Editor’s Note: The following is an excerpt from AFTER THE FLAG HAS BEEN FOLDED (Wm. Morrow). When I hear people pontificating about abortion (pro or con), I remember this girl…

My brother called me on a Sunday afternoon. It was the first time we’d spoken in months. His voice was gentle but firm. “Karen, don’t do this,” he urged. “I’ve been studying up on this in my Bible study group. Abortion is murder. Have the baby, give it up for adoption. Let Mama raise it, but don’t do this, please.”

I was touched by his concern but angered by his interference. “Isn’t it funny that you are now giving me advice when for so many years you did nothing but cause grief for all of us around here?” I asked. My words were intended to burn him. It worked.

“I know, I know,” he said. “But don’t mess up your life just because I screwed up everything in mine.”

Frank tried to explain to me why abortions were wrong and why I ought to reconsider. He quoted numerous Scripture verses on the value of life. I heard him, but I didn’t listen. He had long since lost the right to be my advisor. It had been years since I’d admired him or valued his opinions. It would be another decade before I would do so again.

I knew Mama could stop me from having an abortion by refusing to sign for it. But I also knew she wouldn’t do that. She always subscribed to the theory that once a person makes up her mind, there is little anyone can do to dissuade her. Mama hadn’t really had a handle on parenting any of us for quite some time. Our relationship, in particular, had always been a tumultuous one. Our personalities frequently clashed. I was emotive and backtalked her all the time. Mama didn’t much care for emotions. They complicated life. And she rarely, if ever, expressed her emotions in words.

She once pitched a can of beans at my head in a fit of anger. It was her way of telling me to shut up. I ducked and the can crashed clean through the wall behind me. That scared us both so bad neither of us said a word for a minute or two. Then we both burst out laughing. I think that was the closest I’ve come to being decapitated, thus far. As far as I know, those beans are still in the walls of that house on Fifty-Second Avenue. Mama just plastered over the hole without ever retrieving the can.

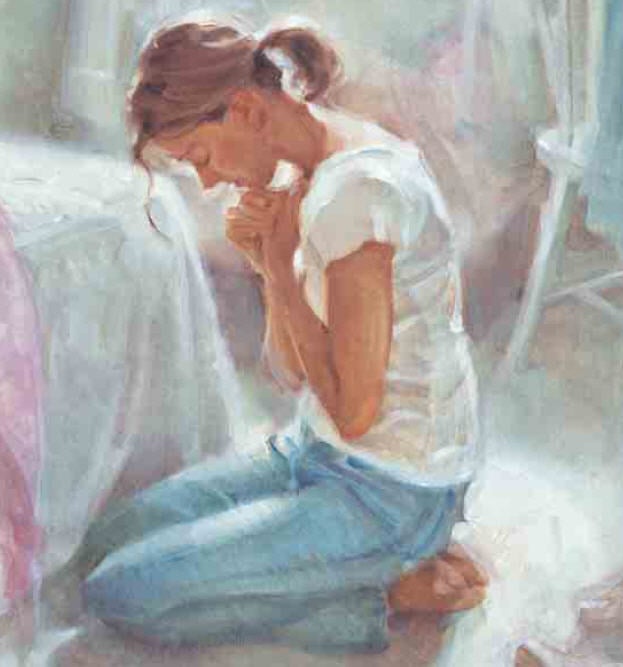

I didn’t really value Frank’s or Mama’s opinion one way or another about the pregnancy. Still, I did have enough sense to realize that I had to patch things up with God as quickly as possible. I was obviously a failure at handling things by myself. I grabbed my Bible after school one afternoon and drove over to Rose Hill Baptist for a meeting with Pastor Smitty.

His office was located on the second floor of the building, down the hall and around the corner from the primary and nursery classrooms. His door was open but I knocked on it anyway. Smitty had a pen in hand and was studying a book.

