Stepping Heavenward, chapter III, part 1

Today we enter a new chapter of Katy’s life.

Last week, we left Katy at her 17th birthday, in January, 1832. From time to time, Katy’s journal engages in some time jumping. Presumably, Katy just isn’t regular about writing, but since this is fiction, it ultimately serves the author’s purchase—it allows the author to include cover Katy’s entire life in a single volume, without including the minutia of every moment.

This week we pick up June, 1832.

My school-days are over! I have come off with flying colors, and mother is pleased at my success. I said to her today that I should now have time to draw and practice to my heart’s content.

“You will not find your heart content with either,” she said.

The woman does not let up.

Anyway, Amelia is by now such good friends Jane Underhill that Katy also has been thrown into her circles. Jane lends her novels, and I found it interesting to try to work out just what Prentiss was getting at in her discussion of these books. Is she for them, or against? Against, surely.

I wish I liked more solid reading; but I don’t. And I wish I were not so fond of novels; but I am. If it were not for mother I should read nothing else. And I am sure I often feel quite stirred up by a really good novel, and admire and want to imitate every high-minded, noble character it describes.

Katy, here, is trying to justify her novel reading. She argues that reading novels makes her want to “imitate every high-minded, noble character it describes.” In other words, novel reading is good for her, she argues.

But then we get this:

Jenny has a miniature of her brother “Charley” in a locket, which she always wears, and often shows me. According to her, he is exactly like the heroes I most admire in books.

We have come to the central theme of this chapter: Jane’s brother Charley. Katy’s introduction to Charley is Jane’s claim that he is “exactly like the heroes” Amelia loves in her novels. And here, Prentiss wants us to know, is the problem with novels. Jane’s brother Charley is selfish, shallow, self-serving cad—but he looks and acts all handsome and dashing, like in the novels, so Jane is all taken with him. Novels feed passion and feeling, and undermine common sense.

At least, that’s my take on what Prentiss is trying to say in this bit about novels.

Here’s the thing about Charley, though. I don’t think Katy falls for him quite as much because of the novels as Prentiss thinks. I think there’s something very different going on here.

Mother pointed out to me this evening two lines from a book she was reading, with a significant smile that said they described me:

“A frank, unchastened, generous creature, Whose faults and virtues stand in bold relief.”

“Dear me!” I said, “so then I have some virtues after all!”

And I really think I must have, for Jenny’s brother, who has come here for the sake of being near her, seems to like me very much.

Katy falls for Charley because he likes her, and thinks she’s amazing, when all she’s gotten from her mother is dour lectures on her faults. Note that when her mother says that passage describes her, Katy’s response is surprise that her mother thinks she has any virtues at all.

After being constantly lectured by her mother—her mother responds to her jubilation that she can draw and practice music to her heart’s content by telling her she won’t find her heart’s content there—is it really any wonder she falls for Charlie, who praises her and tells her she’s wonderful?

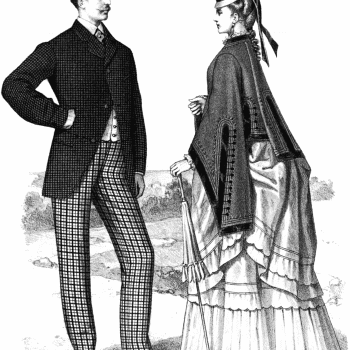

All through the summer, Katy’s interests are about Charley, who has “the most perfect manners” and “a great deal of feeling.” Katy generally sees Charley when her mother is away helping a woman in labor or otherwise occupied, which is certainly convenient.

By the end of the summer, Katy is writing things like this:

Jenny says her brother is perfectly fascinated with me, and that I must try to like him in return. I suppose mother would say my head was turned by my good fortune, but it is not. I am getting quite sober and serious. It is a great thing to be–to be–well–liked. I have seen some verses of his composition to-day that show that he is all heart and soul, and would make any sacrifice for one he loved. I could not like a man who did not possess such sentiments as his.

Perhaps mother would think I ought not to put such things into my journal.

As the summer draws to a close, Jenny, Amelia, and Katy hatch a plan—a plan that will keep them much in contact with Charley.

