Abraham Lincoln’s early years were marked by a rabid antagonism toward Christianity, but he ended his life as a believer.

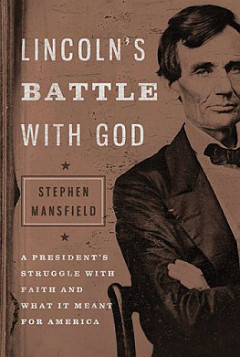

As my friend Stephen Mansfield details in his new book Lincoln’s Battle with God (published by Thomas Nelson), he was an iconoclast, a gadfly, and an intellectual bully. Well versed in the contradictions and problems with Christian scripture and doctrine, he was more than happy to bat believers around the head with these things.

Lincoln even published an incendiary tract arguing against the basic tenets of the faith. His anti-Christian sentiments were so strong that locals referred to him as an “infidel” and friends worried his reputation would cost him socially and politically. But Lincoln kept it up.

Among the many doctrines with which he took issue was the virgin birth. Friends reported that Lincoln referred to Jesus as a “bastard.” His own mother was an illegitimate child, and Mansfield argues that this fact offers insight into Lincoln’s psychology. Being a bastard was something both negative and very close to home.

It’s not that Lincoln did not believe in God. He felt cursed by him.

“Lincoln truly suffered in life,” Mansfield said in a recent interview. His mother died when he was young. His father was abusive. He battled near-suicidal depression. He married an unbearable woman. And then his boys died. The first, Eddie, died before his presidency; the second, Willie, died amid the war that rent his heart along with the nation. The events of life bludgeoned his confidence, driving him to place his faith somewhere other than his own capacities and strength.

“I think his suffering drove him to faith and deepened his faith once he got to it,” said Mansfield.

Through a critical and nuanced look at the evidence, Mansfield chronicles the difficult spiritual journey undertaken by Lincoln, the challenging occupation at which his troubled soul labored until his untimely death. It’s impossible to say the extent of Lincoln’s belief, how far he went, what hopes he ultimately held. But what is impossible to miss is that Lincoln did move from a skeptical anger at God to an appreciation of his maker, even a certain reliance.

It’s intriguing to contemplate one of the last conversations Lincoln had before dying. “We will visit the Holy Land,” he said, speaking to his wife, “and see those places hallowed by the footsteps of the Savior.”

From bastard to savior.

There are probably more questions about Lincoln’s faith than answers, but Lincoln’s Battle with God does a compelling job of mapping the grooves cut in Lincoln’s heart by faith and tragedy and the many impressions they left in his policy and in his public pronouncements.