A Voice in the Wind, pp. 13-22

Last week we began our series on Francine Rivers’ historical Christian fiction novel, A Voice in the Wind. We met Hadassah, a young Christian girl trapped in Jerusalem during the First Jewish-Roman War. I noted two primary things last week—first, that it is extremely unlikely that a Christian girl would find herself in Jerusalem during this period, given that most Christians fled the city when the war broke out; and second, that Hadassah’s father, with a wife and three children to think of, shouldn’t have gone out to preach to those trapped in the city with them, putting his life on the line.

When Hadassah tries to stop her father from going out in the city, her mother chides her and accuses her of stoping like Satan. Hadassah’s fear is also portrayed as a problem—indeed, as Rivers lays out her character, her fear is one of the most important components of it. And that fear is linked to doubt. As I noted, Hadassah’s fear is perfectly understandable—she’s in the middle of a brutal war zone, after all! That fear plays a central role in this next section—the fall of Jerusalem.

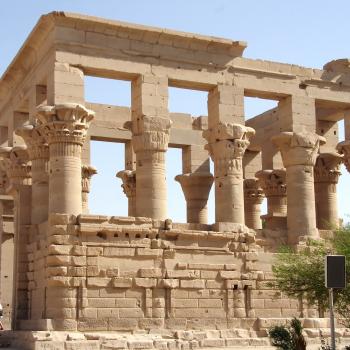

The battle is raging within the walls, now. Hadassah and her mother, brother, and sister are hiding in the small house they rented in Jerusalem, for their Christian passover visits. Rivers details the battle between the Romans and the zealots within the city itself—the fighting at Antonia Tower, and at the Court of the Gentiles, and at the Mount of Olives. The Romans crucified the zealots they captured there. But it was not over.

Stillness fell again. And then a new, more devastating horror spread through the city as word passed of a starving woman who had eaten her own child. The flame of Roman hatred was fanned into a blaze.

Here Rivers is relying on Josephus. There’s more detail in Josephus’ telling, though—the woman was starving, yes, but she also sought to horrify the “seditious varlets” who had been stealing from her by killing her child and offering them its body. In other words, she was upset with the Jewish defenders of the city, and sought to make a point in killing and eating her child—at least as Josephus tells it. When the Romans heard about this, Josephus tells us, some “could not believe it” and “others pitied the distress which the Jews were under” but many of them “were hereby induced to a more bitter hatred than ordinary against our nation.” Still relying on Josephus, Rivers describes the Jews luring the Romans into the temple, and then setting it on fire. Titus ordered the fire put out, and again again they were attacked.

This time all the officers of Rome couldn’t restrain the fury of the Roman legionnaires who, driven by a lust for Jewish blood, once again torched the temple and killed every human being in their path as they began plundering the conquered city.

Josephus writes that “Caesar was no way able to restrain the enthusiastic fury of the soldiers” and that he did not want the temple burned down and ordered those around him “beat the soldiers that were refractory with their staves, and to restrain them” but was unsuccessful because “their passions too hard for the regards they had for Caesar … as was their hatred of the Jews, and a certain vehement inclination to fight them.” In addition, Josephus says, “the hope of plunder induced many to go on.” And so the sack of the city began.

Hadassah could hear the screams from the house where she hid with her family. Her mother died “the same hot August day that Jerusalem fell” and still the children sat there for two days, alone, listening to the screams of death. Finally, she can hear someone coming. She hears a barked order to search the houses. Mark stands by the door, waiting. A soldier enters and runs him through.

Tertius gripped his sword harder and glared down at the emaciated young girl covering an even smaller girl. He ought to kill them both and have done with it! These bloody Jews were a blight to Rome. Eating their own children! Destroy the women and there would be no more warriors birthed. This nation deserved annihilation. He should just kill them and be done with it.

But of course, he doesn’t. As he glared at Hadassah “something about her” stopped him from acting. He sees her mother, laid out for burial, looking peaceful, as though asleep.

He had heard the story of the woman eating her own child and it had fed his hatred of the Jews, gained from ten long years in Judea. He had wanted nothing more than to obliterate them from the face of the earth. They had been nothing but trouble to Roman from the beginning—rebellious and proud, unwilling to bed to anything but their one true god.

Rivers tells us that Tertius had been “driven by bloodlust” and had relished each death as he went through the fallen Jerusalem killing those he found. Tertius tries to figure out why he’s hesitating from killing Hadassah and Leah, both of whom are completely silent, waiting. He’s not sure. Ultimately Tertius grabs the two and drags them to the Women’s Court, where the other captives have been gathered. All of this is accompanied by rich description of the sack of the city, and the cries of the captives.

Hadassah found a place by a wall to sit, and held Leah. In the morning, her sister was dead. She looked peaceful at last. A soldier saw the girl and took her from Hadassah, who was too weak to stop him. For days Hadassah sat there, alone, and for days more died. Finally, food was brought in, but Hadassah wasn’t given any, as she was so weak the soldiers distributing the corn believed she would soon die, and did not want to waste it.