The plan is for us three girls, Jenny, Amelia and myself, to form ourselves into a little class to read and to study together. She says “Charley” will direct our readings and help us with our studies. It is perfectly delightful.

How very convenient.

Somehow I forgot to tell mother that Mr. Underhill was to be our teacher. So when it came my turn to have the class meet here, she was not quite pleased.

Oops. “Somehow I forgot” indeed.

Throughout this whole section, we are given only small hints that we should not like Charley. To be sure, there is Katy’s reticence to let her mother know what is going on. But what, other than that, do we have to tell us that Charley is a cad? Perhaps we are to assume that he wouldn’t agree to this little tutoring plan if he weren’t—perhaps we are to assume that no respectable young man of 19, who should be in business, would spend so much time closeting himself with girls of 17.

The first thing that concretely gives me pause is this:

The class met at Amelia’s to-night. Mother insisted on sending for me, though Mr. Underhill had proposed to see me home himself. So he stayed after I left. It was not quite the thing in him, for he must see that Amelia is absolutely crazy about him.

Katy is displeased that Charley stays at Amelia’s after she leaves, because Amelia is crazy about him, and Katy is pretty sure it is to her that his interests are directed. Charley seems to go out of his way to spend a lot of time with his younger sister’s fresh and lively friends, both of whom are—totally coincidently, of course—completely besotted with him.

In Little Women, Laurie is both an orphan boy and the heir of his grandfather’s vast fortune, just as Charley is. Like Charley does with Katy and Amelia, Laurie spends a lot of time with the book’s protagonists, the March sisters. Laurie is, of course, younger Charley—he is only 15 when the book opens—but rumors fly around very quickly that pair his name with that of Meg March.

Of course, Laurie spends time with the March girls because he is lonely, and because he enjoys their lively and imaginative play. He takes roles in the plays the girls put on, and joins their secret society, becoming a contributing member to the Pickwick Papers. And the March girls are not besotted with him.

In just a moment, we’re going to have another opportunity for comparison between the two books. Remember the conversation Marmee has with Meg and Jo after the ball where Meg first overhears speculation linking her name with Laurie’s? Well, when Katy’s mother first realizes Katy’s name is being linked to Charley’s, she gives Katy a similar—and completely different—lecture.

But first, there’s this:

We met at Jenny’s this evening. Amelia had a bad headache and could not come. Jenny idled over her lessons, and at last took a book and began to read. I studied awhile with Mr. Underhill. At last he said, scribbling something on a bit of paper:

“Here is a sentence I hope you can translate.”

I took it, and read these words:

“You are the brightest, prettiest, most warm-hearted little thing in the world. And I love you more than tongue can tell. You must love me in the same way.”

We are quite clearly meant to take this as a definite sign that Charley is a cad. He should not be saying such things to Amelia without first talking to her mother, and without making his intentions clear. To switch continents but stay in the same period, I’m getting some Mr. Wickham vibes.

I’m having a hard time evaluating these actions outside of the cultural norms in which they are ensconced. Charley is two years older than Amelia, so perhaps we could imagine a college sophomore returning home on break to hit on his younger sister’s high school senior friends. I get the distinct feeling that Charley surely has something else he should be focusing on—a career, or his guy friends—but then, lots of men of this era married their younger sister’s friends.

Perhaps the easiest comparison to make is to other literature from the period, and when I compare Charley’s actions to Jane Austen novels, again, he’s definitely pinging Wickham. Spending this much largely unchaperoned time with vulnerable young women, flattering them with his praises and attentions and basking in their near-worship—that’s a sign of trouble, in Austen novels.

It is the next morning that Katy’s mother finally clues in. It is September 29th, and the lessons have been going on for a month.

“Kate, I do not like these lessons of yours. At your age, with your judgment quite unformed, it is not proper that you should spend so much time with a young man.

“Jenny is always there, and Amelia,” I replied.

“That makes no difference. I wish the whole thing stopped. I do not know what I have been thinking of to let it go on so long.

…

I began to cry.

“He likes me,” I got out, “he likes me ever so much. Nobody ever was so kind to me before. Nobody ever said such nice things to me. And I don’t want such horrid things said about him.”

“Has it really come this!” said mother, quite shocked. “Oh, my poor child, how my selfish sorrow has made me neglect you.”

