This book is by Jonathan Bernier (PhD, McMaster University) assistant professor of New Testament at Regis College, University of Toronto. It is entitled Rethinking the Dates of the New Testament: The Evidence for Early Composition (Baker Academic, 2022). And it is a game changer. How so?

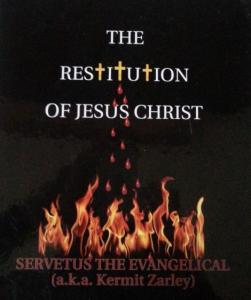

The dating of New Testament books and letters has some affect on deciding whether or not the New Testament identifies Jesus as God. I did a 28-year study on the subject of Jesus’ identity and then published a 600-page book on it, citing over 400 scholars. It is entitled The Restitution of Jesus Christ (2008), and I show that the New Testament does not ever identify Jesus as “God.” Yet I was a Trinitarian Christian for 22 years before I made this extremely important change in my christology and theology proper. So-called “orthodox Christianity” says I am no longer a Christian because of that. Rather, it deems me “a heretic.” I beg to differ, and this Bernier book somewhat supports my position even though he himself remains a Trinitarian Christian.

The dating of New Testament literature went through a serious re-examination by especially historical-critical Bible scholars beginning in the latter part of the nineteenth century. It started especially with the ad hoc History of Religions School which was centered in Germany. Most of the best academic study of the Bible was conducted in two centers in the world following the Protestant Reformation: The Vatican and Germany. Eventually, the United Kingdom entered that picture and the U.S. somewhat in the twentieth century.

But the History of Religions School, which lasted from about 1880 to 1920, was king in determining the dates of origin of New Testament books and letters. But some of these determinations by these historical-critical scholars were affected by their christology. They believed there was an extended time period in which Christians went from believing Jesus was Savior and Lord and born of a virgin, yet no more than a man, to believing that he was both man and God.

Among Christian literature, the earliest documents that clearly say Jesus is “God” are the seven letters of Ignatius, written in either 110 AD or 117 AD. And they repeatedly state this most unambiguously. Ignatius of Loyola claimed to be the bishop of Antioch. Prior to 70 AD, Antioch had become one of the two main centers of the early Jesus Movement with Jerusalem being the other one (e.g., Acts 11). For we read that “it was in Antioch that the disciples were first called Christians” (Acts 11.26 NRSV). Antioch was located just outside Israel in Syria, thus in Gentile land.

During the latter part of the second century and all of the third century, church fathers increasingly identified Jesus as “God” as can be seen in their preserved writings. However, these “apologists” as they were so identified, which means “defenders of the faith,” were clear in distinguishing Jesus’ divinity or godness as lesser in quality than that of the God whom Jesus worshipped. The New Testament shows that Jesus clearly and often called God “my Father.”

Thus, all of these church fathers distinguished between Jesus as the Son of God and that God whom Jesus worshipped. The Hebrew Bible (Old Testament) identifies God by name as yhwh, which most modern scholars translate as Yahweh. I refer to this apologist belief of the second and third century as “big God, little god,” meaning God the Father is the big God, and Jesus is the little god. Sometimes, it was stated similarly. Origin, generally recognized as the most academically astute church father of the third century, wrote multiple times that Jesus is “a second god.” And Philo identified the Logos as the same.

So, it was not until the the fourth century that the Catholic Church addressed officially the question of Jesus’ divinity. The so-called First Ecumenical Council of Nicea was held in 325 AD which was both called and officiated by the Roman Emperor Constantine. He demanded that the 318 bishops who attended the event, held over a period of weeks, conclude their deliberations by producing a public document which would state the nature of Jesus’ divinity. They did; it was called the Nicene Creed; and says Jesus is “very God of very God.”

This strange language to us moderns was borrowed from Greek philosophy. All 318 bishops spoke Greek because they were from the Eastern branch of the Roman Empire (no Latins attended from the Western branch of the empire). It meant that Jesus is just as much God as God the Father is God. Afterwards, many people, including especially religious Jews, accused Catholic Christians of believing in two Gods. The Catholic Church held its Second Ecumenical Council in Constantinople in 381 AD. It also was presided over by the Roman Emperor, and that is where the Catholic Church doctrine of the Trinity was made official even though the word “Trinity” was not used in its creed, which was an amplified Nicene Creed.

