One of the most significant books in the last two decades is Richard Bauckham’s Jesus and the Eyewitnesses: The Gospels as Eyewitness Testimony [=JE], and a new second edition only reveals how significant the book is.

One of the most significant books in the last two decades is Richard Bauckham’s Jesus and the Eyewitnesses: The Gospels as Eyewitness Testimony [=JE], and a new second edition only reveals how significant the book is.

Speaking of eyewitness, when I was a PhD student at Nottingham, Jimmy Dunn and I drove together down to Cambridge for a Tyndale Lectureship. One of the lecturers was Richard Bauckham — of whom I had not heard but of whom Jimmy Dunn said he was an up and coming young scholar. Bauckham’s paper, or at least the bit I remember most (this was 1982), was that the destruction of Jerusalem was far less of a crisis for the early church than the death of apostles as eyewitnesses.

In 2006 the first edition of JE appeared and now a decade later he has updated and expanded that first edition. Reading the first edition is fine; but it is unwise to avoid all the new stuff in this second edition.

One issue that emerges from Bauckham’s book is how to classify this work: is it history or is it apologetics or is it both? Time and discussion will adjudicate this one. I will also wonder if testimony will ultimately satisfy the historians and historiographers. What he writes probably will not matter one bit to the apocalyptic crowd. Conservative evangelicals will trumpet the book but I suspect at times for the wrong reasons. But let’s begin this long series by looking at what I think is an introduction that pins his theses to the Historical Jesus Scholar’s Wittenberg Door.

He begins with observations about what is going on with the Historical Jesus Scholarship, and what he says here is so importantly accurate though many simply pass these nuances off as unimportant. They are (important) so mark his words (my italics):

From the beginning of the quest the whole enterprise of attempting to reconstruct the historical figure of Jesus in a way that is allegedly purely historical, free of the concerns of faith and dogma, has been highly problematic for Christian faith and theology.

Precisely: historical Jesus scholarship is out to reconstruct Jesus and to do so “free of the concerns of faith and dogma.” So, what is the historical Jesus? He delineates three possible meanings: the earthly Jesus, the canonical Jesus and the historical (or historian’s) Jesus:

What, after all, does the phrase “the historical Jesus” mean? It is a seriously ambiguous phrase, with at least three meanings. It could mean Jesus as he really was in his earthly life, in that sense distinguishing the earthly Jesus from the Jesus who, according to Christian faith, now lives and reigns exalted in heaven and will come to bring history to its end. In that sense the historical Jesus is by no means all of the Jesus Christians know and worship, but as a usage that distinguishes Jesus in his earthly life from the exalted Christ the phrase could be unproblematic.

However, the full reality of Jesus as he historically was is not, of course, accessible to us. The world itself could not contain the books that would be needed to record even all that was empirically observable about Jesus, as the closing verse of the Gospel of John puts it.

Now to the canonical Jesus:

We could therefore use the phrase “the historical Jesus” to mean, not all that Jesus was, but Jesus insofar as his historical reality is accessible to us. But here we reach the crucial methodological problem. For Christian faith this Jesus, the earthly Jesus as we can know him, is the Jesus of the canonical Gospels, Jesus as Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John recount and portray him.

And on to the historical Jesus (my italics throughout):

Yet everything changes when historians suspect that these texts may be hiding the real Jesus from us, at best because they give us the historical Jesus filtered through the spectacles of early Christian faith, at worst because much of what they tell us is a Jesus constructed by the needs and interests of various groups in the early church. Then that phrase “the historical Jesus” comes to mean, not the Jesus of the Gospels, but the allegedly real Jesus behind the Gospels, the Jesus the historian must reconstruct by subjecting the Gospels to ruthlessly objective (so it is claimed) scrutiny. It is essential to realize that this is not just treating the Gospels as historical evidence. It is the application of a methodological skepticism that must test every aspect of the evidence so that what the historian establishes is not believable because the Gospels tell us it is, but because the historian has independently verified it. The result of such work is inevitably not one historical Jesus, but many.

A Jesus apart from theology or meaning is impossible to find because there was no such person and no historian will provide us with one? Why?

All history — meaning all that historians write, all historiography — is an inextricable combination of fact and interpretation, the empirically observable and the intuited or constructed meaning. In the Gospels we have, of course, unambiguously such a combination, and it is this above all that motivates the quest for the Jesus one might find if one could leave aside all the meaning that inheres in each Gospel’s story of Jesus. One might, of course, acquire from a skeptical study of the Gospels a meager collection of extremely probable but mere facts that would be of very little interest. That Jesus was crucified may be indubitable but in itself it is of no more significance than the fact that undoubtedly so were thousands of others in his time. The historical Jesus of any of the scholars of the quest is no mere collection of facts, but a figure of significance. Why? If the enterprise is really about going back behind the Evangelists’ and the early church’s interpretation of Jesus, where does a different interpretation come from?