“Karen, come in, come in,” he said. He rose from his chair and gave me a big grin. Smitty was a handsome man when he smiled, which he did almost all the time. A bomber pilot during World War II, he possessed that natural athletic look. His brown hair was graying, but it still as thick as it was when he was twenty. He had broad shoulders and a trim waist. Had he lived, I imagine my own father might look like Smitty, only Daddy would surely have had less hair. It was already beginning to recede when he was killed. “Have a seat,” Smitty said, waving to the leather armchair facing his desk. Books filled the shelves behind him.

“Thank you, Pastor,” I said. My hands were sweating and my face was flushed. I gripped the Bible in my left hand and offered him my right one. Smitty shook it. I had never been in his office before, for any reason. It was more daunting to me than the principal’s office. Smitty, after all, was a man of God.

Other than Charlie Wells, I’d never really talked to grown men about things of a personal nature. And that didn’t count, because Charlie was more of a pal than an authority figure. But Smitty was definitely in a powerful position, appointed by Almighty God himself. My heart was beating so hard I could hear it in my ears. “I’m glad you called,” he began.

“Well, I don’t know but I imagine you might have heard some rumors, sir,” I said.

“As pastor, I’m always hearing things, Karen,” he said reassuringly. “But I don’t pay much attention to rumors. Why don’t you tell me what’s on your heart?”

That invitation was all I needed. For the next half hour, I told Smitty everything. About my feelings of frustration, anger, and abandonment. I told him about my awful prayer, telling God where to get off. And then, about how I’d barreled headstrong into this relationship with Wesley Skibbey, fully intent on getting pregnant so I could finally have the affection and love I sought. And about how, too late, I came to realize what poor choices I had made and, ohmygosh, what was I going to do now? I didn’t think Mama capable of raising a baby. Besides, I knew what it was like to grow up without a father, and I didn’t want any child of mine to grow up like that.

I told him about Frank’s phone call and his admonishment to not have an abortion because it was murder in God’s eyes. And about how angry it made me that my brother dared to make such a phone call after all his foolishness over the years.

I told Smitty all this in an urgent and intense manner, the way a bystander tells a cop about the horrific wreck he’s just witnessed. My confession was punctuated by sobs of shame. Smitty reached over his desk and handed me a box of tissues. He leaned back in his chair. His hands were crossed in thoughtful reflection. I knew he was searching and praying for the right words to bring me both comfort and wisdom. I was praying for the same thing. He let me cry in silence for a while before speaking.

“Karen, it’s a terrible situation for you to be in,” he said. His tone was soft. Smitty never spoke with a tone of condemnation. Even when he preached, he wasn’t preachy. He was a teacher at heart, imparting life’s lessons as best he knew them. “What does your mama think?”

“She was the first one to suggest I have an abortion, sir,” I replied. “But then, I think it was after she talked with Frank, she changed her mind. She’s decided she wants to keep the baby and raise it herself. But I could never let her do that.”

“You could always adopt the baby out,” Smitty said.

“Yes, sir, I thought of that. But I’ve decided I really want to go to college. And I have five more months to go until graduation. I’d have to go away somewhere.”

Nobody went to school pregnant at Columbus High in 1974. At least not visibly so. There were no school programs for pregnant teens. Girls who got pregnant always disappeared for six months or better.

Smitty considered the situation before advising me further.

Uncomfortable with the silence hanging between us, I blurted out, “I just don’t know what’s the right thing to do.”

“Well, Karen,” Smitty said thoughtfully, “in situations like these, I’m not sure there is a right thing to do. You’ve made a terrible mistake. When we invite sin into our lives, we are left with the consequences of our choices. The question before you is what’s the best thing you can do now that the wrong choice has been made. You have a list of consequences to choose from. I can’t tell you which one to pick. That’s a decision that you will have to make. But I know whatever you decide, your church family is here for you. We care a great deal for you. We want to help in any way we can.”

