I once held F. Scott Fitzgerald’s battered leather briefcase in my trembling hands.

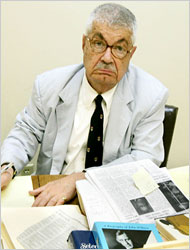

“Most libraries are showrooms. This place is a mess. This is my workroom,” said Dr. Matthew J. Bruccoli. It was the spring of 2005 and the preeminent F. Scott Fitzgerald scholar and collector was giving me a guided tour at the University of South Carolina’s Thomas Cooper library, where the good professor was working to catalog his impressive collection.

In 1947, Bruccoli was a teen driving around the Bronx when he heard Fitzgerald’s short story A Diamond as Big as the Ritz over the car radio. I think he said the car was a Dodge. That was all it took. The young teen wasted no time in tracking down a copy of The Great Gatsby. Thus, began his life-long curiosity and devotion to one of America’s most captivating writers. Bruccoli, who had retained his Bronx accent and attitude over the years, could be an imposing figure. He kept his hair shorn like a Marine and spoke brusquely, like he was in a hurry but, wait, there is one more thing that you must hear first, are you listening?

“I was an avid reader at the time and all I ever cared about was books,” Bruccoli said. “I’ve squandered my life, my fortune, and my property on gawd-damn books. Fitzgerald followed me through my life. If I could hit, I would have been playing center-field for the Yankees.”

Bruccoli bought Fitzgerald’s briefcase at auction. He paid $10,000 he did not have to keep the briefcase out of the hands of the second-highest bidder, a man Bruccoli didn’t like very much.

It was his great luck to become friends with Scottie Fitzgerald, the only child of F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald.

“Meeting her changed everything,” he said. “Scottie would walk right up to people as though she was going to kiss them. She cared more about performing acts of generosity than anyone I know. I was very, very lucky to have known her. But I never understood why she liked me. Her principal interests were in politics, especially Democratic politics. Scottie was never concerned by my utter indifference to politics and political activity.”

Bruccoli and Scottie collaborated on a book, The Romantic Egotists – a compilation that is part memoir and part family scrapbook.

“Oh. Gawd. Zelda,” Bruccoli declared. What he didn’t say but his tone conveyed: What. A. Mess. Bless. Her. Heart. “She did not have the literary genes that F. Scott possessed. She had sad, sad genes,” he said.

But even the talented and hard-working have to catch a break in the literary business. F. Scott’s came as a result of war. Critics had dissed the Great Gatsby. Sales were sluggish. Until the military picked it up.

“One-hundred and fifty-five-thousands copies of the Great Gatsby were given away to kids who were going to war – kids who never had heard of F. Scott Fitzgerald. Kids who were bored out of their wits. The complete book, not a digest,” Bruccoli explained.

The Armed Services edition put good literature in the hands of soldiers. Over 120 million books were handed out to men and women headed to war.

Can you imagine a One Book One Military Read? In essence, that became the role of the Great Gatsby during World War II.

When he died in 2008, Bruccoli gifted his Fitzgerald collection to the University of South Carolina. It’s estimated value is $4 million.

At the end of his own life, Fitzgerald was haunted by the sense that he was a failure as a writer, as a husband, as a father and as man. He discounted his own worth.

You ever find yourself doing that?

You too can visit the Fitzgerald collection at the USC library.

#30DaysofThankfulness: Do something purposeful. Help bring clean water to others. Click here.

#Day3: Thankful for those who see the value in us that we fail to see in ourselves.

Quote: “In any case you mustn’t confuse a single failure with a final defeat.” Fitzgerald/Tender is the Night