Giving God a Story, 2: The second of five posts on Elizabeth Johnson’s Quest for the Living God, Chapter 10, on the Trinity.

Elizabeth Johnson in Quest for the Living God joins a chorus in modern theology, starting in the last century, which has called for revitalizing Christian thinking about the Trinity. She wants that thinking to run in a different direction from what it has done in the not so long ago past. Then we started with the one perfect God in heaven. From that perfection theologians tried to find a way to a trinity of persons. Johnson insists on starting with the ways people have experienced God. She has in mind God’s involvement with the first Christians and their Hebrew ancestors.

In different ways the Christians and their elders, the Hebrews, experienced being saved. Johnson thinks if we start there then the Trinity will enter more than superficially into our faith lives. It will be more than repeating the Sign of the Cross and making ourselves believe three in one. Her first step in this program is to show us how the Church arrived at the doctrine of the Trinity.

Beginning with the experience of salvation

Salvation for the early Church

… was an encounter with Jesus Christ, whose life, death, and risen presence in the Spirit made tangible God’s gracious mercy poured out in the midst of sin and suffering…. Salvation is the experience without which there would be no talk of Trinity at all.” (p. 204)

That experience was captured in words that preceded any explicit Trinity doctrine. Early on, certainly before the Gospel we call Matthew, written in the 80’s, Christians baptized with the words

… in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. (Matthew 28:29)

Perhaps still earlier Christians greeted each other with the formula Paul gives us, writing in the 50’s:

The grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, the love of God, and the communion of the Holy Spirit be with all of you. (2 Corinthians 13:14)

The first Christians had a three-fold experience of salvation, and they couldn’t help applying that experience to their belief in the one God of the Jews. They were, after all, still Jews.

Controversy about Jesus and the Nicene Creed

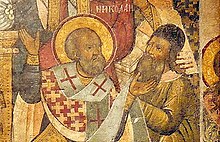

Around the year 112 Pliny the Younger, a Roman governor, wrote to the emperor to get counsel on the matter of Christians. They were refusing to worship the empire’s gods and, instead, were singing songs to Jesus “as to a God.” No doubt that practice factored into the rejection of Jesus by the majority of Jews and expulsion of Christians from the synagogue. But the divinity of Jesus wasn’t a settled matter for a while yet.

Early in the fourth century the Egyptian priest Arius made a sensible claim about Jesus. The one Christians knew, since the fourth Gospel, as the pre-existent Word was actually a creature. Made before there was a world, it was the highest of God’s creation. Arius said the man Jesus, our savior, was the incarnation of this less than divine being.

The Church had to reflect more explicitly and theologically about what it meant to be saved. Specifically, through the long tradition beginning in Israel, it was God who saved. To deny that Jesus is God was to deny the Christian experience of salvation in Jesus. It made the references to Jesus and the Spirit in the cherished Baptism formula out of place. (p. 205)

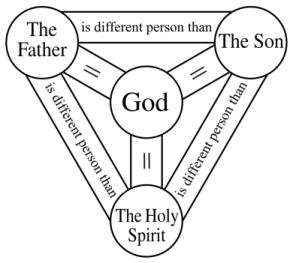

The bishops, meeting at Nicaea in 325, condemned Arius and agreed on a first version of the Nicene Creed. It was a triple statement of belief – in “one God the Father,” in “one Lord Jesus Christ,” and in “the Holy Spirit.” This Creed amplified the section about Jesus to make his divinity clear. Jesus is “the Son of God … very God of very God, begotten, not made, being of one substance with the Father.” There was as yet no similarly expanded account of the divinity of the Holy Spirit. Another council in Constantinople in 381 made up for that omission. The Holy Spirit is one “who proceeds from the Father, who with the Father and the Son together is worshiped and glorified.” (Quotes are from “Nicene Creed” in Theopedia.)

Theology becoming more abstract

Nicene and Constantinople didn’t explain how God could be one and three. They simply affirmed that this was the belief of the Church from the beginning. Better, perhaps, this was the three-fold way the Church experienced being saved, interpreting now with Greek thought categories. More detailed descriptions (not explanations) followed with Eastern and Western patterns differing. Both divisions of the Church sought “to illuminate the faith that the creed confesses.” (p. 206)

This story eventually started going downhill. Theologians imagined two Trinities. There was an “economic Trinity” — God active in a three-person way in time in the “economy” of salvation. But God also existed eternally in absolute freedom, including the freedom to create or not create a world. With a separate name, the “immanent Trinity,” it raised the issue of the connection of one part of God’s life with the other. Medieval scholars, like Thomas Aquinas, separated God into different books. They discussed the one God (De Deo Uno), then the Trinity (De Deo Trino), then salvation, God’s involvement in the world.

Increasingly separated from prayer and sacramental life, the doctrine [of the Trinity] lost its footing in the religious experience of salvation and began to become something complicated and elite. (p. 207)

Enlightenment Era influence on theology

I remember from seminary theology classes a distinction between revealed theology and natural theology. Natural theology came first. By heroic effort and your own natural reasoning powers, you should be able to prove God’s existence. This would be one God, all-good, all-powerful, but with no hint of a unity of three persons. Then comes revealed or biblical theology, where God makes things easier for us. The Bible reaffirms God’s existence and includes things that we couldn’t otherwise know, like the Incarnation and the Trinity.

It was an approach to God typical of the Enlightenment Era. Find out what human reason can tell you about God. In a rationalistic age that seemed to be the best way to anchor the faith. Then see what the Bible says in addition. But don’t stay too long with the Bible. Rather, let human reason loose again on the Bible’s three-person God. The Trinity turned into, in Johnson’s words, “an afterthought … an appendage to the basic doctrine of God. [The doctrine] became philosophically abstract, saying little if anything about salvation.” (p. 207)

Theology turns around.

I remember a high (or low) point of abstract thought about the Trinity. Karl Rahner in the 1960’s called it “a more or less foregone conclusion.” Any one of the three Persons in the Trinity could have become incarnate as the savior of humanity. (The Trinity, p. 11) Father, Son, and Spirit had their distinct lives in their divine communion, however exciting (or not) that might be. But those distinctions made no difference to us. I don’t know how anyone could think we needed to believe something so irrelevant. It made a marvelous test of faith, though.

Karl Rahner counters:

The Trinity is a mystery of salvation, otherwise it would never have been revealed.

He follows up this statement with what Johnson calls a rule for theologizing about the Trinity:

The “economic” Trinity is the “immanent” Trinity and the “immanent” Trinity is the “economic” Trinity. (The Trinity, p. 21-22, emphasis original)

I interpret: God didn’t need a world in any of the ways that human beings need things – to be happy, to be fulfilled, to feel useful. God could have been perfectly happy in the community of infinite love scholars call the immanent Trinity. Still from all eternity God has made the free decision to create a world. It’s a decision to forever be in relation to what is not God. The infinite, eternal God commits God’s self to finite, temporal creation. God takes on responsibilities, even burdens in an emotional story with tragic elements, the economy of salvation. The immanent Trinity has always been the economic Trinity by God’s free choice.

One way or another trinitarian theology has had to deal with Rahner’s insight. Thinking about the Trinity, even the so-called immanent Trinity, can’t proceed very long apart from the doctrine and experience of God’s saving work.