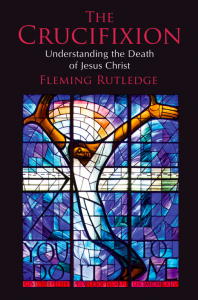

Jason Micheli will be posting reflections on Fleming Rutledge’s new book, The Crucifixion: Understanding the Death of Jesus Christ, through Lent. Jason is a United Methodist pastor in DC who blogs at www.tamedcynic.org

Jason Micheli will be posting reflections on Fleming Rutledge’s new book, The Crucifixion: Understanding the Death of Jesus Christ, through Lent. Jason is a United Methodist pastor in DC who blogs at www.tamedcynic.org

A year and a half ago Hannah Graham, a UVA student from my parish, went missing near her campus. Weeks later her body was found. She’d been assaulted and brutally murdered.

Theologically, I’ve always been committed to the sheer nothingness of evil. Rather than a thing with any substance or subsistence of its own, the tradition holds that evil is absence. Maybe evil is the privation of the good, as Augustine thought it, but during the prayer service I led in the days when Hannah was still missing, when everyone hoped for the best but suspected the worst, the presence of sin and evil was felt palpably throughout the sanctuary. In the months since then the devastation and trauma felt from her murder have grown and festered. I’ve watched with sadness and something like righteous anger as many of Hannah’s friends in my congregation continue to struggle with depression, despair, and a loss of faith. Two weeks ago, when it was reported that Jesse Matthew, her accused murderer, had decided to plead guilty, I rejoiced confident that God rejoiced too now that Hannah would receive at least this measure of justice.

My takeaway from this experience:

A vital refrain of scripture gets obscured when we individualize and moralize sin.

Sin costs something.

Sin must be atoned for.

Yes, Jesus enjoins us to forgive as much as 70 x 7 times, but sin, like the sin done to Hannah and the entire community who loved her, requires justice too. As my mother used to tell me, ‘Saying sorry doesn’t cut it. You’ve got to repair the damage you’ve done.’ Even for my mom, repair required sacrifice.

It’s right, even holy, to rejoice that Jesse Matthew will pay for the damage he’s done.

Sin costs something. This is the convicting acknowledgment running through the rituals of sacrifice in the Book of Leviticus. Counter to the popular complaint about traditional atonement theories which asks, flippantly, ‘Why can’t God just forgive?’ the fundamental presupposition of Leviticus is that there must be atonement for sin. Put aside distracting conceits like God’s offended honor and simply focus on the concrete, real-world devastation wrought by sin.

As Fleming Rutledge argues in her book, The Crucifixion:

‘Sin can’t just be forgiven and then set aside as though nothing has happened. If someone commits a terrible wrong, Christians know that we are to forgive; but something in us nevertheless cries out for justice. The Old and New Testaments both speak profoundly to this problem. It is not enough to say, ‘Mistakes were made, or ‘I didn’t mean to’ ; the whole system in Leviticus is set up to prevent anyone from thinking that unwitting sin doesn’t count.’

In Part 2 of The Crucifixion, Fleming Rutledge examines at length the primary atonement motifs (her preferred term over atonement theories) in the biblical narrative. She gives considerable attention to the motif of blood sacrifice, seeing it not only as the foundational motif upon which many other atonement motifs depend but also because blood sacrifice, along with passover, is the primary lens through which the early Christians interpreted the death of Jesus. They did so, after all, because ‘their single source for discovering the meaning of the strange death of their Lord was the scriptures they had always known.’

They grappled with the meaning of Christ’s death in the terms available to them, in other words, and in their scriptures blood sacrifice was a recurring motif for understanding how sinful humanity is brought near to their God. In particular, the Book of Leviticus became fertile ground for interpreting the terrible mystery of the cross. As Rutledge imagines:

‘It must have been a very exciting process. Anyone reading Leviticus and thinking of Jesus at the same time could hardly fail to notice a phrase like ‘a male without blemish’ in the list of stipulations. This is the sort of detail that would would jump off the page of the Hebrew Scriptures in those first years after the resurrection.’