One day the whole crowd of captives was taken outside the walls to watch a ceremony. Titus, gave a speech and then presented awards to his soldiers and officers.

Hadassah looked around at her fellows and saw their bitter hatred; having to witness this ceremony poured salt in their open wounds.

Finally it comes time to feed the captives again, and this time, after a hurried prayer, Hadassah manages to obtain food—a scoop of corn kernels.

She could almost hear her mother’s voice. “The Lord will provide.”

We’ll get back to that in a moment.

Before eating the corn in her hands, Hadassah prayed.

“Oh, Father, forgive me. Amend my ways. But gently, Lord, lest you reduce me to nothing. I am afraid. Father, I am so afraid. Preserve me by the strength of your arm.”

Finally, Hadassah feels a sense of peace—and of God’s nearness.

The night was warm … she had eaten … she would live. “God always leaves a remnant,” Mark had said. Of all the members of her family, her faith was weakest, her spirit the most doubting and the least bold. Of all of them, she was least worthy.

“Why me, Lord?” she asked, weeping softly. “Why mean?”

Okay, let’s talk about this.

Note the obvious contrast between the “bitter hatred” of the Jews around Hadassah and Hadassah’s humility before God. When Hadassah receives food, she remembers her mother’s words—“The Lord will provide”—despite the fact that God most certainly did not prevent her mother, father, brother, or sister from dying—two by the sword, and two by starvation.

To some extent, we choose our response to traumatic or difficult events. If we lose a job, we can focus on anger with the person or events that led to this loss, or we can view it as a positive time for reevaluating various career or job paths and landing back on our feet. This is sometimes referred to as “the power of positive self-talk.” While we can’t always control the situations we’re in, we can shape our response. Just the other day a family outing didn’t go exactly as I’d planned, but as I started to become upset I realized that I could accept the adjustments and enjoy an outing that wasn’t exactly as I’d envisioned it, or I could spend the entire outing in a funk and have a bad memory on top of it. I chose option A.

It’s interesting, religion and psychology are often seen as completely separate fields, but they’re not as unrelated as one might think. Evangelical authors, theologians, and pastors frequently portray “bitterness” as something bad to be avoided, and their definition of the term is frequently expansive. Instead of holding onto anger, evangelicals are supposed to accept what life brings them and remember that God will never give them more than they can handle—and that God works all things together for good. But sometimes holding onto anger is important—it can be necessary to create change—and sometimes accepting what life brings and looking for the good in it can make it easy for others to take advantage of you.

Additionally, in a world still rife with anti-semitism, I worry about Rivers’ portrayal of the Jews in this section: She describes Jewish people who have just watched their city taken and their friends and families slaughtered as having “bitter hatred” and contrasts this with the gentle acceptance and hopefulness of a young Christian girl. I assume Rivers believes that in portraying the anti-semitism of the Roman troops she is being sympathetic to the Jewish situation, but she undercuts this in her portrayal of the Jews’ response to their situation—“bitter hatred.” This is not how people are supposed to respond to persecution, after all, in the evangelical world. Love those who hate you, evangelicals say, and pray for those who persecute you. The Christian girl is being accepting and open to God; the Jewish people are being bitter and full of hatred.

I’m curious whether Rivers spent time researching what the various strands of Judaism at the time taught about persecution, or about responding to being wronged. I suspect there’s a lot more going on here historically than “bitter hatred” that Rivers isn’t taking the time to explore. This is tied up in a fundamental underlying problem in the way evangelicals approach Judaism. On the one hand, they believe the Jews will play a special role in the end times and they view them as a special people. On the other hand, they believe the Jews missed their own messiah, they spend little time trying to understand Jewish belief and practice, and they can play into anti-semitic tropes without being cognizant of it. I suspect there will be more of this to unpack as this book goes on.

Before I bring this section to an end, I want you to notice something else, too. Rivers’ frequent portrayal of Hadassah as an individual with weak faith is going to become a staple in this book. It’s one of her defining characteristics. Note that Hadassah begins her prayer by asking God to forgive her. Hadassah has just lived through the deaths of her father, mother, brother, and sister, and has seen unimaginable horrors while being carried through the city (Rivers is quite graphic in describing crucifixions, bloated rotting bodies, and the stench of blood that covered the city). And yet, when Hadassah finally prays, she asks God to forgive her. She’s not angry. She’s sorry. She believes she is in the wrong, for her weak faith.

This is perhaps illustrative of a distinction between Judaism and evangelicalism. In my understanding, Jews are encouraged to talk back to and question God. Evangelicals are not. Hadassah’s tendency to question God is, in the evangelical understanding, a serious fault. You don’t question God. You accept his will for you, whether you understand it or not, period. And you know what? I remember being afraid my faith was weak. I remember torturing myself over it. Why couldn’t I be more outspoken? Did it mean my faith was weak? Why couldn’t I do more? Why didn’t God suffuse every moment of my life? Was I not trying hard enough? Not believing hard enough?

Poor Hadassah, to lose her family so brutally and so young, and yet to belong to a faith that makes her feel so insecure and so often at-fault.