I kept on crying.

“Is it possible,” she went on, “that with your good sense, and the education you have had, you are captivated by this mere boy?”

“He is not a boy,” I said. “He is a man. He is twenty years old; or at least he will be on the fifteenth of next October.”

“The child actually keeps his birthdays!” cried mother. “Oh, my wicked, shameful carelessness.”

“It’s done now,” I said, desperately. “It is too late to help it now.”

“You don’t mean that he has dared to say anything without consulting me?” asked mother. “And you have allowed it! Oh, Katherine!”

And that’s it. That’s really it.

So, let’s recap. Katy’s mother expresses disbelief that she could possibly be besotted with Charley, because she has too much “good sense” for that. Super helpful, mom! Katy’s mother refers to her as “the child.” Nowhere does Katy’s mother take her into her confidence, or attempt the reverse. Nothing in this would make me ever want to tell my mother about anything.

As far as I can see, we are not meant to see Katy’s mother as a bad mother. On the contrary. Throughout the books he is held up as a role model and a paragon of virtue. Even Katy wishes she could pray with her mother’s zeal, that she could have her mother’s contentment, etc. Katy’s mother is supposed to be a good mother. Her mistake, here, was in not monitoring Katy more closely.

Let’s contrast this to a similar scene in Little Women. When Meg is sixteen, she goes away to the Moffats’ house for a week, and dances at balls and engages in all manners of romps. When she returns home, she feels ashamed of some of her behavior—she feels that it was frippery and excess—and she goes to Marmee to confess her follies. Her sister Jo, who is fifteen, is in the room as well.

“Marmee, I want to ‘fess’.”

“I thought so. What is it, dear?”

“Shall I go away?” asked Jo discreetly.

“Of course not. Don’t I always tell you everything? I was ashamed to speak of it before the younger children, but I want you to know all the dreadful things I did at the Moffats’.”

“We are prepared,” said Mrs. March, smiling but looking a little anxious.

“I told you they dressed me up, but I didn’t tell you that they powdered and squeezed and frizzled, and made me look like a fashion-plate. Laurie thought I wasn’t proper. I know he did, though he didn’t say so, and one man called me ‘a doll’. I knew it was silly, but they flattered me and said I was a beauty, and quantities of nonsense, so I let them make a fool of me.”

“Is that all?” asked Jo, as Mrs. March looked silently at the downcast face of her pretty daughter, and could not find it in her heart to blame her little follies.

“No, I drank champagne and romped and tried to flirt, and was altogether abominable,” said Meg self-reproachfully.

Note first how differently Marmee is responding to this than Katy’s mother would have, at such a confession. Katy’s mother would have been in full lecture mode, surely.

“There is something more, I think.” And Mrs. March smoothed the soft cheek, which suddenly grew rosy as Meg answered slowly…

“Yes. It’s very silly, but I want to tell it, because I hate to have people say and think such things about us and Laurie.”

Then she told the various bits of gossip she had heard at the Moffats’, and as she spoke, Jo saw her mother fold her lips tightly, as if ill pleased that such ideas should be put into Meg’s innocent mind.

The “various bits of gossip” were the assertions she overheard that Mrs. March surely had a “plan” for one of her girls and that wealthy Laurence boy, else why was she throwing her girls in his path?

The last time I read this passage, I remember being bothered by all of the insistence on how very innocent Meg’s mind was—and should be—and it still bothers me. Meg was sixteen. The idea that she should think nothing of boys or dating or any of that is absurd. It’s true that people did not marry quite as young back then as we often think they did, when we look back from today. But while Meg wouldn’t have been expected to marry yet for some years, she’s not eight.

There is little age difference between Meg, in this section, and Katy, in Stepping Heavenward. Somehow, Katy seems far more worldly wise than Meg. I’m not sure why this is.

Regardless, let’s return to Mrs. March and her girls. Jo has just exclaimed in anger at hearing the words Meg repeated, and has vowed to tell all of the Moffats that there are no such plans.

“No, never repeat that foolish gossip, and forget it as soon as you can,” said Mrs. March gravely. “I was very unwise to let you go among people of whom I know so little, kind, I dare say, but worldly, ill-bred, and full of these vulgar ideas about young people. I am more sorry than I can express for the mischief this visit may have done you, Meg.”