Mainline and progressive Christians frequently express disdain for the blood imagery of scripture. We judge it, snobbishly Rutledge thinks, to be primitive; meanwhile, we let our kids play Black Ops 3, we fill the theaters for American Sniper, and we refer to those innocents killed by our drones as ‘bugsplat.’ That is, if we care about the droned dead at all. We exult in gore and violence in our entertainments, but we feign that we’re too fastidious to exalt God by singing ‘There’s a Fountain Filled with Blood.’ Rare is the Christmas preacher bold enough take the Slaughter of the Innocents as his text while the Washington Post app on my iPhone makes it uncomfortably obvious that the slaughter of innocents goes on every day. Never mind that in its use of blood imagery, scripture remains reticent, refusing to dwell in gore by focusing instead on the effects of the sacrificed blood.

In our disinclination towards the language of blood and sacrifice, treating it as a detachable option in atonement theology, Christians today could not be more different from the writers of the Old Testament who held that humanity is distant from God in its sin and atonement is possible only by way of blood. Viewed from the perspective of the Hebrew Scriptures, we make the very error Anselm cautions against in Cur Deus Homo. We’ve not truly considered the weight of sin.

My friend, Tony Jones, recently featured a guest post on his blog from someone who advocated altering the traditional serving words for the eucharist (The body of Christ broken for you. The blood of Christ shed for you.) to ‘Christ is here, in your brokenness. Christ is here, bringing you to life.’ Or, ‘Christ broken, with us in our brokenness. Christ’s life, flowing through our lives.’ Such redactions just won’t do the heavy lifting if one is committed to taking seriously the language of scripture. While the traditional imagery of blood sacrifice may make some squeamish, Fleming Rutledge insists it is ‘central to the story of salvation through Jesus Christ, and without this theme the Christian proclamation loses much of its power, becoming both theologically and ethically undernourished.’

Editing out blood sacrifice commits the very act is intended to avoid, violence.

It commits violence agains the text of scripture by eviscerating the language of the bible.

Scripture speaks of the blood of Christ 3 times more often than it speaks of the death of Christ. Such a statistic alone reveals the extent to which blood sacrifice is a dominant theme in extrapolating the meaning of Christ’s death. Scripture gives the witness repeatedly: God comes under God’s judgement as a blood sacrifice for sin. Put in the logic of the Old Testament’s sacrificial system: something of precious value is relinquished in exchange for something of even greater gain. Blood for peace.

We might find such language repellent. Many do. Perhaps we should recoil at it considering how its an indictment upon our own sinfulness. We might wish to alter the words we say when handing the host to a communicant. What we cannot do is pretend this is not the way scripture itself speaks. Not only is blood sacrifice a dominant motif in scripture, Fleming Rutledge demonstrates how its a theme upon which many other atonement motifs rely, such as representation, substitution, propitiation, vicarious suffering, and exchange. Something as simple as switching from ‘The blood of Christ shed for you’ to ‘The cup of love’ effectively mutes the polyvalence of scripture’s voice.

And what does lie behind our resistance to blood sacrifice?

Reading The Crucifixion, I can’t help but wonder if the popular disdain for blood sacrifice owes less to our concern for the violence of the century past (and the ways our theological language underwrote it) and if it has more to do with the way that the worldview of blood sacrifice contradicts our contemporary gospel of inclusivity along with its charitable appraisal of human nature and its ever progressing evolution. The self-image we derive from American culture is that I’m okay and you’re okay. We translate grace according to culture so that Paul’s message of rectification becomes ‘accept that you are accepted.’ God loves you just as you are, we preach, Because of course, God loves us. How could a good God not love wonderful people like us? As Stanley Hauerwas jokes, we make the doctrine of the incarnation ‘God put on our humanity and declared ‘Isn’t this nice?!’

The governing assumption behind blood sacrifice could not be more divergent. ‘The basic presupposition here [in Leviticus],’ says Rutledge, ‘is that we aren’t acceptable before the Lord just the way we are. Something has to transpire before we are counted as acceptable…the gap between the holiness of God and the sinfulness of human beings is assumed to be so great that the sacrificial offering has to be made on a regular basis.’ The self-satisfied smile we see in Joel Osteen is a reflection of our own.

