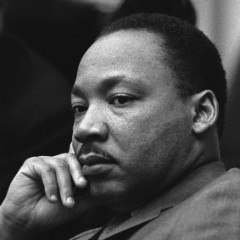

In the fall of 1956, Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. gave a speech and asked his audience to imagine that the Apostle Paul had penned an epistle to American Christians just as he had done nineteen hundred years before to believers in Rome, Galatia, and Colossae.

What would he say? Since the apostle usually wrote to encourage and convict, what faults might he seek to correct?

According to the imaginary letter that King presented, Paul took particular offense at disunity in the church, including racial division. “You have a white church and you have a Negro church,” he said. “How can such a division exist in the true Body of Christ?” Such divisions are “against everything that the Christian religion stands for.”

One need only consult Paul’s real epistles—Romans, Galatians, and Colossians—to see what King is getting at. Consider this from Colossians: “[Y]ou have put off the old self with its practices and put on the new self, which is being renewed in knowledge after the image of its creator. Here there is not Greek and Jew, circumcised and uncircumcised, barbarian, Scythian, slave, free; but Christ is all, and in all.”

Basic Christian doctrine teaches that humans are made in the image and likeness of God. We are all living icons of Christ. While that image was defaced in the Fall and damaged by sin, it is still a fact of our nature, and in Christ this image is “being renewed,” as Paul said.

Communion with both God and our fellow man was sundered in the Fall. Fratricide followed our expulsion from the Garden, and every kind of hatred and division came with it. But as our nature is restored, our communion is reestablished with God as well as man. Ethnic distinctions need no longer divide because “Christ is all, and in all.”

Racism is “against everything that the Christian religion stands for,” as King said, because the Christian faith is about elevating man’s fallen nature and restoring divine and human communion. But racism refuses to see the image of God in another. “The segregator relegates the segregated to the status of a thing,” said King, “rather than elevate him to the status of a person.” The racist does not see Christ in all, only in himself, and it is a false Christ. As a result, the racist misses the grace and goodness that God gives because it manifests in people and communities he spurns.

Martin Luther King Jr. taught one basic fact: that we should esteem all of God’s children regardless of color, that we should honor God’s image wherever and in whomever we find it. As we uphold King’s memory today we should view his task as incomplete as long as we devalue, obscure, or ignore the image in others.

If we cannot see Christ in all, then we will not see Christ at all. King said as much in his close of Paul’s imaginary letter to American Christians: “As John says, ‘God is love.’ He who loves is a participant in the being of God. He who hates does not know God.”

Previously published, January 2011.