I didn’t question for one moment Pastor Smitty’s concern for me. I knew he cared immensely about all people.

___

Mama wrote a note for a pre-excused absence that I had to take around to all my teachers at Columbus High. She could’ve written a note that said I was going out of town for a few days because somebody in the family had died unexpectedly. She could’ve told them I was going to be visiting college campuses. But Mama’s note said I was going into the hospital to have a D&C. A couple of my teachers looked at me quizzically after reading it.

“Everything okay?” Mr. Dietrich, my music teacher, asked. He often held Bible and prayer-group sessions in his classroom before school. He’d been my teacher for all four years at Columbus High. I missed several of his classes during December because he was my first class of the day and about that time I was usually holding sessions with the porcelain throne.

“Yes, sir,” I said. “Everything’s fine. I’m just having some female trouble, that’s all.”

He signed his name to the note and told me not to worry about missing class.

Marjorie Sewell was the next teacher to express concern. She read the note and studied it for a moment or two before looking at me. “You’re going into the hospital?” she asked.

“Yes, ma’am,” I replied. I was praying that she wouldn’t ask me why. I didn’t think I could lie to her.

She pressed her hand over the note, ironing it out. Three or four other kids crowded around us. She signed her name.

“Karen,” she said.

“Yes, ma’am?”

“I hope everything turns out. If you need anything . . .” Her voice trailed off but her eyes were locked on mine.

“I’m fine, ma’am. Really, I’m fine.” I could feel blood rush to my neck and cheeks as I grabbed the note, folded it up, and stuffed it into a book. Kids poured into the room as the late bell rang. I sat down and avoided all further eye contact with my teacher. I was afraid she knew the truth, and that shamed me.

I was admitted to the maternity ward of Columbus Medical Center on January 29, 1974. My roommate was a black woman who was older than Mama. She already had a litter of kids and didn’t want no more, she told me. Mama had stayed only long enough to sign the paperwork and make sure I was situated. She said she’d stop by during her shift that night and check on me.

I unpacked the overnight bag she’d given me for Christmas. Then I sat down on the edge of the bed and continued reading Richard Llewellyn’s classic, How Green Was My Valley. I needed to finish reading it so I could write a book report. It seemed fitting to be reading a book about how gossip destroyed a minister’s career.

Pastor Smitty had asked me how I was going to deal with all the gossip that would surely circulate among the youth group at Rose Hill.

“I’m not going to worry about it,” I said. “The friends who really love me will come and talk to me about it. The others? Well, they’re going to talk about somebody, might as well be me.”

I wasn’t quite so cheeky when the orderly showed up in the doorway and took me by wheelchair to get a lung X-ray. The technician was Debbie Baker, a good friend of Patsy’s.

Debbie handed me a hospital gown and told me she needed to take a chest X-ray. I never asked why and she didn’t say. We acted as if we barely knew each other as she hid behind a glass pane flipping a switch and I was exposed in a gown as thin as cheap toilet paper, knowing that somewhere on my medical file was the word ABORTION. I felt like somebody had stamped a big red A across my chest. Debbie flashed me her best smile and thanked me. The orderly waited for me to get dressed before wheeling me back to my room.

Sometime that afternoon the doctor stopped by. Somebody had told Mama that Dr. Dennis Whitfield was the only doctor in Columbus who performed abortions. Roe vs. Wade had legalized abortion only a year before. There weren’t big protest groups marching around holding up placards of bloody fetuses. But there weren’t that many physicians practicing suction abortions either, especially not in the South, where life is considered a holy sacrament.

But I’d heard that Dr. Whitfield was not a native son. He was from Montana or Wyoming or some other place out West where hippies lived in communes and had group sex. Dr. Whitfield sure didn’t look like any other doctor I’d ever known. He had reddish blond hair that hung around the nape of his neck. He walked in that same moseying fashion that stoners used, rather than the clip style of the military doctors at Martin Army. He spoke to me as if I was an adult, much the same way Pastor Smitty did.

