By Jameelah Rheaves, one of our Northern students. At times a paper for a class comes across my desk that I say, “This has to be shared with a wider public, beginning with my blog.” Jameelah’s review of Vashti McKenzie’s book was such a paper — the paper was fresh, insightful, and eye-opening for all those who (like me) don’t know the African American woman-in-the-church well enough.

By Jameelah Rheaves, one of our Northern students. At times a paper for a class comes across my desk that I say, “This has to be shared with a wider public, beginning with my blog.” Jameelah’s review of Vashti McKenzie’s book was such a paper — the paper was fresh, insightful, and eye-opening for all those who (like me) don’t know the African American woman-in-the-church well enough.

Once in our class this winter on women, the church and ministry, I said in candor that I don’t believe the African American church is part of American evangelicalism, and I believe that. American evangelicalism is a white church movement that at times (and only at times) includes African Americans. Especially when it wants to look inclusive. But dig into the back rooms where decisions are made and where cultures are formed and you discover that, no matter how hard some white leaders try, the culture formed is a white evangelical culture. Read Korie Edwards, The Elusive Dream, if you want to see a deeper depiction.

I told the class that we need a good book on the history of women in the African American church. Pamela Cochran’s book on the history of evangelical feminism is almost entirely a story about white women … and we moved on with a hole in the syllabus. We do know the stories of some African American women, like Rebecca Protten or Mary McLeod Bethune, and the story about African American women in the church is chock-full of diversity, but the narrative of women in African American churches is a narrative largely untold. Tara Beth Leach sent me a link to Vashti McKenzie’s book, which I immediately passed on to Jameelah for her reading… and here we go, over to Jameelah in what follows.

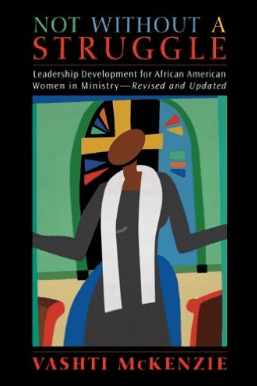

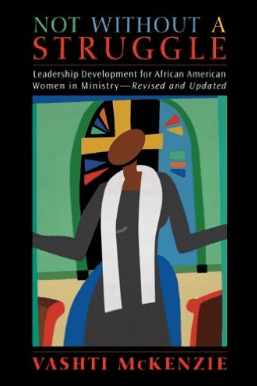

Vashti M. McKenzie,. Not Without a Struggle: Leadership Development for African American Women in Ministry. Pilgrim: Cleveland, 1996. Revised 2011 (Kindle Edition).

Vashti M. McKenzie is the first female Bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. She has served in various pastorates, including the chief pastor of the 18th Episcopal District in southeast Africa. She earned her Master of Divinity degree from Howard University Divinity School in 1985, and became a Doctor of Ministry from United Theological Seminary in Dayton, Ohio. She has hosted gospel radio programming, and gospel television segments called Evening Magazine. Other writings include, Strength in the Struggle: Leadership Development for Women, A Journey to the Well and Swapping Housewives.

This study examines the paradigm shift of women in leadership in the Church, whether it be Roman, Greek and African cultures or Eurocentric and African American denominations. But the book speaks especially to the African American woman who experiences the “double barreled shot-gun” of racism and sexism. McKenzie uses theological, Biblical and ancient data to objectively discuss both support and angst for women in leadership. She looks at the “shadow”[1] called sexism both in her experience and those of other women in ministry positions, and includes personal testimonies and letters of encouragement to women in ministry (two of which are men) — found in the epilogue. Her intent was to touch on issues, although not exhaustive, and to leave an “oral record for the “daughters of thunder” who will come behind me.”[2]

I do not believe I have ever read a more captivating preface alone. It placed a smile on my face because it was both relatable and inspiring. “Lift every voice” was the command, using the metaphor of music and the importance of the harmony as well as the lyric. McKenzie emphasizes that women in ministry have a certain “pitch” and “octave” that are unique and need to be heard. Within the first few pages I found myself reconsidering what I say my call is and what my call really is. I have a voice that needs to be heard.

