The text arrived while I sat at a coffee shop bent over a lazy notebook and a blank page. Happy Mother’s Day, the text read. Thank you for taking care of us. I can only imagine how stressful it was. I hope you’re doing well.

My head jerked back as I sucked in caffeinated air. I sat in my chair for approximately three seconds before I retreated to the bathroom to cry. I continued bawling on the way home. Later while in the shower, I moaned like an animal as the water attempted to wash away my grief and sadness.

I have found myself trying to avoid this aspect of my past during the two-and-a-half years since I left my marriage. There are many things that I freely share about my decision to leave Zalmay, my ex-husband. I have never discussed how much I fear that I failed as a mother.

**

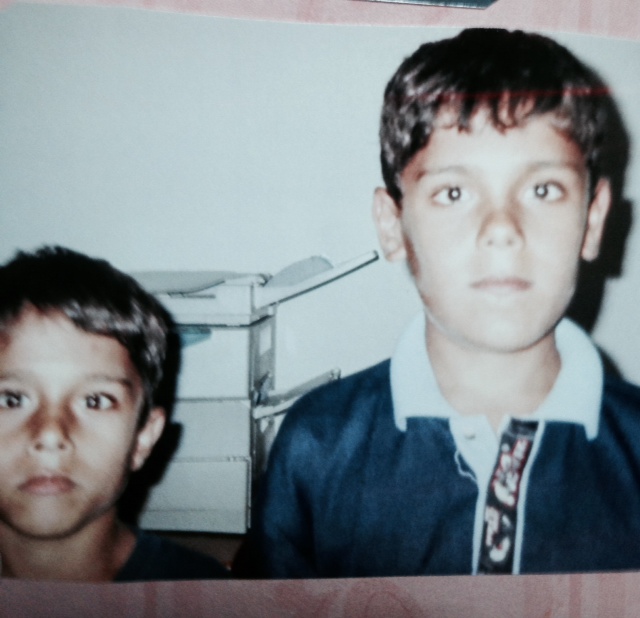

The text came from my stepson, Mujtaba. He is one of the five stepchildren I raised during my marriage; one of two who witnessed the final, confusing years of the relationship. He and his brother, Jamal, are now in college and live two miles from me.

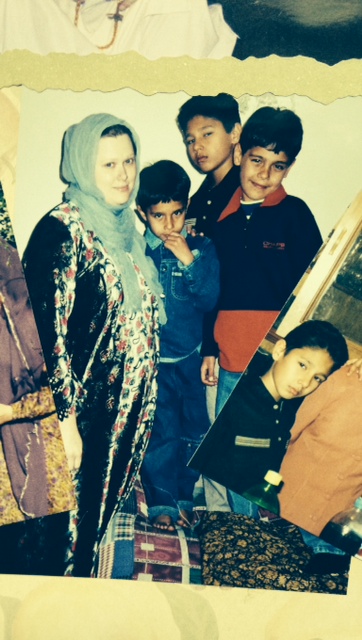

Only occasionally, and perhaps when I am trying to shock or impress people, do I mention that I raised five stepchildren plus the son I had with my ex-husband during my marriage, making a total of six kids that fell under my care. I managed a full tribe as we moved around the world and back: Washington D.C., then Azerbaijan, New York City, then the Middle East. Plus, there was the yearly trek to Pakistan where Zalmay’s family lived as middle-class refugees.

I had stowed the motherhood part of myself away post-divorce (Ibrahim, my biological son, being the exception) because I did not know how to assign meaning to the experience. To be fair, I felt I had nothing positive to say.

Here is the untidy, painful truth: I never felt joy in the constant drudgery of raising so many children, particularly with the burden of moving internationally several times during the marriage. I consistently felt overburdened with enforcing Zalmay’s unrealistic values where I felt I could never freely talk with them about the things I wanted to discuss: faith, identity, love, sex, and general existence. There were many anecdotes from my own life I silenced because I understood that my stories would contradict Zalmay’s version of reality.

The discussions we did have regarding matters of faith and being in the world were jovial, yet they always ended with the following edicts: just don’t eat it, just don’t do it, just try not to think it.

My Islam fell into glorious shades of gray. Yet, once I married, I never fought for my right remain in that ethereal place. I also felt that I had no place to fight for my stepchildren’s right to own theirs, even though my experience as an American-Muslim would end up being closer to theirs as first generation Afghan-Americans.

I kept my stories silent and arrived in the marriage almost as an ahistorical persona. Likewise, Zalmay never shared too many his more complicated personal stories with the children, either. These narratives could have opened space for increased familial love and respect. Instead, these unspoken stories functioned as a deficit; things that remained silent for the sake of someone else’s comfort.