I followed him to an exam room at the end of the hallway and I propped up on the end of the exam table while he pulled up a chair and grabbed a clipboard. “Karen, I want to explain some things,” he said. “Today, I’m going to insert a substance made from seaweed that will help dilate your cervix,” Then, taking the clipboard, he drew a picture of a tiny hole and then a bigger one. “It shouldn’t hurt or cause you any discomfort. We’ll leave that in overnight. You can’t have anything to eat tonight. That’s because we’re going to give you anesthesia in the morning, and we don’t want you to have an upset stomach. I will use a tool like this.” Dr. Whitfield showed me a shiny long instrument that looked like an enlarged version of the thing the dentist used to clean my teeth. “With it I will scrape out the inside of your uterus. Then we’ll use a machine that’s sort of like the hose on a vacuum cleaner to remove any other fetal tissue. It won’t take long. And you won’t remember a thing. Any questions?”

I shook my head no. I didn’t have the heart to tell him I understood very little of what he said. The mechanisms of my womanhood were as foreign to me as Latin verbs. I’d heard them all before, but I just didn’t know what they meant. The part that really troubled me was that seaweed substance in my privates. That was just plain nasty.

Wes and his buddy Tom were sitting on my bed when I got back to the room. I could tell they’d been smoking pot. They smelled like field hands who’d come in from the noonday sun and they were giggling like a couple of pre-schoolers who’d just discovered Barbie’s pointy breasts. I was annoyed as hell. “Get off that bed,” I said.

“Hey, whoa!” Wes said. “We stop by to pay our respects, and you’re bitching at us.” He and Tom jumped up off the bed.

“I don’t really want you here,” I replied.

“Okay, okay, that’s cool,” he said, smiling. “I’m just trying to do my fatherly duty.” He and Tom laughed. I didn’t.

The old woman in the bed next to mine snorted, apparently put out by their behavior too.

“Listen, go away and don’t come up here no more,” I said. “Especially don’t come up here when you’re loaded.”

Wes and Tom laughed. Bad boys nailed again. They seem to relish the thought.

“Hey, we’re going,” Wes said. “But remember I tried.”

“Yeah, sure,” I said. “Where would I be without you?”

“Probably someplace else,” he said.

“That’s for darn sure,” I quipped.

I was so mad at Wes I could spit nails. About a week before I went into the hospital, I’d found out that he had told his mother I was going in the hospital for a root canal. She’d asked me about it one day when I called up to his place. “Wesley tells me you’ve got to go to the hospital for a couple of days,” Mrs. Skibbey said.

“He told you that?” I asked. I was surprised he’d mentioned anything at all about it to his mama.

“Yes. He said you’re going in for a root canal. But that’s not why, is it, Karen?”

“No, ma’am.”

“I didn’t think so. People don’t usually go in the hospital for dental care. What’s the matter, honey?”

I didn’t know how to answer her. I was furious at Wes for lying to his mama, but I didn’t want to be the one to tell her I was pregnant and her son was the sperm donor. So I didn’t say anything. “Karen, are you pregnant?” she asked.

“Yes, ma’am.”

“I thought so. Are you having an abortion?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“It’s the right thing to do,” she said. “I had one too, you know.”

I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. Pauline Skibbey had an abortion?

“When I was a young girl, living in Germany. They weren’t legal then. But I found a doctor who did it. This is better. You’ll be okay.”

Why did everybody keep telling me that? I wasn’t at all sure my life would ever be okay again.

“Mrs. Skibbey, please don’t tell Wesley I told you,” I replied.

“Don’t worry. I’m not going to say anything about our visit. You deserve better than my son, Karen. Forget about him. He needs to grow up.”

“Yes, ma’am,” I said.

When I hung up I realized that in all the years we’d known each other that was the longest conversation Mrs. Skibbey and I had ever had.