Chapter one looks at historical perspectives of women in leadership from the Roman, Greek, and Jewish culture. McKenzie states women leaders emerge in the ancient world but it is difficult to retrieve sources that speak of them without a patriarchal bias. She then acknowledges the feminists and womanists of today, such as Virginia Mollenkott and Renita Weems, who attempt to bring a female perspective in the midst of the male perspective and she points at H. Wayne House.[3] She identifies this challenge: “… to bring forward and identify positive images of female leadership and at the same time destroy the myth of ‘otherness’: the assumption that women are peripheral and secondary historical objects of church and community life–the others.”[4] Being unbiased as one rediscovers the past is another challenge mentioned, that is, being able to bring women into the light as well as “discerning insights into oppressive systems”.[5] She gives strong and solid historical contexts and refers to exceptions as, “Yes, but…”

I appreciate the echo of “Yes, but” and believe it speaks to McKenzie’s research style and life as a black woman in leadership. In her historical outlines I appreciate her going beyond the canon and exploring apocryphal writings as well. I personally struggle with a council deciding what was inspired, and what wasn’t, and believe more cultural context can be missed if we never consider other writings.[6] For example, McKenzie mentions Thecla and Paul, and I sat for 45 seconds pondering who that was, before going to Google.

Chapter two explores women in the African culture, where we find women were more in partnership with their male counterparts; unlike Asia and Europe were women were viewed as inferior.[7] McKenzie writes:

The African woman was not silent, secluded or suppressed. African traditions in many areas appear to have developed a holistic approach to social organization, where both genders were vital participants, partners and peers… The African woman’s place was wherever her gifts would take her.[8]

It was the influence of a different culture and “civilization” that de-Africanized the structure of equality. McKenzie also touches on the denial of gender in order for one to fit into leadership roles, even in Christianity, by women cutting their hair, wearing male attire (Thecla) and/or maintaining their virginity or becoming celibate.[9]

In this chapter I again appreciate the detailed mention of Biblical women who aren’t necessarily named in the Bible, or are not spoken of in detail, such as Belkis/Makeda, Queen of Sheba and Queen of the South as mentioned by Jesus (Matt. 12:42; Luke 11:13). McKenzie also mentions queen Nefertiti and other women we learn about in the historical record. Her research is very rich.

Chapter three is on the “Historical Perspective on Female Leadership in the Church.” McKenzie begins stating, “The epitome of the ‘yes, but…’ tension in the historical perspective between the ideal silent and submissive patriarchal role of women and the individual achievements of the female leader is seen in the growth and development of the church in the United States.”[10] Women were stay at home wives and mothers; however, they were also leaders of churches and denominations despite the struggle and sometimes life threatening obstacles in front of them. In this chapter McKenzie discusses the greats such as Anne Hutchinson, Sarah Osborne, and Lucretia Mott. She also speaks of Antoinette Brown Blackwell who is “believed to have been the first woman ordained in this country.”[11]

In the Holiness/Pentecostal movements (my current church’s vein) women held leadership positions, such as the pastorate, and were influential writers for the church. McKenzie also details the lives of our “foremothers” from the 1800’s who were “preaching, seeking ordination, and planting churches” such as: Jarena Lee, a non-ordained AME preacher; Zilpha Elaw, a missionary; Rebecca Cox Johnson, a rejected AME minister who began the African American Shaker Community; Julia A. J. Foote, the first ordained deacon in the AMEZ(ion) Church; Amanda Berry Smith, a non-ordained AME turned Holiness preacher; and “an enslaved African named Elizabeth,” a Quaker minister.

McKenzie denoted when denominations began licensing and ordaining women and the skepticism and tolerance they endured. Concerns of a woman’s physiological health were at the forefront of concern (as if men never get sick) and how a church could function in a woman pastor’s absence for childbirth. McKenzie reports the same when a man had surgery — the associate minister would fill in. Another argument made by many against women leadership was other women were against it. McKenzie writes that if research is accurate “then a failure of women to bond may mean that women are their own worst enemies.”[12]

McKenzie in chapter three continues to highlight the African American Church as well as what we discover in Judaism. She also highlights denominations in the American Church that still refuse to license or ordain women: The Catholic Church, where one Kentucky Bishop faces expulsion for allowing women priests, the Church of God in Christ, and the Southern Baptist Convention, which is slowly transitioning.

