Magic is part of our legacy as humans.

Witchcraft is a tool for those denied power through ordinary means.

Magic and witchcraft are available to everyone. You don’t need an invitation and you certainly don’t need anyone’s permission.

The power is there for the taking. But you have to take it, nurture it, tend it, and most importantly, exercise it.

Over on the new Pagan blog The Southern Light Diaries, Marshall (the Witch of Southern Light) has an excellent post titled A Case for the Exclusive Cunning Arts. I encourage you to read the whole post, but here’s a key quote:

Anyone can do witchcraft, but not everyone will have what it takes to be a witch … A witch is cunning. A witch is resourceful. A witch knows themself. A witch studies. A witch goes to the edge of discomfort and then keeps going.

A witch puts in the work.

Marshall does a great job of demonstrating how those who want to be spoon-fed will never become competent witches and magicians. I’m not going to replow that ground. Instead, I want to talk about what can happen when you decide that yes, you really do want something badly enough to put in the work.

Neither Protestant work ethic nor anarcho-primitivism

Any time I mention the necessity of work someone accuses me of being a crypto-Protestant or some similar piece of nonsense. Trust me – I left the Protestant work ethic behind with all the other bad ideas of Calvinism when I managed to extract the tentacles of fundamentalism from my soul. Material wealth is no sign of divine favor and hard work is not an intrinsic virtue.

It is, however, a necessity.

There’s a current of anarcho-primitivism running through much of contemporary Paganism and witchcraft. This is the idea that we’d be better off if we returned to some sort of pre-industrial and pre-agricultural society, where we feed ourselves through hunting and gathering and spend most of our time sitting around telling stories.

I’ll admit there are days when that looks attractive, at least when I don’t think about how to shrink the population to a point that could be sustained by hunting and gathering. But on the whole, I prefer travel and modern medicine (especially anesthesia) and the ability to write something and have it seen around the world in a matter of seconds.

If the Protestant work ethic overvalues work, anarcho-primitivism undervalues it. I’m not interested in just existing. I want to learn and grow, I want to experience as much of the world as I can, and I want to shield me and mine and as many others as possible from the randomness of life.

Building any skill requires work. It requires study and practice. This is true of playing a musical instrument or painting or running a marathon.

Or working magic.

Do you want to call yourself a witch or do you want to do witchcraft?

It’s time for my usual disclaimer when talking about these things: I do not call myself a witch (for now, anyway). I’m a Druid, there’s plenty of magic in Druidry, and I don’t need another title.

But I absolutely do witchcraft.

I have a theory of magic and I teach a class in magic. I work magic at the full moon. And while I consider baneful magic to be a last resort, I’m perfectly willing to throw a curse when necessary.

I couldn’t do these things (not effectively, anyway) if I just called myself a witch or a Druid. Yes, there’s power in a name, but that’s the power of beginning, not the power of mastery. I can do these things because I’ve studied them and practiced them and done them over and over again.

A few years ago I realized my magical skills were slipping, because I wasn’t exercising them enough. So I started working magic once a month, every month. If had nothing that was urgent, I looked a little deeper – there’s always something in my life that can use a magical boost. The extra practice has been very beneficial.

Do you just want the title? Or do you want the skills that come from doing the work?

Is it really work if you’re enjoying it?

“Work” is a loaded word in contemporary English. Between the Calvinists and the anarcho-primitivists, it carries emotional baggage that far exceeds its plain meaning. Most times “work” is something we do because we have to do it, because of the way society is structured. But we also use it to simply mean “activities done toward a desired end.”

The phrase “do something you love and you’ll never work a day in your life” is a lie. Do anything for very long and there comes a time when you’d rather be doing something else. Maybe anything else. One of the reasons I’ve resisted the urge to make my spiritual work my job is that I’m afraid that at some point, it would become just a job – a job I no longer do because I love the work, but because I need the money.

I find spiritual work fulfilling and enjoyable, but even without the pay it can be every bit as tiring as ordinary work.

Still, I keep doing it precisely because I find it fulfilling and enjoyable. And because I’ve made commitments to certain deities and other persons, but that’s another topic for another time.

Do you want to be a witch badly enough to keep doing witchcraft even when it’s hard? Even when you get tired? Even when you’re tired of it? If you don’t, you may develop some skills, but you’ll never grow into the witch you could be with consistent effort.

“Do your own work” is not gatekeeping

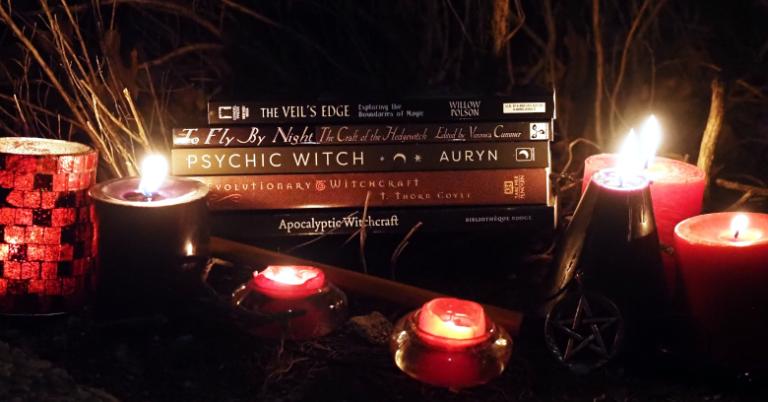

There was a time when information on witchcraft was hard to find. That time is well in the past, as the “Barnes & Noble Witches” of the 1990s will testify. It’s even easier today in this era of Amazon and the internet. We’re living in a golden age of magic and witchcraft. Information is readily available, practicing is safe (in the sense that there are no witch hunters in the West – magic itself is never safe), and the currents of magic are stronger than they’ve been in centuries.

Of course, not everything is published in a handy pocket guide from Llewellyn (and that’s not a knock on Llewellyn – they’re a great company and they publish my books). There are some things that cannot be explained – they have to be experienced to be understood. The phrase “life’s not a destination, it’s a journey” is sometimes misused, but it’s true. What we learn on the path is at least as important as what we achieve when we get to where we’re going.

In the case of witchcraft, that includes figuring out how to find information and materials. Sometimes you have to work one spell to find out how to work another spell. Or the information you need isn’t in this world and so you have to go into the Otherworld to get it. Or the spell you have is impossible to translate (many ingredients in the grimoires and in the PGM are codes words for ordinary items, but sometimes they’re not) and you’ve got to take your best guess, see what happens, and then make adjustments for your next try.

Sometimes you fail. But even then you learn something. And when you succeed, not only do you get what you were working for, you build the skills that will make the same process easier and more reliable in the future.

What do you want out of magic?

At the end of the day, what really matters is this: what do you want out of magic? What do you want out of witchcraft?

Do you want the power to shape your reality?

Do you want the ability to shift the odds in your favor?

Do you want the skills to form and maintain relationships with the various spirits around you?

Do you want the confidence that comes from knowing that no matter how dire the situation, you are never powerless?

Almost everyone can do these things. Only a few will. Fewer still will do what is necessary to become truly skilled with them.

There is no shame in choosing another path. Everyone can do it, but it isn’t for everyone. If this isn’t for you, I wish you well in your chosen endeavors, whatever they may be.

The power is there for the taking. But you have to take it. And nurture it, and tend it, and exercise it.

How badly do you want it?