Several more visitors dropped in on me, including the new youth pastor at Rose Hill. His visit just made me feel more ashamed. I knew he and his wife were trying to get pregnant and having trouble. He didn’t know what to say and neither did I. Thankfully, he stayed only a few minutes.

Beth McCombs came and brought me some magazines and a Snickers bar. I’d told her about the abortion shortly after I’d discussed it with Lynn. I was shocked when Karen Mendenhall and her mother, Donna, paid me a visit. Karen thought I was in the hospital to have my tonsils removed. She and her mother hadn’t a clue why I was really there.

I hadn’t told Karen anything about the abortion because her friendship was too valuable to me. I figured if her mama knew the mess I’d gotten myself into, she’d forbid Karen from ever hanging out with me again. Donna Mendenhall was a stern mother. She had a conniption fit when she learned that several of us kids in the youth group had been caught toilet-papering Pastor Smitty’s yard. Smitty and Betty didn’t seem to care; in fact, they had invited us all in for a cola, after we’d cleaned out the trees, of course. But Donna gave Karen and me such a lecture you would’ve thought we’d stolen a car or held up a 7-Eleven store.

Karen told me she found out about the abortion later, from Beth. She also told me that her mother was angry to arrive at the hospital and discover that I’d been stuck on the maternity ward. Donna, who’d quickly figured out why I was really in the hospital, worried about the emotional impact that would have on me.

She didn’t come bearing flowers or candies, but Donna brought me a treasure that night that has lasted me a lifetime – the gift of grace. Her concern for me was only slightly veiled behind her dark eyes. She didn’t mention the word ABORTION. And she didn’t scold me for my folly the way she had the night I’d helped trash Pastor Smitty’s yard. Instead, she reached out her tiny hand and patted mine. “We love you, Karen,” she said.

And I knew that she did. I was never afraid of Donna Mendenhall after that visit. I knew that while her expectations for her daughter – for all us kids – were high, ultimately, she wanted only what was best for us. Her wanting that for me made me want it for myself.

Linda didn’t come by the hospital. I hadn’t expected her to, really. We never talked about the abortion. Not then and not now. I was a big disappointment to my sister. Linda was the lone child that Mama and Daddy really could be proud of. Although the youngest when Daddy died, Linda has handled the loss better than the rest of us. I suspect that’s because she learned from her siblings’ mistakes. But maybe it’s because she was born with a stronger heart. One that didn’t tear so easily. I’ve always envied her that.

Mama did check on me during the night, but we didn’t have much to say to each other. I knew she was wishing I would change my mind. I felt guilty for putting her in a situation where she had to give me her permission to do something she didn’t want me to do. But I was still convinced that letting her raise my child was a bad idea. Pastor Smitty was right. There were no easy answers, just a list of wrong choices from which to pick. I’d made my choice, and Mama was forced to agree to it. Seemed like the only thing we had in common anymore was our mutual resentment of each other.

I woke up early Wednesday morning. Surgery was scheduled sometime before noon. I was not allowed to eat or drink anything. I was terribly thirsty. Mama stopped by after her shift ended. I was lying in bed, reading. There was a lot of activity in the hallway as nurses carted hungry, squalling newborns to their mothers. Any other time I’d have been tempted to sneak off and get glimpses of the babies, but not on this day. “How’d you sleep?” Mama asked.

“Fine,” I replied.

Mama looked tired. I could barely see her brown eyes behind their heavy lids.

“I’m really thirsty,” I said.

“I’m sure you are,” Mama said. “But don’t drink anything, otherwise that anesthesia will make you sick. Has the doctor been in yet?”

“No ma’am, not this morning,” I said.”I saw him yesterday.”

“You sure you want to do this?” Mama asked. “You don’t have to, you know.”