Chapter four begins by looking at varying perspectives of theology, with McKenzie making clear the universal perspective of “Barth’s minimizing experience and elevating the Word of God alone”[13] and that it “is not universal.” Unfortunately looking at the dominant culture’s (Eurocentric’s) perspective robs the voice of the Church as it is not inclusive of all, hence the development of feminist and liberation theology. McKenzie introduces the Womanist perspective, coined by Alice Walker, with the Bible as their authority, a perspective that describes the African American woman’s perspective. She states:

It speaks of surviving in the struggle of being in charge, courageous, assertive and bodacious. It speaks of being fully grown and responsible enough to contemplate and dialog theologically independent of other races and gender.[14]

Objections to women in leadership include the New Testament’s “house-codes,” some non-canonical writings, as well as the Didascalia Apostolorum and Apostolic Church Order indicating Jesus never appointed women beyond discipleship. There are also issues with women being celebrants.[15] McKenzie cites Henry Van Dyke who was an opponent to “visible” female leadership roles. Support for his stance comes from 1 Timothy 2:11. She opposes this argument using historical references of women in leadership such as Thecla, who Paula and Marcina looked to for leadership. She claims such third and fourth century thinking that has carried into this century is from power and control.[16] She poses the great question of “would the Holy Spirit give a gift in vain?” if it was truly God’s intent for only men to be in leadership.[17]

In support of women in leadership, McKenzie describes different types of feminism: “liberal” which looks at equality between men and women; “Marxist” which is concerned with economic equality; “romantic” which looks at promoting emotional and natural aspects[18] and finally “biblical” which is an apologetic to scriptural references[19]. McKenzie believes women in leadership draw support from Jesus and experiences of Christian women.[20]

Also in this chapter McKenzie looks at the challenges for a theology of “many” that includes formulating a constructive theology that includes the African American community and considers the meaning of Christ based on class, but that also needs to explore oppressive symbolism in the Bible (which Weems addresses in her book). Again, McKenzie gives unbiased descriptions which are hard to challenge.

One descriptor that can be challenged is in chapter five when McKenzie differentiates prophetess and prophet stating the terms have gender differentiation. Instead of challenging the interpretations, McKenzie accepts some Old Testament translations of prophetess for woman.[21] The same lack of challenge applies for deacon/deaconess, when describing Phoebe.[22] This was surprising, in that there are no gender differentiations. Woman, too, is prophet and/or deacon.

Another surprise was in McKenzie’s description of leadership. While Biblical, it was a corporate view, which is standard in some writings; however, she detailed differences in male and female leadership styles, which were both generalization and somewhat stereotypical, and there was no caveat that said “research suggests.”[23]

Next, while there is mention of growth and building other leaders, there is no actual description of discipleship, which I believe is an important task of a leader. She also touches on lack of mentorship for women, and compares America’s Eurocentric view of leadership in comparison to Libera’s experience. While another perspective is extremely valuable, to take one African country (which has also been influenced by Europe) instead of several cross continental perspectives was lacking.

Chapter seven touches on leadership styles and styles from the Womanist perspective which include, Sister Girlfriend, The Queen, Mama, Wise Woman (also known as Zoe in African culture), Sapphhire (from Amos and Andy), Finessa, Liberationist, Africentric, Chameleon, and Street Fighter. Finessa is a descriptor of a leader who can put the “F” in finesse and lead her congregation with a soft, silent, strength (reminds me of my fellow student, Tara Beth Leach). Chameleon is described as one who adjust to their environment, and is comfortable around a variety of ethnic groups—“when in Rome…” While I cannot adapt to various cultures through language (as described) this style resonated most with me, as I have worked in various ministries and in various cultures; however, I have a touch of all styles, except possibly “Street Fighter,” who is independent, and leads based on their survival skills.

In chapter nine, McKenzie list her ten commandments for women leaders, as well as the Womanist Ten Commandments. A commandment that resonated with me was McKenzie’s number eight, Thou Shall Pursue Continuing Education and Personal Development in Order to Provide Quality Leadership. I once had a conversation with my home pastor (who was like my Grandfather) about why he never taught on spiritual warfare, to which he replied “these people don’t believe in spirits!” I later asked my former pastor the same and he replied it wasn’t his specialty. I believe it is our responsibility as leaders to be knowledgeable about the Bible and able to teach and explain concepts beyond the typical sermons on Fruit of the Spirit and Sin. It is our duty to continue to grow and develop as people and ministers, for the sake of God’s people, and for His glory.

Lastly, in chapter ten McKenzie looks at where we go from here with the information we have. She states the (African American) Church is battling sexism and the challenge is to include “gender specific and gender inclusive learning experiences” by examining ancient writings, strengthening leadership skills, embracing Biblical egalitarianism without “eroding male/female relationships, and sharing the information on a larger scale through retreats and conferences where idea sharing can take place (129-30). The Epilogue does some of what McKenzie recommends by encouraging women leaders, through various letters written by African American women in top leadership positions.

