The following is a summary, from my pastor (Paul Strawn), of the article in German “’Das Word sie sollen lassen stahn…’ Die Auseinandersetzung Johann Gerhards und der lutherischen Orthodoxie mit Hermann Rahtmann und deren abendmahlstheologische und christologische Implikate.”, from Zeitschrift für Theologie und Kirche 95 (1998), 338-365.

This is translated as: “’The Word they still shall let remain…’ The Debate of John Gerhard and Lutheran Orthodoxy with Hermann Rahtmann and Its Implications for the Theology of the Lord’s Supper and Christology.”

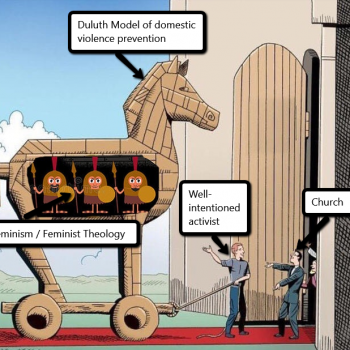

From Strawn (please note, the title of this post, as well as the choice of pictures accompanying this post – along with their captions – are fully my doing):

In this article, appearing almost twenty years ago, Johann Anselm Steiger, professor of church history and the history of dogma at Hamburg University, compellingly promotes a reconsideration of the doctrine of the Word of God as formulated by the theologians of the early period of Lutheran orthodoxy.

Locating its definitive formulation in Johann Gehard’s “Von der Natur, Krafft vndt Wirckung des geoffenbarten vndt geschriebenen Wortes Gottes” [“Concerning the Nature, Power and Effect of the Revealed and Written Word of God”] from 1628, Steiger notes how the theology found there was forged in a long and far-reaching debate centered around the city of Danzig commonly known as the Rahtmann Controvery.

Hermann Rahtmann was a Lutheran pastor who, in seeking to defend the orthodoxy and usefulness of the writings of Johann Arndt, came to promote the idea that the Bible had no power in and of itself to convert, but it was only useful and helpful to those who had already been directly enlightened by the Holy Spirit. Thus the question was raised again, which had been raised years before by Casper Schwenckfeld, and that is: What is the relationship of the Holy Spirit to the Bible? To preaching? Could the Bible, could the conveyance of the Word of God in written and oral form be said to have any power in and of itself?

[note: Strawn also has addressed Schwenckfeld – and his very interesting conflict with the Lutheran polemicist Matthias Flacius – see here]

Rahtmann’s rejection of the idea was a result of observing that not all who read or heard the Word of God repented of their sins, believed the gospel, or were comforted by it. Since that is so, Rahtmann reasoned, it just must be that the Word of God as it found in creation is nothing out the ordinary. It merely contains signs pointing to the greater things signified.

Gerhard responded to this assertion by noting the similarities of the relationship of the written and spoken Word of God to the Spirit of God and that of (1) the divine and human natures of Christ, (2) the presence of the body and blood of Christ in the sacrament of the altar, and even (3) the relationship of the human soul to the body. As Christ died on the cross for all mankind, but many reject what was won for them there, as Christ is present in the Lord’s Supper, but not all benefit from that presence, as the soul of man exists within his body, but cannot be seen, so the Holy Spirit is present in and united with the Word of God as it is found in the Bible, and as it is proclaimed. Thus whether in use or not, the written Word of God must be said to have power, power which nonetheless is effective only when it is properly deployed.

As it is, however, it is a word that does what it says, and says what it does. The preaching of the Word was just as much an audible sacrament as the sacraments were the visible Word. Even then, the Sacraments were “Word events” occurring through the preaching of either the Trinitarian invocation or the Words of institution.

Yes, distinctions had to be made between (1) the Word which Christ brought with Him “from the womb of the Father,” (2) the Word engraved in the hearts of the apostles and prophets by the Holy Spirit, (3) the Word transcribed by biblical Scribes and included in the Scriptures, and (4) the Word that is read today in the Bible, heard in sermons, and believed. In other words the Word of God is both Trinitarian—flowing from the Father, Son and Holy Spirit—as well as incarnate: Appearing in time and space. Here the Lutheran Gerhard, so Steiger, predates Karl Barth’s similar (revolutionary!) Trinitarian presentation of the outgoing of the Word of God—a fact never acknowledged by Barth.

But did identifying a fourfold outflowing of the Word of God from its Trinitarian source mean that the individual manifestations of that Word should be separated from each other and examined? Gerhard’s answer was no. If such were to occur, such a theology would be created that would never allow man to be certain of his salvation.[1] And ultimately, such a pastoral concern, and another similar to it, drove Gerhard and the other Lutherans at the time to come to a greater understanding of the Bible’s relationship to the Holy Spirit. For if not just the Word of God, but the Bible, as Word of God, did not possess power in and of itself apart from its use, what good would it be for Christians to turn to it and read it in time of need? (bold mine)

FIN

Further reading: Re: more on the early Lutherans and the interpretation of Scripture see here ; for the influence of Kant in particular on modern theology, including Barth, see here.

Notes:

[1] “Wollte man sie voneinander trennen, würde dies >>eine wunderseltzame Theologiam geben/ bey welcher man nimmermehr zur Gewiẞheit kommen köndte.<<“ P. 362, n. 96.