Voice in the Wind, pp. 341-343

Hadassah is meeting again with the group of Christians she met recently. Asyncritus is preaching to the rest.

“Ours is a struggle to live a godly life in a fleshly world. We must remember we are not called upon by God to make society a better place to live. We are not called upon to gain political influence, nor to preserve the Roman way of life. God has called us to a higher mission, that of bringing to all mankind the Good News that our Redeemer has come…”

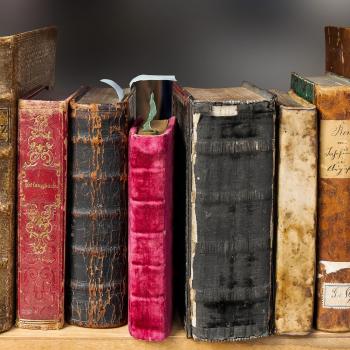

Several years have gone by since this book began; we are now at around 75 AD. By this time scholars believe Mark had been written, but not Matthew, Luke, or John. About half of the various books and epistles that comprise the remainder of the New Testament had been written by this time as well; the others were yet to be written. The term “redeemer” does not appear in any New Testament book. Early Christianity was a time of flux, and of great diversity of belief. Key doctrines (such as the divinity of Jesus) were still being worked out.

Suffice it to say, Rivers is writing like a modern evangelical, and not like an early Christian. The earliest Christians believed that the end of the world was eminent. That was, after all, what Jesus had preached—that this generation would not pass away before all was accomplished, that the son of man would return like a thief in the night and they must be prepared. Why is none of this evident in Hadassah’s faith, or in that of the Christian group she has found? The focus is on sharing the gospel, but without the impetus of the imminent end of the world.

But this isn’t all. Even the idea of what salvation meant was in question. Today we often think of “substitutionary atonement” as the core of Christianity, but the idea was not born overnight. Here’s a sermon by Paul in Athens as an example of early Christian rhetoric:

Acts 17:22-31

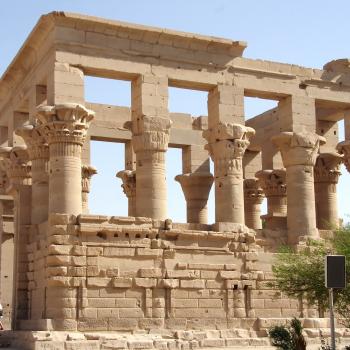

22 So Paul stood in the midst of the Areopagus and said, “Men of Athens, I observe that you are very religious in all respects. 23 For while I was passing through and examining the objects of your worship, I also found an altar with this inscription, ‘TO AN UNKNOWN GOD.’ Therefore what you worship in ignorance, this I proclaim to you.

24 The God who made the world and all things in it, since He is Lord of heaven and earth, does not dwell in temples made with hands; 25 nor is He served by human hands, as though He needed anything, since He Himself gives to all people life and breath and all things; 26 and He made from one manevery nation of mankind to live on all the face of the earth, having determined theirappointed times and the boundaries of their habitation, 27 that they would seek God, if perhaps they might grope for Him and find Him, though He is not far from each one of us; 28 for in Him we live and move and exist, as even some of your own poets have said, ‘For we also are His children.’ 29 Being then the children of God, we ought not to think that the Divine Nature is like gold or silver or stone, an image formed by the art and thought of man.

30 Therefore having overlooked the times of ignorance, God is now declaring to men that all people everywhere should repent, 31 because He has fixed a day in which He will judge the world in righteousness through a Man whom He has appointed, having furnished proof to all men by raising Him from the dead.”

Here’s another example, also from Acts:

Acts 10:34-43

34 Then Peter began to speak: “I now realize how true it is that God does not show favoritism 35 but accepts from every nation the one who fears him and does what is right. 36 You know the message God sent to the people of Israel, announcing the good news of peace through Jesus Christ, who is Lord of all. 37 You know what has happened throughout the province of Judea, beginning in Galilee after the baptism that John preached— 38 how God anointed Jesus of Nazareth with the Holy Spirit and power, and how he went around doing good and healing all who were under the power of the devil, because God was with him.

39 “We are witnesses of everything he did in the country of the Jews and in Jerusalem. They killed him by hanging him on a cross, 40 but God raised him from the dead on the third day and caused him to be seen. 41 He was not seen by all the people, but by witnesses whom God had already chosen—by us who ate and drank with him after he rose from the dead. 42 He commanded us to preach to the people and to testify that he is the one whom God appointed as judge of the living and the dead. 43 All the prophets testify about him that everyone who believes in him receives forgiveness of sins through his name.”

