The late 1960s and ’70s were a time of fear. Paul Ehrlich told us the world would run out of food and natural resources due to overpopulation. Popular movies like Soylent Green and long lines at the gas pump only seemed to confirm the grim forecasts of his 1968 jeremiad, The Population Bomb.

Environmentalists felt the chills of an oncoming ice age and magazines as well regarded as Science gave credence to the notion that “a full-blown 100,000-year ice age” was “a real possibility.” Said Nigel Calder, former editor of New Scientist, “the threat of an ice age must now stand alongside nuclear war as a likely source of wholesale death and misery for mankind.”

Nukes were no small worry then, either. Growing up in the 1950s, school kids across the country regularly practiced bomb drills the way they today practice fire drills — only more often. Throw in Kruschev’s banging shoe and the Cuban missile crisis, and Americans were prepped to think and fear the imminent worst. Barry Goldwater’s chances at the White House were ultimately nixed by a single Lyndon Johnson TV ad which led viewers to believe that electing the Arizona Republican would install a wildcat with an itchy trigger finger behind the launch computers. Movies like Dr. Strangelove played on the fears. The first Planet of the Apes film assumed we already had blown ourselves to smithereens; part two blasted us again for good measure.

Even something as beneficial to humankind as technological advancement was pooh-poohed by some and became the cause of nail-biting for others, worried the information boom would lead to societal destabilization.

Regardless of the fact that such concerns seem naïve and absurd today, 30 years ago the prospect of being hit by a hydrogen bomb while hungrily waiting in the cold for a gallon of gas left a decade of Americans very afraid and fretting the nastiest.

“The uncertainty prevalent in the world today, now that the international order is so unstable, drives people to look for something to hold on to,” wrote church historian and biblical scholar Cornelis Vanderwaal in 1978. What millions reached for was “prophecy.”

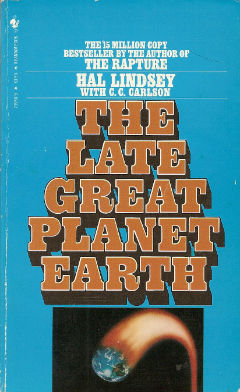

In the midst of the nuttiness and screwball insanity of the come-apart-at-any-minute world, people were itching for answers. It was this chaos that painted the necessary backdrop for the scene that was already beginning to unfold in the 1970 publication of Hal Lindsey’s book, The Late Great Planet Earth.

In an age marked by its increasing secularism and New Age, Easterny, powder-puff religions, the publishing world was hardly ready for a small fundamentalist paperback to assault the bestseller lists like the charge of the Four Horsemen — neither did it anticipate Lindsey’s staying power. Plenty of premillennial dispensationalist books had been published before Late Great, but most to meager success — especially when stacked against Lindsey.

In the book’s first seven years it sold 10 million copies. The New York Times named the former tugboat captain the bestselling author of the decade. Before the close of the millennium, Lindsey’s book had sold over 35 million copies and had been translated into more than 50 languages.

The reason for the runaway success?

“If I had been writing 15 years earlier, I wouldn’t have had an audience,” Lindsey told Publisher’s Weekly in 1977. “But a tremendous number of people were beginning to worry about the future, and they were looking everywhere for answers. The turn to the occult, astrology, Eastern religions, and other movements reflected the fear of what was going to happen in the future. And I’m just part of that phenomenon” (emphasis added).

Lindsey’s message was born from a womb of fear and continues to thrive on a diet of international unrest — especially anything unpleasant in the Mideast. The swell has likewise picked up scads of hangers-on. Since the publication of Late Great, doom peddlers have been surfing on a wave-crest of crisis and terror. Despite his fright-flinging forebears and the current clutch of catastrophe-mongers, however, Lindsey is the alpha of the end-times omega.