The industrious ants store up food for the winter while the grasshopper sings the days away. Aesop’s fable of The Grasshopper and the Ants provides an ancient example of moral lessons derived from nature. Ants are always working and foraging for food. We would do well to emulate this industry. But can nature alone really provide moral lessons? Is it wise to seek such lessons in nature?

The industrious ants store up food for the winter while the grasshopper sings the days away. Aesop’s fable of The Grasshopper and the Ants provides an ancient example of moral lessons derived from nature. Ants are always working and foraging for food. We would do well to emulate this industry. But can nature alone really provide moral lessons? Is it wise to seek such lessons in nature?

Although ants may provide a positive lesson, what about wasps? Charles Darwin commented in a letter to Asa Gray:

There seems to me too much misery in the world. I cannot persuade myself that a beneficent & omnipotent God would have designedly created the Ichneumonidæ with the express intention of their feeding within the living bodies of caterpillars, or that a cat should play with mice.

When we expect moral lessons from nature, nature will often disappoint … 0r take us in a direction that seems abhorrent.

And this brings us to the last post on Stephen Jay Gould’s book Rocks of Ages: Science and Religion in the Fullness of Life. The final section of the book looks at psychological reasons for the conflict between science and religion. Under Gould’s principle of NOMA (nonoverlapping magisteria) there is no reason for conflict between science and religion (as Gould defines religion), yet conflict remains a popular view. The search for moral and meaning in nature plays an important role here.

Gould sees his proposal of NOMA differentiating …

… between two components of wisdom in a full human life: our drive to understand the factual character of nature (the magisterium of science), and our need to define meaning in our lives and a moral basis for our actions (the magisterium of science). (p. 175)

In his view science – the study of nature – is amoral. It provides information that may inform our moral choices but it is intrinsically neutral. Moral choices must be founded on something other than science. But this has profound consequences for faith as well.

Humans are nothing special. Nature is without meaning and any attempt to attach any particular significance to the species Homo sapiens is misguided. The universe just is, the earth just is, we just are.

We long to situate ourselves on a benevolent, warm, furry, encompassing planet, created to provide our material needs, and constructed for our domination and delectation. Unfortunately, this pipe dream of succor from the realm of meaning (and therefore under the magisterium of religion) imposes definite and unrealistic demands upon the factual construction of nature (under the magisterium of science). (p. 177)

The billions of years of life predating the appearance of humans, in Gould’s view, negates the possibility that there could be any profound ‘natural’ (or divine) meaning and purpose for humans. He finds Psalm 8 a passage that defines the mistaken view of human importance. Humans are insignificantly unimportant in the universe, the result of a fortunate (for us) set of contingent events on minor speck of rock in an immense universe. The view of nature that Darwin and Darwin’s theory of evolution opened up, again in Gould’s view, follows a logical procession. God does not will the death or deformity of a single child. Events are best viewed as chance occurrences. God (if there is a God) allows a freedom in nature. But on a larger scale what is Homo sapiens? Gould develops his argument using a letter that Charles Darwin wrote to Asa Gray.

Darwin, who has been setting Gray up for this denouement all along, now moves in for the kill. If a single baby is only an individual in a population of human beings, why should a single species rank as more than an individual among all earthly species in the fullness of geological time? And why should Homo sapiens be viewed as a goal and a generality, when Pharkidonotus pericarinatus (a favorite fossil snail of mine – I am not making this name up), which lived for a much longer time with markedly larger populations, ranks as only a particular accident of history? What, beyond our dangerous and unjustified arrogance, could even permit us to contemplate such a preferred status for one species among the millions that have graced the history of our planet? (p. 202)

This is the cold bath of reality, into which Gould feels we must jump. Humans are not special and like other species on earth, past, present, and future, are particular accidents of history.

No moral lessons. Gould also argues that the world is not a warm and fuzzy place. There is no profound meaning in anything and it is unwise to search for meaning. The beauty of a mountain, the industry of ants, the maternal or ‘playful’ behavior of cats, the provision of food for a lion, the behavior of ichneumonid wasps, all of these just are. No moral message should be drawn. Charles Darwin and Mark Twain (both of whom he quotes) have …

No moral lessons. Gould also argues that the world is not a warm and fuzzy place. There is no profound meaning in anything and it is unwise to search for meaning. The beauty of a mountain, the industry of ants, the maternal or ‘playful’ behavior of cats, the provision of food for a lion, the behavior of ichneumonid wasps, all of these just are. No moral message should be drawn. Charles Darwin and Mark Twain (both of whom he quotes) have …

…rang the death knell over “all things bright and beautiful” – indeed, over any false argument that seeks the basis of moral truth (or any other concept under the magisterium of religion, including the nature and attributes of God) in the factual construction of the natural world. NOMA demands separation between nature’s factuality and humankind’s morality – dare I say that never the Twain shall meet? (p. 189)

Gould is convinced that everything science has taught us points to an amoral purposeless universe that “just is”. Nature is constructed without reference to such abstract human concepts. He sees the importance of his proposition of NOMA in the way it separates moral and scientific discussions. There may be psychological comfort in a religious view of nature with purpose and meaning. There may be psychological comfort in a naturalist view that derives moral instruction from the realities of nature … such as survival of the fittest and heroic dolphins. But both are errant. We need to struggle for moral meaning.