And here is how Hebrews, likely written in the early 60s, begins:

Hebrews 1:1-4

God, after He spoke long ago to the fathers in the prophets in many portions and in many ways, 2 in these last days has spoken to us in His Son, whom He appointed heir of all things, through whom also He made the world. 3 And He is the radiance of His glory and the exact representation of His nature, and upholds all things by the word of His power. When He had made purification of sins, He sat down at the right hand of the Majesty on high, 4 having become as much better than the angels, as He has inherited a more excellent name than they.

Can you see how different this sounds from modern evangelicalism—and from the beliefs Rivers has been attributing to Hadassah? I’d be interested in reading a book about early Christians that handled all of this in a period appropriate way, with an accurate understanding of the beliefs and development of early Christianity, but this book is not that book.

But this—this next part—is what got me as a teen:

Bowing her head, Hadassah closed her eyes and prayed for the Lord’s forgiveness. She was ashamed. She had brought the Good News to no one. When opportunities presented themselves, she shied away from them in fear. Her master and mistress asked her to tell them about God, and she had cloaked the truth within a parable. She should have told them about Jesus, of his death on a cross, of his resurrection, of his promises to all who believed in him.

This absolutely tortured me. And seriously? She doesn’t need this! Her family was killed in front of her, she was taken halfway across the world in chains, and then sold as a slave. And here she’s torturing herself for not preaching her religion to her master and mistress (note that her fellow slaves, prime targets for proselytization, are again not mentioned). But these sorts of things made me feel personally indicted myself as an evangelical teen—why didn’t I preach the gospel to everyone I met, from the library to the grocery store?

Why were the Valerians so obsessed with unimportant things? A week didn’t pass that she didn’t hear Marcus and Decimus arguing politics and business. “The national budget must be balanced and the public debt reduced!” Decimus insisted; Marcus argued that the authorities had too much control and must be limited. Decimus blamed Rome’s problems on the imbalance of foreign trade, saying the Roman people had forgotten how to work and had become content to live on public assistance.

This sounds very American. I’m curious whether people at the time were in fact saying things like this, or whether Rivers didn’t bother cracking a book to read about economic and social critiques levied against the empire in the 70s AD (and I’m sure there were many).

When Hadassah arrives home, Marcus is waiting for her. His father had mentioned the events of the other day, when Hadassah had told them the parable of the prodigal son, and “all the pieces of the puzzle fell into place” for Marcus. Hadassah was a Christian. And of course, hands Marcus being hands, the scene begins with this:

She slipped silently inside the side door of the villa’s gardens and lowered the bar again. She hurried along the pathway and entered the back of the house. She closed the door quietly, then gasped as a strong hand caught hold of her arm and spun her around.

Awesome. Marcus demands to know where she has been and gets her to confess to being a Christian. It takes more handiness, of course.

“Aren’t you going to deny it?” he demanded roughly.

She lowered her head. “No, my lord,” she said very softly.

He jerked her chin up. “Do you know what I could do to you for being a member of a religion that preaches anarchy? I could have you killed.”

Marcus’s constant physical handling of the women in his life makes me hella uncomfortable. This constant jerking women around and grabbing them is a way of asserting dominance and establishing that he is in control.

But let’s get back to the whole “I could have you killed” thing. [As readers have pointed out, Marcus have her killed anyway—she’s a slave. She’s not his slave, so he’d probably get in trouble with his dad, or with Caius, whoever technically owns her, but it would be over destruction of property, not murder].

“We don’t preach anarchy, my lord.”

“No? What would you call it when your religion demands you obey your god above an emperor?”

And there’s this, from near the end of the passage:

A scene came back to him of a dozen men and women tied to pillars and drenched in pitch, screaming as they were set aflame, acting as torches for Nero’s circus. Shuddering, Marcus drained his goblet.

Earlier in this review series, I discussed scholarly questions over whether the persecution of Christians under Nero actually took place.

It seems we have no contemporary sources that say anything about Nero blaming the Christians for the fire in 64. There are contemporary sources on the fire, yes, but none of them mention Nero blaming the Christians. Tacitus is the first source to do so, and he wrote his Annals around 116, over fifty years later. Historians writing after him appear to have gotten the claim from Tacitus, but we do not have any information on where Tacitus might have gotten the claim himself. Even biographies of Nero written contemporaneously with Tacitus do not mention Nero blaming the fire on the Christians.

There’s another problem of course, which I also covered in that earlier post—the term “Christian” was not widely used among Christians until the 90s, and we find the first use of the term in non-Christian sources in the 110s. Marcus would not have known the term, and Hadassah would not have used it to describe herself. Paul’s letters, remember, aren’t addressed “to the Christians at X place.” Instead they’re addressed “To the church of God which is at Corinth with all the saints who are throughout Achaia” or “To all the saints in Christ Jesus who are in Philippi.”

If Nero did persecute the Christians, it was likely an isolated incident, as scholars believe the periodic persecutions of Christians during this time did not get under way until the 80s or later. Systemic, empire-wide persecutions did not occur until the third century, nearly two hundred years after Hadassah’s time.

