I love my city. My family’s bones are here, laid across the plains, generation upon generation. Street names in North Canterbury bear record of my family’s presence. My mother’s ancestors, like those of many others’, were settler pioneers who found their way here from England, Ireland, Wales, and Germany, never to return. They left traces of themselves across the countryside and across the city that only a trained and familial eye could recognise. It’s a beautiful city with a wonderful heart and I have always felt very much a Cantabrian, viscerally linked to this place and to these people.

I love my city. My family’s bones are here, laid across the plains, generation upon generation. Street names in North Canterbury bear record of my family’s presence. My mother’s ancestors, like those of many others’, were settler pioneers who found their way here from England, Ireland, Wales, and Germany, never to return. They left traces of themselves across the countryside and across the city that only a trained and familial eye could recognise. It’s a beautiful city with a wonderful heart and I have always felt very much a Cantabrian, viscerally linked to this place and to these people.

I thought that when I was younger I would go away forever and live somewhere else, where my life would begin again, fresh and new. I thought how wonderful it would be to live in a place where everything didn’t have a memory. But I’m always drawn home. When I’ve been away for however long it’s a relief to feel my feet light on this place. I know its contours, its people, its smells, its rhythms, its humour, its heat, its cold, its winds, its houses and churches, its trees, its schools, its stories. And one year on, I know its pain.

February 22nd 2011 at 12:51pm. Everyone who was here has their story, and will

recall it with clarity. The twins were in a preschool at the University, I had a son on the East side of town at high school he had only just begun, three sons were up at school in North Canterbury, Nathan was at his office in town, and I was with 70 primary teacher education students at Rehua Marae.

I was in the dining room setting up some learning activities for after lunch. The ringawera were busy, the food smelled good, and looked delicious. I was starving and salivating at the salads, pies, savouries, rolls, fruit and desserts that seemed to pouring out of the kitchen. No marae does better food than Rehua.

We had no warning. There were no noises to tell us it was on its way. It literally assailed us with an inexplicable violence. The noise was deafening. It wasn’t just the rumble of the earth as she readjusted herself, it was the jack hammer that had so suddenly appeared underneath us, pounding our underside with abandon. We, and everything about us were thrown to the ground in a cacophony of splinters, thuds and screams. The building didn’t sway, it jumped and stamped and tantrumed and all I remember thinking was, ‘O God, please let my family be OK.’

Nathan was my first thought. Between aftershocks I had to scramble to find the phone, being thrown off my feet in a second wave of shaking as I reached behind the piano where it fell. The phones were momentarily down. A few minutes later a blessed text came,

‘Are you OK?’.

‘Yes’, I replied as I worked through a plan for the retrieval of the children.

‘Please get the twins’. I asked.

Minutes later his text found his way through the fug of others similarly reaching out for loved ones.

‘I can’t, I’m helping people who are trapped.’

I knew it was bad, but before the TV camera’s get there it’s hard to gauge the general fall out of a natural disaster. His revelation that things were dire sent a shudder of panic through me. There is a kind of crying that people do when they are beyond tears. It’s a moan that captures all of the grief, the dread, the fear and the sadness, and sends it up in an inexplicable wail.

‘No, no, no…’ were the words that went along with this cry.

The marae buildings were still standing. They looked the worse for wear. Miraculously the wharenui had only just emptied of the 70 plus who were literally minutes before, sitting around the walls. The two remaining had to scramble for safety otherwise there may have been injuries from a falling pou and the shattering of the front window. We were, at least physically, OK. Tamara, Amosa and I found our students, we formed a circle, prayed together on the marae atea and I told them to go home, ‘Now’.

Amidst a cacophony of sound coming from the CBD only a few blocks away I left to find my family. I don’t know why, but when in a panic, orienting oneself is very difficult, so I turned left and made my way North along Springfield Road. Liquefaction was spilling out onto the street and stunned residents were standing in the front gardens watching with incredulity as the road filled with the sticky, wet dark grey mud that would eventually render many homes uninhabitable as they sunk or were buried in the sludge. I switched on National Radio. 1:10pm Jim Mora was chatting merrily to someone in Taupo about their favourite song.

‘Word has come in from Christchurch that there has been an aftershock… but lets go to our next guest in Paraparaumu….’ He continued momentarily oblivious.

I turned left onto St Albans Street. By this time Jim was better informed. He began using words like,

‘Massive, devastating, horrific…’

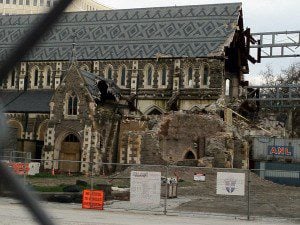

My slow pace meant that people on the street could walk beside me as I drove slowly along listening to the news at it came in. We didn’t need to say much to each other. ‘6.3’ seemed to suffice. I got to Papanui Road but couldn’t turn right. The brick masonry from St Mary’s church and the Merivale shopping precinct had shattered across the road. A woman was standing in the intersection holding a jacket directing everyone to turn left. She caught my eye as I went by and looked at me with a tenderness I will never forget.

