But that’s not the case everywhere. From its lofty seat in the lap of America’s publishing culture, the New York Times recently reported that things are different in Europe, where book sales are actually up. Not that everyone’s celebrating. Despite growth in sales, publishers there are cautious. Even nervous. They’re looking back to events unfolding after 1929. Several French publishers failed during the Great Depression. Perhaps America’s slump portends what’s to come.

“Now we are asking ourselves, will it be like that again?” said one French editor quoted in the story. “There is still a sense of fragility.”

She says what we all know, what we all fear. There is little certainty about the future. No one has visibility. But that’s not necessarily a bad thing. Listen to what economist Israel M. Kirzner says in Competition and Entrepreneurship:

Because the participants in this market are less than omniscient, there are likely to exist, at any given time, a multitude of opportunities that have not yet been taken advantage of.

Uncertainty means opportunity. Anyone can take the available knowledge and arrange his options A, B, and C. That’s what happens now when we conduct business as usual or spend our moments worried about what’s going to happen next. The entrepreneurial function is to put aside A, B, and C and discover D, G, and Q instead.

The Times mentions just such as case:

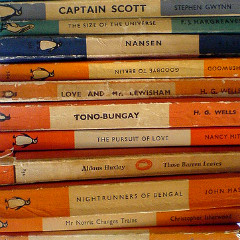

Penguin was founded in 1935, during the Great Depression, by the publisher Allen Lane, who wanted to sell quality books for roughly the price of a pack of cigarettes.

It worked. In less than a year the company had already printed over a million books. Penguin’s success was as then unpredictable as it is now legendary. While his colleagues were failing, Allen Lane figured out one way to serve his customers and grow a business.

Thomas Nelson, the company for which I work, has a similar history of finding D, G, and Q. It’s founder and namesake not only published affordable editions of popular books like John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, but he also serialized the Scriptures so people could buy the Bible in pieces rather the invest in what was then a relatively expensive product. He hired traveling salesmen to field orders for his books, a first in 1829. Then in 1850 Thomas Nelson Jr. created the rotary press, a development that more than doubled the efficiency of printing and revolutionized the business. These innovations changed publishing and brought Nelson growth. And no one saw them coming.

Omniscience sounds great. Certainty would be wonderful. But maybe not. The unequal dispersion of knowledge creates opportunity and space for growth. Allen Lane had an edge. So did Thomas Nelson. Working in uncertainty means using it to our advantage.

I think the message of Penguin and Nelson is that while our environment has an impact on us we are not utterly dependent upon its externalities. We have unique internal energies that can be directed outward to serve customers in creative, as-yet-unforeseen ways and thereby overcome the environment. Put another way, it is because we don’t know what will happen in the future that we have power to steer the present.

What are some of the ways you think publishers can innovate in the current environment?