If Nero did persecute the Christians, the official charge was arson, not their faith. They were scapegoats. This contrasts with Marcus’ claim that Christians were killed for preaching “anarchy.” Here is what Tacitus said about the incident, writing fifty years after it occurred:

But all human efforts, all the lavish gifts of the emperor, and the propitiations of the gods, did not banish the sinister belief that the conflagration was the result of an order. Consequently, to get rid of the report, Nero fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations, called “Chrestians” by the populace.

This is, by the way, one reasons one scholars doubt the reliability of Tacitus’ account; the Roman people in the 60s AD would not have used the label “Christian.” By Tacitus’ day the term was known, of course, so it’s possible he was simply back-attributing the use of a label he was familiar with in his present time. Still, that suggests that the passage of time, and his knowledge in his own period, have shaped his telling of this story.

Accordingly, an arrest was first made of all who pleaded guilty; then, upon their information, an immense multitude was convicted, not so much of the crime of firing the city, as of hatred against mankind. Mockery of every sort was added to their deaths. Covered with the skins of beasts, they were torn by dogs and perished, or were nailed to crosses, or were doomed to the flames and burnt, to serve as a nightly illumination, when daylight had expired.

Interestingly, Tacitus suggests that Christians were persecuted under Nero not simply for arson but also for “hatred against mankind.” This is different from what Rivers has put in Marcus’ mouth—that Christians were accused of anarchy because they obeyed their God over the emperor. The allegations made against Christians were not as open-and-shut as Rivers’ reference to anarchy would suggest. In the second century, after all, Christians were accused of cannibalism, of holding orgies, and of murdering babies.

Most of the early Christian persecution discussed in the New Testament involves struggles within Judaism. Read the end of Acts. When the Jews seize Paul to kill him, the Roman commander in the area, hearing that the region is in confusion, comes in and removes him from their custody. “Wanting to ascertain the charge for which they were accusing him, I brought him down to their Council,” this commander wrote to the local governor, “and I found him to be accused over questions about their Law, but [under no accusation deserving death or imprisonment.” The commander sends him to the governor to make a determination.

Acts 25:23-27

23 So, on the next day when Agrippa came together with Bernice amid great pomp, and entered the auditorium accompanied by the commanders and the prominent men of the city, at the command of Festus, Paul was brought in.24 Festus *said, “King Agrippa, and all you gentlemen here present with us, you see this man about whom all the people of the Jews appealed to me, both at Jerusalem and here, loudly declaring that he ought not to live any longer. 25 But I found that he had committed nothing worthy of death; and since he himself appealed to the Emperor, I decided to send him. 26 Yet I have nothing definite about him to write to my lord. Therefore I have brought him before you all and especially before you, King Agrippa, so that after the investigation has taken place, I may have something to write. 27 For it seems absurd to me in sending a prisoner, not to indicate also the charges against him.”

So they call Paul in to speak to them, which he does for twenty-nine verses.

Acts 26: 30-32

30 The king stood up and the governor and Bernice, and those who were sitting with them, 31 and when they had gone aside, they began talking to one another, saying, “This man is not doing anything worthy of death or imprisonment.”32 And Agrippa said to Festus, “This man might have been set free if he had not appealed to Caesar.”

Here is how Acts ends:

Acts 28:30-31

30 And he stayed [in Rome] two full years in his own rented quarters and was welcoming all who came to him, 31 preaching the kingdom of God and teaching concerning the Lord Jesus Christ with all openness, unhindered.

Paul was acquitted. Remember, he was only taken to Rome for trial because he asked to be taken to Rome for trial. The governor, Festus, wanted to set Paul free, finding the charges against him baseless. And remember, this was in the early 60s, ten years before Rivers set her book. It is of course possible that these accounts were sanitized as early Christianity became increasingly anti-semitic. Consider, for example, that each subsequently written gospel places less blame for Jesus’ death on Pilate, and more blame on the Jews. Still, it is unsurprising that the Romans, famously tolerant of religion, wouldn’t give early Christianity a second look, intervening only when conflicts over Christianity gave rise to unrest.

Outside of Tacitus’ writings, fifty years after the fact, about a persecution of Christians under Nero, the first official record we have of early Christian persecution comes from Pliny the Younger, who wrote to the Emperor Trajan in 112 for advice on a situation he was handling as governor of Bithynia. According to Robert Louis Wilkins in his book The Christians as the Romans Saw Them:

Shortly after Pliny’s arrival in the city, a group of local citizens approached him to complain about Christians living in the vicinity. What precisely the complaint was we do not know, but from several hints in the letter it is possible to infer that the charge was brought by local merchants, perhaps butchers and others engaged in the sale of sacrificial meat. Business was poor because people were not making sacrifices. … No doubt some trouble had arisen between Christians and other sin the city. This was unusual. In most areas of the Roman Empire Christians lived quietly and peaceably among their neighbors, conducting their affairs without disturbance. … Only in those places where friction existed were local magistrates inclined to bring charges against Christians or to initiate legal action.