‘People have died,’ came the realization.

Navigating streets filled with liquefaction, debris and cars took some time but upon arriving back at the University I was relieved that all of the buildings were still standing. People were everywhere. Huddled together under blankets, hugging each other, wandering aimlessly. Those I knew came to the car door as I made my way along University Drive. We held each other’s hands momentarily, we asked each other if we were OK but though we nodded that we were fine, one look at our ashen faces and our fearful eyes betrayed the real story. Nevertheless we needed to touch each other and to feel each other’s aliveness, and to take comfort in someone else’s physical proximity.

I found the twins sitting out on the car park eating yoghurt with their fabulous early childhood teachers telling stories, and singing songs. It made me weep at the goodness of those incredible and selfless teachers.

‘We made a turtle mum… and the ground was jumping’. They were excited to tell me.

It was somewhat reminiscent of their innovative game the day after the September 4th earthquake six months before.

‘What are you playing boys?’ I asked as they tore up and down the stairs throwing themselves under blankets and beds.

‘We’re playing aftershock’, they announced with enthusiasm.

As I set off up to Tuahiwi to pick up the other three, word came in that buses in town were crushed by falling buildings. The PPTA had held a stop work meeting at 12:30 in town and I knew that Isaac would be in transit somewhere between Linwood and the city. But he is a serial cell phone misplacer and I was punishing his fecklessness by not replacing the last one he lost. There was no way to get hold of him. ‘Oh Shit, please, please, don’t let it be Isaac’.

People are good. And the people in my city are outstanding. Paora Winitana bought my children home from Tuahiwi and took them to their place to play, oblivious to the havoc around them. Isaac was indeed on a bus in town when it struck. He was literally two minutes away from the collapsed Cashel Street that took the lives of so many. His bus came to a shuddering stop, he saw the pillars of dust billowing from the crumbled buildings and thought it was a planned implosive demolition. He made his way through the broken, shattered and wrecked inner city, walking from Barbadoes Street through the debris to Christ’s College. This is a journey he still won’t talk about. He found his friends and sat with them recovering. He found a cell phone and called Nathan to pick him up. It took 5 hours to put our family back together at home again.

Unlike others, our home was fine. I was surprised. I had lost one wine glass and had to pick up a portrait of one of the children that had fallen off the book case. But others were not so lucky. They came home to houses that they would never live in again or an emptiness left by someone who had gone – or both.

In the weeks that followed, life as we knew it ceased. A round of funerals had us farewelling good people who were just in the wrong place at the wrong time. There were those whose incredible generosity, hard work and kindness were a miracle for individuals and families.

I can’t explain or catalogue the incalculable changes that a 30 second earthquake caused in Christchurch, but there are some things I’ve learned over the past year:

- The earth has a mind of her own and she is an unpredictable mistress.

- To say that someone who escaped death was miraculously saved by the hand of God is cruel, and sinful and makes a mockery of God’s unremitting love for all.

- People are generous and kind. They are also resilient and resourceful and will find a way to smile again, or to make you smile again.

- Everyone has their own way of dealing with disaster. Some crawl away and try to disappear for a time, and some will show unusual strength and capacity in these conexts. You’ll not know what kind of reaction you will have until disaster strikes. Either is normal and natural.

- Ecclesiastical leadership might fail in times of disaster for personal, work related or emotional reasons – so don’t sit on your hands waiting for it because it might not come immediately. Take the initiative and show leadership or accept it in others.

- Church’s who aren’t beholden to a centralizing authority, who control the purse strings locally, did outstanding things and performed incredible service to their communities. Those of us who had to wait for people in other cities to respond , it was a exercise in frustration.

- Have an emergency or disaster preparedness strategy.

And so, a year on I still love my city but this time with a greater passion than even before. The earthquake has left its scars, but it has also left us with a story of a community that has dug deeper than a few brazen bellows at a rugby game. We’ve seen each other’s pain, and have walked with each other in our personal tragedies, and there is something intensely intimate and comforting in being with people who understand. That is why Christchurch will always be home.

He mauharatanga tēnei ki ngā mate kua mate i te ngāoko o Ruaumoko. Haere, haere, haere atu rā ki tua atu i te arai. Tāria atu kia tutuki mai tātou i ngā waewae o tō tātou kaiwhakaora, Ko Ihu Karaiti.