A publisher and a rabbi walk into a kosher restaurant. . . .

That’s not the setup to a joke. A few years ago I had lunch with Rabbi Daniel Lapin at the wonderful Grins Vegetarian Café in Nashville (then and maybe now the only kosher joint around). We talked about several different things, among them our families.

“You know why God gives us children, don’t you?” he asked me.

“Why?”

“So that we’ll stop being children.”

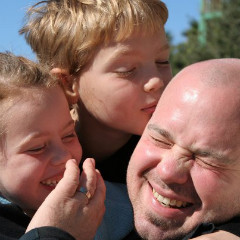

I’ve thought about that ever since and think it’s basically right. I have two children, a boy and a girl, and can attest that raising kids occasions more sacrifice than you ever imagine going into it. In my experience it brings a mysterious sort of satisfaction and joy marbled with weariness and pain. I consider the latter growing pains—the fear of failing, the frustration of doing badly, the regret of missing a chance to do something better. These are the stuff that maturity is made of, doing good for another and being sharply aware that you need to improve and do better.

On the flipside, while it’s far from a scientific observation, I know many childless adults who are remarkably self-indulgent and basically unaware of the fact (at least I hope they are). They are functionally the children that Rabbi Lapin suggested.

An article in the Atlantic recently waded into these choppy waters, suggesting that parents’ happiness should not be a concern in raising kids. For starters, most parents report less happiness in their lives than nonparents. We shouldn’t be surprised. Raising kids is hard work. So perhaps a focus on happiness misses the point. Doing violence to the nuanced way in which the writer presented his case, let me just grab a couple of snips:

It’s fine to go through life happy . . . but I suspect we also want to go through life without becoming big fat self-absorbed jackasses. Children really help in that regard. . . . Instead of asking parents and non-parents whether they are happy right now, we might ask whether they are becoming more like the people they want to be. And then we might see children not as factors that may or may not be contributing to our happiness, but as opportunities to practice what most of us—perhaps me most of all—need to do more often, which is to put someone else before ourselves.

This is not to suggest that having kids is the only way to grow up (the comments on the Atlantic piece would suggest that people get prickly about this), but it is clearly one very good way to do it. The reason is simply enough: teaching us self-sacrifice instead of self-indulgence.

Put the right lens on that and a useful perspective emerges. Call it growing up, call it maturing, call it whatever, but one reason God gives us kids is to sanctify us, to become more like Christ, whose very identity is wrapped up in self-emptying and sacrificial love.