What can be more deluding, or even dangerous, than false comfort that blinds our vision and inspires passivity? If moral truth lies “out there” in nature, then we need not struggle with our own confusions, or with the varying views of fellow humans in our diverse world. We can adopt the much more passive approach of observing nature (or just accepting what “experts” tell us about factual reality) and then aping her ways. But if NOMA holds,and nature remains neutral (while bursting with relevant information to spice up our moral debates), then we cannot avoid the much harder, but ultimately liberating, task of looking into the hearts of our distinctive selves. (p. 204)

While some may see Gould’s view, especially the utter insignificance of humans, as depressing, Gould himself viewed it as exhilarating and liberating. “We are the offspring of history, and must establish our own paths in this most diverse and interesting of conceivable universes – one indifferent to our suffering, and therefore offering us maximal freedom to thrive, or to fail, in our chosen way.” (p. 207)

Final comments. Gould’s view of NOMA involves a total separation of scientific reasoning and moral reasoning. Yes, science provides information that can help inform moral reasoning, but it provides no sure foundation for moral conclusions. Here he speaks primarily to scientists … nature is amoral. This is an important point.

Gould also sees efforts like those funded by the Templeton Foundation to seek a synthesis of science and faith as unfortunate. We would be better to give up on the misguided attempt to hold onto the past and move with boldness into the (godless, or perhaps deist) future. Although he died before BioLogos was formed, I expect that he would view this as just one more irrational attempt to hold onto the past (the orthodoxy of Christian faith). Gould’s vision of NOMA leaves no place for the reality of Christian faith.

A universe with purpose and meaning? … No!

A personal God who intervenes in history and relates with humans created in His image? … No way!

The Word who became flesh and dwelt among us? Gould ends his book with a reference to John 1:1 – but only because language (word) makes us human. The idea of an incarnation, “Christ Jesus who being in very nature God … being made in human likeness … becoming obedient to death – even death on a cross” is utterly ridiculous (and a clear violation of NOMA).

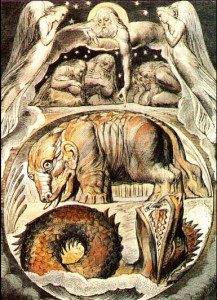

Yet Gould’s book has been well worth reading and wrestling with. I find a great deal of value and insight in the way Gould divorces “nature” and morality. For every positive lesson, such as that provided by the industrious ant, we can find a somewhat repulsive example – the ichnuemon wasps. The world is created as it is, with parasitic wasps, carnivores, and cobras. We can admire the complexity of the world without trying to find deep moral or theological significance in every bit. Even as Christians we must sit with Job and realize that there is much we do not know and understand about God’s creation and we had best shut up. Most (all?) attempts to speculate theologically on the reason for the creation of ichneumon wasps, for example, are justly ridiculed. (Image from Blake’s illustrations of Job.)

Yet Gould’s book has been well worth reading and wrestling with. I find a great deal of value and insight in the way Gould divorces “nature” and morality. For every positive lesson, such as that provided by the industrious ant, we can find a somewhat repulsive example – the ichnuemon wasps. The world is created as it is, with parasitic wasps, carnivores, and cobras. We can admire the complexity of the world without trying to find deep moral or theological significance in every bit. Even as Christians we must sit with Job and realize that there is much we do not know and understand about God’s creation and we had best shut up. Most (all?) attempts to speculate theologically on the reason for the creation of ichneumon wasps, for example, are justly ridiculed. (Image from Blake’s illustrations of Job.)

More importantly, I agree with Gould that science is simply an investigation of nature. As a Christian I believe that this is an investigation of God’s creation, but this doesn’t affect the practice of science itself. It only affects the interpretation I attach, an interpretation quite different from the meaningless, purposeless view of Gould. It is important, however, to learn to distinguish science from the metaphysical baggage attached to it from all sides.

And this is a good place to stop and start a conversation once again.

Do you see any value in Gould’s proposal of NOMA?

How would you counter his arguments about the utter insignificance of humans?

Does nature hold moral lessons to guide our thinking?

If you wish to contact me directly you may do so at rjs4mail [at] att.net.

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.

What ideas were presented to you about heaven when you grew up? [Please drop a comment because I’d like to know how many of us grew up with the notions of a new heaven and new earth — let’s call it a renewed earth heaven — or a heaven up there and out there — let’s call it a spiritual heaven.]

What ideas were presented to you about heaven when you grew up? [Please drop a comment because I’d like to know how many of us grew up with the notions of a new heaven and new earth — let’s call it a renewed earth heaven — or a heaven up there and out there — let’s call it a spiritual heaven.]