To mark and celebrate the release of the Common Prayer Pocket Edition this month, we’re running a series of interviews with scholars and wise elders who’ve helped to shape the common prayer movement that is at the heart of The Everyday Awakening in our time. If you missed it, you can check out my interview with Steve Harper here.

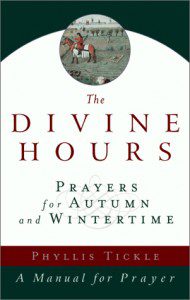

No one has been more important to the contemporary renewal of liturgical prayer than Phyllis Tickle, the founding Religion Editor at Publishers Weekly and widely respected commentator on religion in America. Her Divine Hours, designed to invite individuals into the ancient practice of fixed-hour prayer, have set the standard for contemporary prayer manuals.

At the very beginning of our Common Prayer project, Shane Claiborne and I conferred with Phyllis, who graciously and helpfully served as an advisor to our project.

After taking us through the ins and outs of various details related to the publication of liturgical materials in our initial conversation, she paused and said with great seriousness, “But listen: you can’t mess around here, boys. You’re dealing with the very song that’s sung around the throne of God.” I recalled her admonition every morning I worked on Common Prayer. It was a delight to get to converse with Phyllis again about the renewal of liturgical prayer and what it might mean for us in our time.

JWH: With your Divine Hours, you’ve been inviting people into the practice of fixed hour prayer for over a decade. What is your sense of who’s drawn to liturgical prayer? Why are people using prayer manuals and how are these tools shaping their relationship with God?

PT: In the mid-1990’s, when Doubleday first approached me about the possibility of compiling a set of contemporary prayer manuals for the keeping of the liturgical hours, they spoke in terms of “the liturgically mobile” as being the perceived audience.

“Whatever,” I asked, “does that mean?”

Well, it seems it meant—and quite accurately so—that vast numbers of American Christians were [and are] on the move toward less idiosyncratic and more foundational practices of faith.

The head of Doubleday Religion at that time, a devout Roman Catholic named Eric Major, further quipped, in answering me, by saying, “These days it’s born a Baptist, die a Methodist; born a Methodist, die a Presbyterian; born a Presbyterian, die an Episcopalian; born an Episcopalian, die an Orthodox…liturgically mobile…liturgically on the move…liturgically going home.” And he was right. We are using the liturgy of the Church and of our forebears to go home again.

JWH: Yes, we’re on the move. The practice of faith is in flux for so many people. But in the midst of that, how do you explain the current attraction to fixed hour prayer?

Christendom is dead, and may it evermore remain that way. But with the demise of Christendom has come the necessary distinction between being a cultural Christian and being an observant one. That is, the Christian who would be more than just a citizen of a christianized culture must now find his or her practices and postures, understandings and professions, in something deeper and grander than the surrounding status quo. He or she must, out of necessity as well as hunger, turn to those observances and modes of worship that grew the early Church and that still form the grounding roots of her today. And of those ancient disciplines and ways of being, none is more accessible, more easily learned or more demanding, more efficacious or more intimately formative than is the discipline of fixed-hour prayer.

The late Robert Webber was as astute an observer of American Christianity as ever there was. In the early 1970’s he wrote a seminal book entitled EVANGELICALS ON THE CANTERBURY TRAIL in which he argued that late 20th century western Christians, especially evangelical protestant ones, were passionately in love with what he called “the ancient future” and were already finding their way toward it by re-visiting the liturgies, customs, symbols, and implements of the early Church. We were doing this, Webber observed, with an eye toward borrowing and adapting those ancient treasures to contemporary use and in such a fashion as to satisfy contemporary needs. He was right, of course; for that is exactly what has happened and is still happening and, from all appearances, will continue to happen for many a year to come.

What Webber also undoubtedly saw but didn’t say was that the prayer book and the daily offices would prove to be the easiest of the ancient ways for post-moderns to move into. There is—and always has been—a certain romanticized cachet about prayer books and chanting monks. One did not– and does not– have to be Christian to understand the art of the prayer book as an object or the mysterious appeal of the chanting monk as a symbol of interlocutor with the Divine. We see the books in art history texts and influential museums. We hear the monks in bad movies and also in some very fine ones. Their very ubiquity makes them, for the neophyte and/or the hesitant, less threatening and more palatable as ways into deeper Christian practice.

With prayer manuals and the observance of the offices, that is, there are fewer barriers along the road of moving from being a secular Christian to being an observant one….or, and this is perhaps more often the case in this country… from being an already persuaded Christian to being a more incarnational and disciplined one. There are, of course and ironically, no more powerful, gripping, and efficacious ways to do that either; and in a sense, that is the great joke of the thing: what seems at first blush to be the most harmless becomes, with practice, the most persuasive and formative of all the traditional practices and…let us confess it…the most defining.

JWH: As a student of American religious history, how do you see prayer movements connected to social movements in our society? Is liturgical prayer shaping more than people’s devotional schedules?

What we have never seen before in American religious history is the ubiquity of lay monasticism among folk of all classes and personality types. The whole thing is so remarkable, in fact, that we’ve had to invent the term “neo-monasticism” to name it. Deeply communal, egalitarian before God and humanity, disciplined by tradition, and marked and instructed above all else by the rhythms of the daily offices, neo-monasticism is one to the two fastest-growing expressions or presentations of Emergence Christianity today.

The inevitable result of neo-monasticism’s defining practice of returning to the keeping of the daily prayers is the increasing presence of the kingdom of God in daily life. Jurgen Moltman, perhaps the most influential of our living theologians in Western Christianity, has observed…many times, in fact…that the future of Christianity is the Church, and the future of the Church is the Kingdom of God. He’s absolutely right; and the move toward the resumption of the ancient disciplines, and especially toward that of fixed-hour prayer, is a movement beyond Church and toward both the Kingdom and Kingdom living. That shift will effect every part of everything for Christians and, by extension, for the world around us and for whose translation we live and pray.

JWH: You’ve written and spoken a great deal in recent years about “emergence Christianity.” What role is prayer playing in the transformation that you describe? What are your hopes for the next ten years?

Our return to the observance of the daily offices is also, of course and more or less by default, a return to the observance of the liturgical year. The appointed readings and prayers for every office every single day reflect and rotate with the cycling emphases and holy seasons of the Church’s year itself. What that means, in effect, is that a return to the practice of fixed-hour prayer is a return to daily, lived, intimate contact with the Christian story…with the narrative more than with the propositions that have derived from it…with the poetry of faith not just merely with its doctrine and factuality…with the bonding of the heart and mind of one believer to the heart and mind of the whole.

What I think…perhaps, what I hope and certainly what I pray for….is that before Emergence Christianity is done with us, it will take that translating effect of the daily offices and their narrative flow back into the everyday flow and shape of our homes. What I hope, in other words…what, indeed, I think is already happening…is that the resurgence of fixed-hour prayer in lay practice is, and will go on, returning us to that other, most ancient and most central of practices, namely to the domestic transmission of our faith on a daily, natural, and yet very intentional basis.