Bauckham is right in what follows in answer to that question:

It comes not merely from deconstructing the Gospels but also from reconstructing a Jesus who, as a portrayal of who Jesus really was, can rival the Jesus of the Gospels. We should be under no illusions that, however minimal a Jesus results from the quest, such a historical Jesus is no less a construction than the Jesus of each of the Gospels. Historical work, by its very nature, is always putting two and two together and making five — or twelve or seventeen.

He gets to the real issue: the historical Jesus scholar attempts to reconstruct an alternative Jesus. To what end?

From the perspective of Christian faith and theology we must ask whether the enterprise of reconstructing a historical Jesus behind the Gospels, as it has been pursued through all phases of the quest, can ever substitute for the Gospels themselves as a way of access to the reality of Jesus the man who lived in first-century Palestine.

Of course, there’s value in historical work, and I agree with this, but the issue again is To what end?

We need not question that historical study can be relevant to our understanding of Jesus in significant ways. What is in question is whether the reconstruction of a Jesus other than the Jesus of the Gospels, the attempt, in other words, to do all over again what the Evangelists did, though with different methods, critical historical methods, can ever provide the kind of access to the reality of Jesus that Christian faith and theology have always trusted we have in the Gospels. By comparison with the Gospels, any Jesus reconstructed by the quest cannot fail to be reductionist from the perspective of Christian faith and theology.

So Bauckham has a theory, a proposal, a counter, an alternative methodological angle:

I suggest that we need to recover the sense in which the Gospels are testimony! This does not mean that they are testimony rather than history. It means that the kind of historiography they are is testimony. An irreducible feature of testimony as a form of human utterance is that it asks to be trusted. This need not mean that it asks to be trusted uncritically, but it does mean that testimony should not be treated as credible only to the extent that it can be independently verified. There can be good reasons for trusting or distrusting a witness, but these are precisely reasons for trusting or distrusting. Trusting testimony is not an irrational act of faith that leaves critical rationality aside; it is, on the contrary, the rationally appropriate way of responding to authentic testimony. Gospels understood as testimony are the entirely appropriate means of access to the historical reality of Jesus.

We need to recognize that, historically speaking, testimony is a unique and uniquely valuable means of access to historical reality.

Testimony offers us, I wish to suggest, both a reputable historiographic category for reading the Gospels as history, and also a theological model for understanding the Gospels as the entirely appropriate means of access to the historical reality of Jesus.

OK, fine, this is valuable to the core. But the issue is how reliable is that testimony? Can we ever escape the historian’s question and the historian’s end? In other words, what if one concludes the testimony is not reliable on something minor (did Peter find a coin in the fish’s mouth?) or on something major (did Jesus do the miracles?) or something that interprets the actions for us (did Jesus say I am the Way or not? Did he solicit a Messianic confession or not? Did Jesus speaks of the cross as saving or not?)? Does testimony escape reliability? These are my questions as I read Bauckham with you.

In general, I shall be arguing in this book that the Gospel texts are much closer to the form in which the eyewitnesses told their stories or passed on their traditions than is commonly envisaged in current scholarship. This is what gives the Gospels their character as testimony.

Part of my intention in this book is to present evidence, much of it not hitherto noticed at all, that makes the “personal link of the Jesus tradition with particular tradents,” throughout the period of the transmission of the tradition down to the writing of the Gospels, if not “historically undeniable,” then at least historically very probable.

If, as I shall argue in this book, the period between the “historical” Jesus and the Gospels was actually spanned, not by anonymous community transmission, but by the continuing presence and testimony of the eyewitnesses, who remained the authoritative sources of their traditions until their deaths, then the usual ways of thinking of oral tradition are not appropriate at all.

Oral testimony was preferable to written sources, and witnesses who could contribute the insider perspective only available from those who had participated in the events were preferred to detached observers.

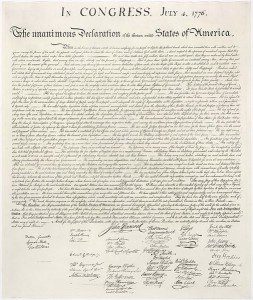

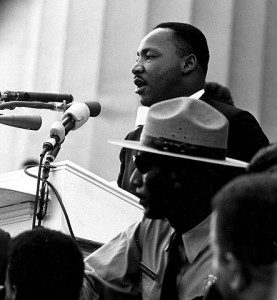

The second case study comes from Martin Luther King Jr. His argument for desegregation wasn’t based on a rational argument. It was based on a deeply moral argument. Human rights are only inalienable if they are real – endowed in the nature of the cosmos – rather than merely rational.

The second case study comes from Martin Luther King Jr. His argument for desegregation wasn’t based on a rational argument. It was based on a deeply moral argument. Human rights are only inalienable if they are real – endowed in the nature of the cosmos – rather than merely rational.