The final substantive section of Gary N. Fugle’s book Laying Down Arms to Heal the Creation-Evolution Divide looks at the regions of (apparent) conflict between evolutionary biology and the Christian Bible. His approach is predicated on the assumption that “we cannot comfortably argue that God created one reliable source of information in the Bible and created a second conflicting, unreliable source in nature.” And he goes on: “This means we should use Scripture to rightly interpret what we observe and experience in nature and, at the same time, allow the natural world to inform us how to rightly interpret the Bible.” (p. 225) He is convinced that “the bible is inerrant in what God intended to communicate.” (p. 228) But this doesn’t mean that human interpretations are inerrant. In the post on Tuesday Reading the Bible With Evolution in Mind we looked at his discussion of creation in six days and the biblical flood. Today we will turn to the question of human evolution and its impact on our reading of Genesis 2-3.

The final substantive section of Gary N. Fugle’s book Laying Down Arms to Heal the Creation-Evolution Divide looks at the regions of (apparent) conflict between evolutionary biology and the Christian Bible. His approach is predicated on the assumption that “we cannot comfortably argue that God created one reliable source of information in the Bible and created a second conflicting, unreliable source in nature.” And he goes on: “This means we should use Scripture to rightly interpret what we observe and experience in nature and, at the same time, allow the natural world to inform us how to rightly interpret the Bible.” (p. 225) He is convinced that “the bible is inerrant in what God intended to communicate.” (p. 228) But this doesn’t mean that human interpretations are inerrant. In the post on Tuesday Reading the Bible With Evolution in Mind we looked at his discussion of creation in six days and the biblical flood. Today we will turn to the question of human evolution and its impact on our reading of Genesis 2-3.

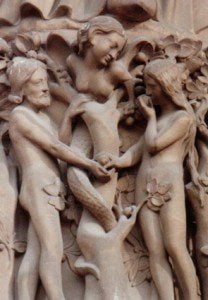

Adam, Eve, and Original Sin. This is the tough one for most Christians. There are two related questions.

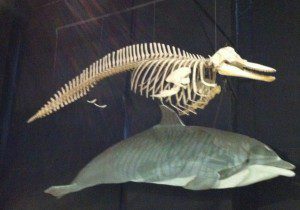

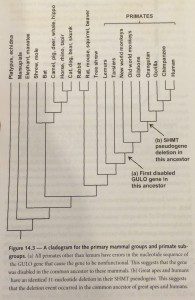

First, in what way are humans distinct from other animals? Is it through a distinct special creation? The DNA and fossil evidence suggests not. To answer this question Fugle first considers the meaning of “image of God” as used in Genesis 1:26-27. He sees this as a combination of characteristics and calling. “We are made like God in the ability to reason and understand and form a spiritual relationship with our Creator.” (p. 250) and “with these characteristics, humans are distinctly created to be God’s representatives on earth,as stewards over the rest of creation.” (p. 250) Next Fugle considers Adam and Eve. One view holds that Genesis 2-3 is a meaningful metaphorical account describing who and what humans are. This view is consistent with Christian orthodoxy and shouldn’t simply be dismissed out of hand. However, it is not the view that Fugle prefers. He prefers the option that suggests “that Adam was singly taken aside by God from physically evolved humans and the image of God was divinely imparted to him.” (p. 252) The divinely bestowed image was passed on to his offspring. This view has problems of its own, primarily that the DNA evidence does not support descent from a single pair as Fugle acknowledges. Overall Fugle’s reading values the contributions made by Derek Kidner (Genesis), C. John Collins (Genesis 1-4) and Denis Alexander (Creation or Evolution).

Second, what about the entrance of sin? Fugle hangs onto the idea of a unique couple because he finds the entrance of sin and death through Adam to be a foundational part of Paul’s teaching in Romans 5 and 1 Corinthians 15. This doesn’t mean that all death entered with Adam’s sin. The tree of life in the garden is ample reason to believe that Adam and Eve were mortal apart from the divine gift of God. Other animals were also mortal. However, in Romans 5 and 1 Corinthians 15 “Paul is unquestionably referring to Adam and his actions as if they are a historical reality on par with the reality of Jesus.” (p. 255) In his view the connection Paul is making between a singular real Adam and Jesus is broken if Adam is symbolic. More than this it would make us wonder about Paul’s inspired authority.

