how an emotional appeal is manipulative or shallow, then you have not formed a sufficient counter-argument.

So by all means let’s engage logical thinking and writing. Let’s research and analyze to our hearts’ content. But let’s also recognize the value of emotions and experience. And let’s engage both ethically, with discernment, while not worshipping either.

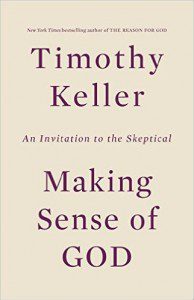

Perceived Design. This is a fine-tuning argument. The universe has a range of precise characteristics that make the existence of life possible. Many people have argued that the probability of all these parameters having exactly the right values is incredibly small, maybe 1 in 10100. It seems incredible that this is just a lucky accident. The multiverse hypothesis, that there are many different universes with different parameters and we are (of course) in the one that is just right, is one proposed solution to this problem. But it is a hypothesis to account for a phenomenon that could equally well be accounted for by the existence of designer. “So, believers in God argue, as long as you don’t beg the question and assume that God could not possibly exist, then the fine-tuning of physics makes more sense in a universe in which there is a creator and designer.” (p. 219)

Perceived Design. This is a fine-tuning argument. The universe has a range of precise characteristics that make the existence of life possible. Many people have argued that the probability of all these parameters having exactly the right values is incredibly small, maybe 1 in 10100. It seems incredible that this is just a lucky accident. The multiverse hypothesis, that there are many different universes with different parameters and we are (of course) in the one that is just right, is one proposed solution to this problem. But it is a hypothesis to account for a phenomenon that could equally well be accounted for by the existence of designer. “So, believers in God argue, as long as you don’t beg the question and assume that God could not possibly exist, then the fine-tuning of physics makes more sense in a universe in which there is a creator and designer.” (p. 219) Beauty. We have an indelible sense that beauty is real. Flowers, birds, a lush jungle, a barren dessert, the sunset. It is hard to explain our sense of beauty as an artifact of evolution. Certainly some ideas of beauty could be related to food and mating, but far from all. “In fact, to find something useful is to see it as a means to an end, but to find something beautiful is different. It is marked by “utter gratuity.” It is deeply satisfying immediately, in itself, not for anything it does for us.” (p. 226)

Beauty. We have an indelible sense that beauty is real. Flowers, birds, a lush jungle, a barren dessert, the sunset. It is hard to explain our sense of beauty as an artifact of evolution. Certainly some ideas of beauty could be related to food and mating, but far from all. “In fact, to find something useful is to see it as a means to an end, but to find something beautiful is different. It is marked by “utter gratuity.” It is deeply satisfying immediately, in itself, not for anything it does for us.” (p. 226)

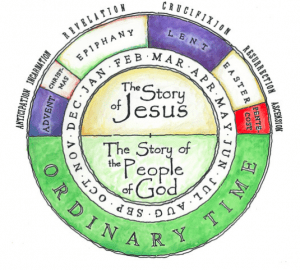

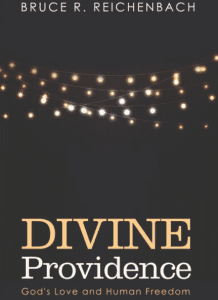

I am leading an adult Sunday morning discussion class this winter that digs into the question of interpretation, looking for the full depth of meaning in Scripture. One of the primary resources we are using (after the Bible itself) is

I am leading an adult Sunday morning discussion class this winter that digs into the question of interpretation, looking for the full depth of meaning in Scripture. One of the primary resources we are using (after the Bible itself) is