Our glib view of ourselves is such that we cannot imagine why God would not want to come near us.

Scripture’s sober view of us is that we cannot come near God, in our guilt, without God providing the means for us to live in God’s presence.

Another life in place of our own, a blameless and unblemished one.

Whatever our reason for spurning blood sacrifice, our disdain for it raises an even more pernicious problem, for, as Fleming Rutledge implies, if we refuse to interpret Christ’s death as a blood sacrifice, ruling such imagery as out of bounds, what connection remains between Jesus and Jesus’ own scriptures? To jettison blood sacrifice is to unmoor Jesus from the bible by which he would have understood his own deeds and death, making it unclear in what sense it makes any sense to say, as we must, that Jesus was and is a Jew.

Disdain for blood sacrifice becomes a kind of supersessionism.

Desiring to cleanse our view of God of any violence we unwittingly commit a far worse sort of (theological) violence: cleansing God of God’s People.

Which begs the question, my own not Fleming’s, if progressive Christians in America today are substantively different than the Christian European sophisticates of the late 19th century who viewed the ethnic, cultic faith of the Jews with similar disdain.

If we profess the conviction that a crucified Jewish Messiah is Lord, then we must submit to understanding him according to the terms by which he would’ve understood himself.

And not only Jesus- the entire Book of Hebrews, which the Church Fathers understood as an extended sermon on Leviticus, is the longest sustained argument in scripture and the argument at hand is the preacher’s assertion that Christ’s death was a blood sacrifice offered for sin wherein priest and victim become one. At some point, no matter how squeamish the imagery might make the uninitiated, we must conclude that to do away with blood sacrifice requires us to do away with far too many of our sacred texts. Even Paul, as Rutledge unpacks, interpreted Jesus’ death as a sacrifice, doing so not in the cultic terms of the Book of Hebrews but in apocalyptic terms, as:

‘the definitive apocalyptic engagement with the forces of the enemy, at the frontier of the ages where Jesus’ self-abandonment was the ultimate weapon…the ultimate form of ‘passive resistance’ that overwhelms and routs the enemy.’

In addition to maintaining continuity between the testaments, the blood sacrifice motif also helps Christians avoid the common error of seeing Christ’s death as an occasion of God reacting to human sin and of God changing God’s mind about humanity as a consequence of Christ’s death. Instead, as Rutledge argues, the sacrifices of the Old Testament prepared the people for the perfect, once for all, sacrifice offered by Christ thus the cross is ‘an inherent, original movement within God’s very being. It is in the very being of God to offer God’s self sacrificially.’

Given her extended attention to blood sacrifice and to the scapegoat of the Levitical sacrifices, it surprised me that Rutledge largely confines the work of Rene Girard, whose scapegoat theory of the atonement is ascendant among progressives, to her footnotes. While she affirms Girard’s wisdom in identifying Christ’s death with the victimization of the lowly and oppressed, she wisely challenges how Girard’s emphasis on understanding Christ’s death purely in scapegoat terms has much to say to victims of oppression but has nothing to say for or about the oppressed’s victimizers.

Girard’s esteemed scapegoat theory is unable, Rutledge argues, to ‘envision the rectification of the [scapegoating’s] perpetrators.’

This little line buried in the footnotes made me long for an extended treatment of Girard, for her offhand critique hints at the way the blood sacrifice motif is inextricably linked to the offense of the Gospel:

‘For Christ also died for sins once for all, the righteous for the unrighteous.’

– 1 Peter 3.18

To unload the peculiar blood imagery of scripture, then, is to take on the prejudices of American culture, losing our particular, deeply offensive confession that God sacrificed God’s self not for the good and the godly, not for the righteous and the religious, but for the ungodly.

Sin does cost something.

It is right and good, I believe, to rejoice knowing Jesse Matthew will spend his life behind bars.

Nonetheless, the Gospel is that Christ died not just me or you or Pope Francis but for, serial killer and rapist, Jesse Matthew.

Trust me, I’ve seen the damage done by Jesse Matthew first hand.

I could so easily forget that Christ died for him too if, in my church, we didn’t weekly break bread and say ‘The blood of Christ poured out for you.’

For even him.