So, all historians and Christian scholars agree that there was a lengthy period of development in the Christian view of God and Jesus, a period of about 250 years. The best history book about this fourth century development is by R. P. C. Hanson entitled The Search for the Christian Doctrine of God: The Arian Controversy, 318-381.

In light of this historical development of the identity of Jesus in the second through the fourth century, historical-critical Bible scholars beginning especially in the nineteenth century claimed that certain New Testament documents had to have been written later than had been thought in order to allow time for Christians to change their view from thinking Jesus was no more than a man to him being both fully God and fully man.

Most of these historical-critical scholars alleged that the first three gospels of the New Testament, called synoptics, did not say Jesus was God whereas the Gospel of John clearly and repeatedly does. Even most conservative scholars believed the same. These liberal, historical-critical scholars then appealed to their belief about the necessary time period that it took Christians to change their view about Jesus’ identity and used that partisan belief in determining the dates of origin of the four New Testament gospels. This resulted in them deciding that the three synoptics were written well before the Gospel of John. Most decided that the synoptics were written in the 70s and 80s, but the Gospel of John was written some time during the second century, thus after the letters of Ignatius.

But in the twentieth century, this belief by historical-critical scholars–that the Gospel of John was written many decades after the synoptics were written–declined in the academy until hardly any scholars believe that today. Rather, the prevailing view among New Testament (NT) scholars of all stripes, including most historical-critical scholars, is that the Gospel of John was written during the 90s, more precisely probably in the late 90s; Mark was written in the 70s, and Luke was written in the 80s.

But Bernier’s new book seeks to overthrow all of that by claiming that all NT documents were written prior to 70 AD. That was the year the Roman armies ended the First Jewish Revolt (66-70 AD) by besieging Jerusalem and then destroying the place, including the temple. Bernier has the facts to back up his case. He also stands upon the work of one of my favorite NT scholars–John A. T. Robinson. He generally is regarded as one of the two most accomplished NT scholars of the United Kingdom in the twentieth century.

Robinson wrote two books on this subject. I have them in my library. I’ve marked them up so much that most people would probably think I’ve absolutely ruined those books. They are entitled Redating the New Testament and The Priority of John.

So, both Robinson and Bernier convincingly assert that all NT docs were written before 70 AD. I firmly believe this and treat it briefly in my book, The Restitution of Jesus Christ. In doing so, I often cite and quote Robinson. I haven’t read Bernier’s book yet, but it apparently is an improvement on Robinson’s work on this subject. The main evidence that the NT indicates that all of its docs were written prior to the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 AD is that they often mention Jerusalem and never say that it had been destroyed.

However, Robinson gets it right, and Bernier does not, on how this early dating of especially the Gospel of John supports the view that it does not claim anywhere that Jesus is God. This is what both the historical-critics and conservative Bible scholars get wrong–in my opinion and that of Robinson–that the Gospel of John does not identify Jesus as God, and an early origin of its date suggest as much. That is, it did take time for Christians to change from believing Jesus was not God to believing that he was God, and that time, contrary to Larry Hurtado, had to been many decades, thus into the second century.

[The Restitution of Jesus Christ is sold out. I expect it to become available this summer at amazon.com as an e-book and perhaps as a printed book. To view a list of about 150 posts that represent condensations of this book, click Christology in the menu bar on my blog’s home page. These posts usually focus on a particular scripture that traditionalists/Trinitarians assert indicate that Jesus is God, such as Isaiah 9.6; John 1.1c; 10.30; 20.28; Romans 9.5; Titus 2.13; Hebrew 1.8; 1 John 5.20.]

[The Restitution of Jesus Christ is sold out. I expect it to become available this summer at amazon.com as an e-book and perhaps as a printed book. To view a list of about 150 posts that represent condensations of this book, click Christology in the menu bar on my blog’s home page. These posts usually focus on a particular scripture that traditionalists/Trinitarians assert indicate that Jesus is God, such as Isaiah 9.6; John 1.1c; 10.30; 20.28; Romans 9.5; Titus 2.13; Hebrew 1.8; 1 John 5.20.]