Here is Pliny’s letter to Trajan:

It is my practice, my lord, to refer to you all matters concerning which I am in doubt. For who can better give guidance to my hesitation or inform my ignorance? I have never participated in trials of Christians. I therefore do not know what offenses it is the practice to punish or investigate, and to what extent. And I have been not a little hesitant as to whether there should be any distinction on account of age or no difference between the very young and the more mature; whether pardon is to be granted for repentance, or, if a man has once been a Christian, it does him no good to have ceased to be one; whether the name itself, even without offenses, or only the offenses associated with the name are to be punished.

Meanwhile, in the case of those who were denounced to me as Christians, I have observed the following procedure: I interrogated these as to whether they were Christians; those who confessed I interrogated a second and a third time, threatening them with punishment; those who persisted I ordered executed. For I had no doubt that, whatever the nature of their creed, stubbornness and inflexible obstinacy surely deserve to be punished. There were others possessed of the same folly; but because they were Roman citizens, I signed an order for them to be transferred to Rome.

Soon accusations spread, as usually happens, because of the proceedings going on, and several incidents occurred. An anonymous document was published containing the names of many persons. Those who denied that they were or had been Christians, when they invoked the gods in words dictated by me, offered prayer with incense and wine to your image, which I had ordered to be brought for this purpose together with statues of the gods, and moreover cursed Christ–none of which those who are really Christians, it is said, can be forced to do–these I thought should be discharged. Others named by the informer declared that they were Christians, but then denied it, asserting that they had been but had ceased to be, some three years before, others many years, some as much as twenty-five years. They all worshipped your image and the statues of the gods, and cursed Christ.

They asserted, however, that the sum and substance of their fault or error had been that they were accustomed to meet on a fixed day before dawn and sing responsively a hymn to Christ as to a god, and to bind themselves by oath, not to some crime, but not to commit fraud, theft, or adultery, not falsify their trust, nor to refuse to return a trust when called upon to do so. When this was over, it was their custom to depart and to assemble again to partake of food–but ordinary and innocent food. Even this, they affirmed, they had ceased to do after my edict by which, in accordance with your instructions, I had forbidden political associations. Accordingly, I judged it all the more necessary to find out what the truth was by torturing two female slaves who were called deaconesses. But I discovered nothing else but depraved, excessive superstition.

I therefore postponed the investigation and hastened to consult you. For the matter seemed to me to warrant consulting you, especially because of the number involved. For many persons of every age, every rank, and also of both sexes are and will be endangered. For the contagion of this superstition has spread not only to the cities but also to the villages and farms. But it seems possible to check and cure it. It is certainly quite clear that the temples, which had been almost deserted, have begun to be frequented, that the established religious rites, long neglected, are being resumed, and that from everywhere sacrificial animals are coming, for which until now very few purchasers could be found. Hence it is easy to imagine what a multitude of people can be reformed if an opportunity for repentance is afforded.

And here is Trajan’s response:

You observed proper procedure, my dear Pliny, in sifting the cases of those who had been denounced to you as Christians. For it is not possible to lay down any general rule to serve as a kind of fixed standard. They are not to be sought out; if they are denounced and proved guilty, they are to be punished, with this reservation, that whoever denies that he is a Christian and really proves it—that is, by worshiping our gods—even though he was under suspicion in the past, shall obtain pardon through repentance. But anonymously posted accusations ought to have no place in any prosecution. For this is both a dangerous kind of precedent and out of keeping with the spirit of our age.

And remember, this is 112 AD, quite some time after 75 AD, which is when Rivers’ story is currently set. Even so, Pliny is unfamiliar with Christianity, and with how to handle it. Trajan says not to go looking for Christians, and not to accept anonymous denunciations. This is typically what persecution of Christians looked like in the early second century—local people would accuse some among their population of being Christians (often for personal or economic reasons), and local officials would be called on to arbitrate the dispute.

Marcus’ claim that he could have Hadassah killed for being a Christian, in 75 AD, is idiosyncratic. Not only had the persecutions like the one in Bithynia in 112 not gotten into gear yet—only a decade before Paul had preached Christianity openly in the city, and he was still been acquitted of any crime—but even when persecutions like this did occur sporadically across the empire, Christians tended to be denounced for various interpersonal reasons. What cause would he have for denouncing Hadassah as a Christian?

Marcus isn’t done with Hadassah, and I was going to keep going and finish out this section. Alas, I’ve run out of time, and this post is long enough already. Next week we return to handsy Marcus and his confrontation with pious Hadassah.