It is one thing for Paul to have inaccurate perceptions about natural science that are not corrected in Scripture, but it is something else for him to be wrong or figurative about real world descriptions that are so central to his theology. If Paul is wrong or loose with the historical reality of Adam, is he credible in his interpretation of events in his own time or how he saw Jesus in other passages of the Old Testament? (p. 255)

Paul often refers back to the Old Testament as he describes Jesus as God’s Messiah. Fugle asks:

But if Paul is wrong or purposely artistic about Adam, isn’t he just as likely to be inaccurate or unclear in his other insights? The profound implication is that this challenges the inspired nature of Scripture and its authority. (p. 256)

In addition to the implications for the trustworthiness of Paul and the authority of Scripture, Fugle also finds a historical Fall as significant for the core biblical themes of redemption and restoration.

Redemption and restoration are terms that primarily mean a return to a state that once existed but was lost. Importantly, they do not typically mean improvement or correction from an inherent negative condition that was always present. Paul’s message (and the message throughout Scripture) makes most sense if Jesus redeems us to a condition once experienced in Adam. This fundamental Christian proclamation is muddled if human sinfulness has always been an aspect of human nature. (p. 256)

But is Adam really so central to Paul’s thinking?

I have a number of comments on this section.

First, centrality of Adam. If Paul’s reference to Adam is central to his theology and thus to our understanding of Christ and God’s work in the world, then Fugle’s position and conclusions are reasonable. They are consistent with mainstream science and with Christian orthodoxy. Many Christian scientists I know hold to variants of this position. I will never rule this out as a viable alternative. In fact, I think that some kind of Fall is historical reality, although not necessarily of a unique couple. The Fall is historical reality along the same lines that the idea of creation by God in the beginning is historical reality. However, I am not convinced that Adam is central to Paul’s theology. Adam may be invoked for illustrative purposes. And this leads to the second point.

First, centrality of Adam. If Paul’s reference to Adam is central to his theology and thus to our understanding of Christ and God’s work in the world, then Fugle’s position and conclusions are reasonable. They are consistent with mainstream science and with Christian orthodoxy. Many Christian scientists I know hold to variants of this position. I will never rule this out as a viable alternative. In fact, I think that some kind of Fall is historical reality, although not necessarily of a unique couple. The Fall is historical reality along the same lines that the idea of creation by God in the beginning is historical reality. However, I am not convinced that Adam is central to Paul’s theology. Adam may be invoked for illustrative purposes. And this leads to the second point.

Second, artistry in illustration. I don’t see why Paul could not be purposely artistic about the Adam. It seems obvious that he was purposely artistic about Abraham’s seed in Galatians 3:16:

The promises were spoken to Abraham and to his seed. Scripture does not say “and to seeds,” meaning many people, but “and to your seed,” meaning one person, who is Christ.

Paul is using a promise to Abraham about his son, grandsons, great grandsons … to make a point about Jesus and about gentiles. He is using the passages in Genesis in a way that they were not originally intended and in a way that they are not generally read today. Paul’s point in Romans 5 and 1 Corinthians 15 is Jesus, not Adam and in Galatians 3 it is Jesus, not Abraham’s seed. In other words, Paul may be using Scripture in a manner consistent with his Jewish culture to make a point about Jesus. This is a point his audience would understand.

Third, Paul’s limits. Paul could have mistakenly believed that Adam was historical and used the passage of Scripture to make a point about Jesus. The specific point he was making may rest on the received story of Genesis 3 rather than an ontological fact. No one has convincingly explained to me how this would undercut Paul’s inspiration concerning the message he was preaching from God concerning Jesus. Fugle suggests that if Paul was in error or used Adam artistically it undermines the authority of Scripture and “tends to reduce the bible to a human-constructed book containing inaccurate connections and/or poetic manipulations that are difficult to decipher.” (p. 256) This is an issue that deserves consideration at greater depth. However, it seems to me that the major issue isn’t really Paul’s use of Scripture but the origin of sin. And this leads to the fourth point.

Fourth, redemption from a singular act. If creation, fall, redemption is the central theme of Scripture then a singular fall clearly defined in time may well be of central theological importance. This is a topic for discussion. Although creation, fall, redemption, new creation is a common casting of the biblical story it is not entirely clear to me that this is the best way to frame the sweep of scripture. I am not convinced that the Bible is structured as a logical argument – introduction, problem, solution, conclusion. Rather the Bible is the story of God’s relationship with his creatures.

Over the last several years I have spent most of my commutes listening to Scripture read or performed in order to be immersed in and formed by the story of God’s work in the world. (Far better than spending the time immersed in talk radio (HT T)). I have also chosen to read and review a number of books on Old Testament theology in order to dig deeper into topics that are not often raised in church (Iain Provan’s Seriously Dangerous Religion, Walter Moberly’s Old Testament Theology, Richard Middleton’s The Liberating Image, and John Walton and Tremper Longman’s NIVAC and Baker commentaries on Job are examples of this focus – but don’t hold any of these people responsible for my views) .