Zalmay never shared at length how he spent his teenage years fighting with the mujahedeen against the Soviets, or how he once smuggled the mother of a mujahedeen leader out of Afghanistan during the Taleban’s early days. He never said a word about the mysterious pictures I once found of him laying on a bed with a bloody head in the company of concerned men. I sensed that Zalmay kept his amazing stories secret, telling me only bits and pieces, and never telling his children much at all. They have grown up knowing a kind yet emotionally detached father who was unyielding in matters of faith.

Zalmay did not have a normal adolescence, even by Afghan standards. The war against the Soviets disrupted “real life” for his generation. He was the eldest son and therefore inherited adult responsibility for the family at a young age, particularly when they relocated to Kabul from their village. At twelve years old, he was the one enrolling his younger siblings in school. By the time he was sixteen years old, he spent his summers fighting the Soviets. He would grow up to successfully – and impressively — manage complex global realities to benefit larger humanity. Yet, in truth, he had little preparation for relating to the complexities of his first-generation, American-Muslim children. This was one area where I had the advantage. I failed to own it. And in the name of ownership, Zalmay has never told his children about his role in Afghan history and his current place in global society.

During our marriage, these untold stories hovered between us like ghosts.

**

I have avoided writing and talking about my stepchildren. When I do speak of them, I find myself saying, “my ex-step-children,” but I sense a deep injustice when uttering that statement. One day, I will have another husband, God willing. But I am burdened with the knowledge that my stepchildren are now college age and that they will never have another mother. Perhaps it isn’t too late for me to reclaim some of what I failed to give them during my marriage. Perhaps now I can show up and be an unfiltered friend and mentor.

Zalmay sometimes suggested that I had failed as parent because I could not make the children perfect and fault-free. I internalized this failure as evidence of my own inadequacies; One must be truly flawed to mess up motherhood, to hate the task of it all, I often thought. On the surface, Zalmay admitted that people made mistakes and that no one was perfect, him included. But little room existed for the nuanced experiences that arrive from the act of living. Who could possibly make six children perfect? Were they not allowed their own doubts and journeys of self-discovery?

Tell me, I now want to say, where is the handbook for blended families burdened by geopolitical dynamics beyond what most families experience?

Tell me, now I want to say, what was I supposed to do with immigrant children whose birth mother had beaten them and subjected them to emotional abuse?

Tell me, I now want to say to Zalmay, how come you never acknowledged all the ways I did succeed as a mother? Can you not see how we collectively failed these children?

Zalmay was never unkind to me or to his children, yet his expectations were so high that we all consistently felt inadequate. We could never measure up. I understand that Zalmay held such standards out of love. He wanted everyone and everything to be OK. He did not know another way to parent. His cultural norms suggested that the failure of one reflected on us all. He was scared of losing control of his family during his prolonged absences and in the vast space of the world we inhabited.

Zalmay did not understand that his emotional vulnerability and intimacy in front of his children was permissible, even desirable; that in showing his children his humanity, he could have made them more self-confident in their own. Perhaps the most painful part is that I forfeited the experience of joy in raising these children because I gave up my right to claim my own truth. I did not fight for myself in this regard and I failed, in return, to fight for their right to claim their experiences as valid.

**

When I fled the marriage, I desired a complete absolution of my parental responsibilities regarding my stepchildren. I wanted little do to with them because they represented how I had failed myself. Therefore, I spent two years barely talking about this aspect of my life. I had minimal contact with Mujtaba and Jamal, even though they had just started a college down the street.

In my post-divorce world, I tried to recreate the bohemian culture of my early twenties filled with artsy folks living in an economic bracket far below what I had experienced with Zalmay. I subconsciously sought to get far away from the the mountains of responsibility I had inherited in my marriage. I sometimes found myself thinking how the experience of parenting so many children now seemed lost; virtually undetectable in my current persona. Where did it go?

I can only imagine how stressful it was. I hope you’re doing well, Mujtaba wrote to me on Mother’s Day. My abandoned stepson could speak a truth that his father had missed. Perhaps now was time to shed such ghosts and to show up for this part of my story.

I texted Mujtaba back: Let’s meet for dinner sometime soon.

________

Deonna Kelli Sayed is a Love, Inshallah contributor and a www.patheos.com/blogs/loveinshallah editor. She is a published author and an emerging digital storyteller. Her work is also found ataltmuslimah.com, Muslimah Media Watch, and storyandchai. Deonna is currently working on a memoir with support a Regional Artist Grant from the North Carolina United Arts Council. To learn more, visit her website, and join her on Facebook and Twitter.

Deonna Kelli Sayed is a Love, Inshallah contributor and a www.patheos.com/blogs/loveinshallah editor. She is a published author and an emerging digital storyteller. Her work is also found ataltmuslimah.com, Muslimah Media Watch, and storyandchai. Deonna is currently working on a memoir with support a Regional Artist Grant from the North Carolina United Arts Council. To learn more, visit her website, and join her on Facebook and Twitter.