“Yes, ma’am,” I said without pause. “I’m sure.” I didn’t feel nearly as convinced as I tried to sound but I wasn’t about to let on to Mama that I was having doubts. Whenever I felt like maybe, just maybe I ought to keep the baby, I envisioned the bickering that would surely take place if Mama was raising my baby. And if that wasn’t enough to persuade me, I thought about what an absolute cad Wesley Skibbey had turned out to be. The last thing I wanted to do was to be tied to him for the rest of my life.

My answer disturbed Mama. She looked away and began shuffling through the side pockets of her uniform for her cigarettes. When she found the cigarettes and the lighter, she took her leave. “I’m going to go on home and try and get some sleep, Karen,” she said. “I’ll be back later this afternoon. Don’t worry. They’ll take good care of you.”

Mama did not lean over and kiss me on the forehead, and she did not hug me. She simply turned and left.

“See ya later, alligator,” I said. Without trying really, Mama had taught me how to take shelter behind my insecurities and just push on through the hard things in life without too much thought. In doing so, she taught me how to shut down emotionally, how to be just like her.

After she left, I went back to reading my book. A technician came in and drew my blood. Shortly before 11 A.M., a nurse came in and gave me my first ever IV drip, along with a shot that she claimed would help relax me. Then an orderly came and wheeled me on a gurney to the operating room. On the way, we passed a room where I saw a mother cradling her newborn.

The surgery room was freezing.

“Would you like a warm blanket?” a nurse asked.

“Yes,” I said. I couldn’t believe how cold it was. I felt like I was in a meat-market refrigerator. I wouldn’t have been surprised to see slabs of meat, curing and hanging from the ceiling’s corners.

Dr. Whitefield came in and sat on a stool as a nurse positioned my feet into stirrups. “Honey, I need you to scoot down just a bit to the edge of the table,” the nurse said. I edged my rump to the table’s end. Dr. Whitfield wheeled his seat over so he could look me in the eyes.

“We’re going to give you something to put you to sleep in just a minute,” he said. “You might hear a loud noise. Don’t be frightened. This machine is like a vacuum.” He pointed to a large round canister at the foot of the table. “We use it to clean out your uterus. This won’t take long. You’re going to be just fine.”

Too terrified to say anything in response, I simply nodded.

Dr. Whitfield reached up and patted my forearm. “You okay, Karen?”

“Yes, sir,” I lied.

The anesthesiologist asked me to lift my head so he could wrap a mask over face.

“How long will it take for me to fall asleep?” I asked.

“Not long,” he replied as he slipped the mask over my face. “Start counting to one hundred.”

I don’t remember anything after twenty-five.

I slept most of the rest of the day. The next day, around noon, Dr. Whitfield released me. He told me to expect bleeding and cramping for the next couple of weeks. He told Mama to call him immediately if I ran a temperature or had any clotting.

We drove home in silence. I stayed out of school the rest of that week. Wesley didn’t send flowers or come by the house to check on me, and neither did his mother.

_____

Many years later I felt compelled to tell my brother that I was wrong not to heed his advice. I’ve never enjoyed admitting that Frank is right about anything, but time had passed, and my attitude about my own abortion changed when I cradled my firstborn and realized what it meant to give life to another.

Frank was bouncing Konnie, the youngest of my four children, on his lap. I laughed as my eight-month-old daughter yanked on his fuzzy beard. Later, as he walked me to my car and helped load Konnie into her car seat, I turned to my brother. “I need to ask your forgiveness for something,” I said.

Frank leaned up against the door to my Toyota and crossed his arms over his barrel chest. “I’m listening,” he said.

“I’m sorry I had that abortion,” I said. “I wish I’d listened to you. But I was angry with you. I didn’t think you had any right to tell me what to do with my life. I was wrong. You were right.”

“I made mistakes, too, Karen,” Frank said. “I messed a lot of things up. I understand why you were angry with me. I don’t blame you for being mad.”

Then, he reached over and wrapped me up in a big bear hug. Forgiveness is something our family has learned to embrace. We’ve had to.