In conclusion, a quote that gave me a flashback to my childhood was:

…women are allowed to carry, even read from the Bible, but not preach from it; clean and decorate the pulpit but not sit in it; raise money for the church, but not participate in the decision of how it is spent; or be pretty in the pew rather than intelligent in the boardroom.[24]

I struggled with the idea of women being in leadership roles such as deacon, and preacher, well into college. It wasn’t until I attended an American Baptist Church (previously NBC) that I ever saw a woman deacon and heard a woman minister who was not an “evangelist.” Women were in the kitchen or assisting male leaders, unless teaching. I am blessed to be in a church now (non-denominational with apostolic doctrine) that allows women to function in whatever God has called them to, both equipping and mentoring. An area that is lacking is telling the stories of women. This lacks in many churches and even in media. I recently saw a t-shirt promoting “#squadgoals,” and listed were the typical, Ruth, Sarah, Mary and Esther. If one didn’t read the Bible, you would assume those are the only real women in power in the Bible, no matter what church one attends. We must “lift every voice” and tell every story and strive to get to back to the truth of women in the Bible and women in various cultures. This can be through preaching series, small group curriculum, Bible studies, and so on. We must be willing to read the Bible and research context, and not start in the middle of passages, missing the point. Finally, we must discern what God originally intended for humanity, and not what culture deems appropriate. Then the Church Acts! We counter-narrate. This can be, however, as the title suggest, “Not without a Struggle.” Lord, let it be!

[1]McKenzie, xv.

[2] Ibid., xxii.

[3] Ibid., 1.

[4] Ibid., 3.

[5] Ibid.

[6] I’d never even heard of the Apocrypha until 2012, and have not yet completed it.

[7] Ibid., 13.

[8] Ibid., 14-15.

[9] Ibid., 16.

[10] Ibid., 23.

[11] Ibid., 27.

[12] While I have not personally experienced this (to my knowledge) many women even at Northern report combating jealousy, or competition among other women. A few women at Northern have developed a fellowship, Black Female Fellowship, and I can say, this stereotype has been broken, at least on this campus! Hallelujah!

[13] Ibid., 47.

[14] Ibid., 53.

[15] Ibid., 49.

[16] Ibid., 51.

[17] Ibid., 52.

[18] Definitions by Anne Loades.

[19] View of Denise Lardner Carmody.

[20] McKenzie, 56.

[21] Ibid., 63.

[22] Ibid., 65.

[23] Ibid., 77.

[24] Ibid., 9.

Naomi Walters is an Associate Professor of Religion at Rochester College in Rochester Hills, MI, and in the final stage (read: defending this week) of the Doctor of Ministry program at Lipscomb University. Naomi enjoys reading Scripture with others, and imagining the kingdom of God described therein, a passion that informed her preaching ministry at the Stamford Church of Christ (CT) before beginning work at Rochester, where she now teaches courses such as Introduction to Preaching, Spiritual Formation, and Theology of Worship. She and her husband, Jamey, have two young children: Simon (Big Brother) and Ezra (Little Brother). When the kids let her, she enjoys reading, running, playing soccer, and watching TV.

Naomi Walters is an Associate Professor of Religion at Rochester College in Rochester Hills, MI, and in the final stage (read: defending this week) of the Doctor of Ministry program at Lipscomb University. Naomi enjoys reading Scripture with others, and imagining the kingdom of God described therein, a passion that informed her preaching ministry at the Stamford Church of Christ (CT) before beginning work at Rochester, where she now teaches courses such as Introduction to Preaching, Spiritual Formation, and Theology of Worship. She and her husband, Jamey, have two young children: Simon (Big Brother) and Ezra (Little Brother). When the kids let her, she enjoys reading, running, playing soccer, and watching TV. Though, of course, my preschool-aged self could not have articulated or explained my fascination with this book, I think it was the first time I realized, as the saying goes, that “there are always two sides to every story.” It was the first time I became aware of the role of a narrator in shaping the way a story is told. And I started asking questions: Was it really Goldilocks’ fault that the bears just left their house unlocked? Wouldn’t it have caused a lot of trouble for the rest of the village when Jack cut the beanstalk and a dead giant fell from the sky? Why would Hansel and Gretel go back home to the parents who abandoned them in the woods in the first place?

Though, of course, my preschool-aged self could not have articulated or explained my fascination with this book, I think it was the first time I realized, as the saying goes, that “there are always two sides to every story.” It was the first time I became aware of the role of a narrator in shaping the way a story is told. And I started asking questions: Was it really Goldilocks’ fault that the bears just left their house unlocked? Wouldn’t it have caused a lot of trouble for the rest of the village when Jack cut the beanstalk and a dead giant fell from the sky? Why would Hansel and Gretel go back home to the parents who abandoned them in the woods in the first place?