Some things seem clear in the sweep of Scripture.

- God is Sovereign, and this includes God as Creator.

- Humans are fallen and have been fallen for all of remembered history.

- The major theme of the story is the faithfulness of God. God is faithful, though humans are not. We see this faithfulness from Genesis 1 through Revelation, but it is especially the connecting theme from Genesis 3 through Acts.

- God has made known his law. “And what does the Lord require of you? To act justly and to love mercy and to walk humbly with your God.“

- Jesus actions recorded in the Gospel’s are framed in terms of his identity as God’s Messiah. (The Prophets are essential for understanding this.)

- Paul (and others) bring to the Old Testament story the new realization that God’s faithfulness involved incarnation.

- Jesus is the faithful human (the faithful Israelite, the faithful seed of Abraham)

- Jesus is the answer to the promise of an eternal Davidic Dynasty

- The Son is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn over all creation.

- In the beginning was the Word … and the Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us.

The high Christology of the New Testament is significant. God himself did what humans not only did not do but could not do. I am not convinced that our inability was the result of Adam’s sin. Somehow it is part of being mortal – not God – in the context of God’s creation.

- God’s plan for the ultimate future is something we cannot really begin to fathom. It will be something different, where night and sea (chaos) and human sin are no longer part of the picture. Our science, based on this world, cannot get us from here to there.

Redemption from the singular sin of Adam does not seem an emphasis in the sweep of scripture. Perhaps our errant human interpretation of Paul in Romans 5 and 1 Cor. 15 and of Genesis 3 has made the singular act of Adam and Eve so important. One drawback of this interpretation is that it seems to make the incarnation a response, rather than part of God’s plan from the beginning. I don’t think that this is consistent with the relationship between creation and Christ found in John 1 and Colossians 1.

God is not the author of evil. Some suggest that the singular sin of Adam and Eve is required to save God from being the author of sin and evil. However, it seems to me that it is really the bestowal of genuine creaturely freedom that saves God from this charge. This freedom could have come in any way at any time. The important fact is that given freedom we fell individually and as a species. I tend to agree with C.S. Lewis’s description in The Problem of Pain, CH 5 “The Fall of Man.”

For long centuries, God perfected the animal form which was to become the vehicle of humanity and the image of Himself. He gave it hands whose thumbs could be applied to each of the fingers, and jaws and teeth and throat capable of articulation, and a brain sufficiently complex to execute all of the material motions whereby rational thought is incarnated. The creature may have existed in this stage for ages before it became man: it may have even been clever enough to make things which a clever archaeologist would accept as proof of its humanity. But it was only an animal because all its physical and psychical processes where directed to purely material and natural ends. Then in fullness of time, God caused to descend upon this organism, both on its psychology and physiology, a new kind of consciousness which could say “I” and “me,” which could look upon itself as an object, which knew God, which could make judgments of truth, beauty, and goodness, and which was so far above time that is could perceive time flowing past. … We do not know how many of these creatures God made, nor how long they continued in the Paradisal state. But sooner or later they fell. Someone or something whispered that they could become as gods. … They wanted some corner in the universe in which they could say to God, “This is our business, not yours.” But there is no such corner. They wanted to be nouns, but they were and must eternally be, mere adjectives. We have no idea what particular act, or series of acts, the self-contradictory, impossible wish found expression. For all I can see, it might have concerned the literal eating of a fruit, but the question is of no consequence.

God could have created humans any way he chose. It makes little sense to sit in judgment on his choice. All we can really do is go with the evidence. And the evidence seems clear: God created humans through evolutionary processes. The process probably involved a population no smaller than some thousands. Like Fugle (although I don’t quite agree with all of his conclusions and I am sure that he doesn’t agree with all of mine) I think that we should use Scripture to rightly interpret what we observe and experience in nature and, at the same time, allow the natural world to inform us how to rightly interpret the Bible.

All in all Fugle’s book is an excellent resource on the interaction of evolutionary biology with Christian faith. It will open the door for many important discussions. His commitment to Christian faith, his honesty with the scientific evidence, and his clear readable style make it a book well worth reading.

And let’s resume a discussion. I am open to being convinced that a unique Adam and Eve and a singular well defined act of rebellion are essential for redemption through Christ to be meaningful. As Fugle and others (Tim Keller, Derek Kidner, Denis Alexander, Jack Collins, Henri Blocher, John Stott, for example) have shown, there are ways to reconcile human evolution with such a view.

Is Adam central to Christian theology?

Is the Biblical story best framed as introduction, problem, solution, conclusion? (I.e. as creation, fall, redemption, new creation)

If you wish to contact me directly, you may do so at rjs4mail[at]att.net

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.