“Don’t be sorry, I won’t let it hurt me. I’ll forget all the bad and remember only the good, for I did enjoy a great deal, and thank you very much for letting me go. I’ll not be sentimental or dissatisfied, Mother. I know I’m a silly little girl, and I’ll stay with you till I’m fit to take care of myself. But it is nice to be praised and admired, and I can’t help saying I like it,” said Meg, looking half ashamed of the confession.

“That is perfectly natural, and quite harmless, if the liking does not become a passion and lead one to do foolish or unmaidenly things. Learn to know and value the praise which is worth having, and to excite the admiration of excellent people by being modest as well as pretty, Meg.”

I find myself conflicted, on reading Marmee’s words—that is, until I compare them to Katy’s mother’s words. Here, Marmee affirms Meg’s desire to be liked, and calls it natural and harmless. She cautions Meg against acting only to be liked, and suggests that she learn to identify “the praise which is worth having” and to gain admiration not just for being pretty but for other things as well. Compare this with Katy’s mother’s complete denunciation of Katy’s desire to be liked.

There’s something else that’s different here. Marmee is talking with her girls, not at them the way Katy’s mother does. When I read conversations between Katy and her mother, I can never get past the sense of distance I feel between them. Not so, when Marmee talks to her girls.

Finally, Marmee offers her girls these words:

“Mother, do you have ‘plans’, as Mrs. Moffat said?” asked Meg bashfully.

“Yes, my dear, I have a great many, all mothers do, but mine differ somewhat from Mrs. Moffat’s, I suspect. I will tell you some of them, for the time has come when a word may set this romantic little head and heart of yours right, on a very serious subject. You are young, Meg, but not too young to understand me, and mothers’ lips are the fittest to speak of such things to girls like you. Jo, your turn will come in time, perhaps, so listen to my ‘plans’ and help me carry them out, if they are good.”

Jo went and sat on one arm of the chair, looking as if she thought they were about to join in some very solemn affair. Holding a hand of each, and watching the two young faces wistfully, Mrs. March said, in her serious yet cheery way…

“I want my daughters to be beautiful, accomplished, and good. To be admired, loved, and respected. To have a happy youth, to be well and wisely married, and to lead useful, pleasant lives, with as little care and sorrow to try them as God sees fit to send. To be loved and chosen by a good man is the best and sweetest thing which can happen to a woman, and I sincerely hope my girls may know this beautiful experience. It is natural to think of it, Meg, right to hope and wait for it, and wise to prepare for it, so that when the happy time comes, you may feel ready for the duties and worthy of the joy. My dear girls, I am ambitious for you, but not to have you make a dash in the world, marry rich men merely because they are rich, or have splendid houses, which are not homes because love is wanting. Money is a needful and precious thing, and when well used, a noble thing, but I never want you to think it is the first or only prize to strive for. I’d rather see you poor men’s wives, if you were happy, beloved, contented, than queens on thrones, without self-respect and peace.”

“Poor girls don’t stand any chance, Belle says, unless they put themselves forward,” sighed Meg.

“Then we’ll be old maids,” said Jo stoutly.

“Right, Jo. Better be happy old maids than unhappy wives, or unmaidenly girls, running about to find husbands,” said Mrs. March decidedly. “Don’t be troubled, Meg, poverty seldom daunts a sincere lover. Some of the best and most honored women I know were poor girls, but so love-worthy that they were not allowed to be old maids. Leave these things to time. Make this home happy, so that you may be fit for homes of your own, if they are offered you, and contented here if they are not. One thing remember, my girls. Mother is always ready to be your confidant, Father to be your friend, and both of us hope and trust that our daughters, whether married or single, will be the pride and comfort of our lives.”

“We will, Marmee, we will!” cried both, with all their hearts, as she bade them good night.

Now, yes, Marmee was dealing with a different situation. Meg was not besotted, and Laurie, with whom her name had been connected, was a good boy, who had behaved himself only honorably. But had Katy’s mother ever had a conversation like this with her? This week is the first time in the book that boy trouble has come up, and we jump straight to Katy’s mother lecturing her angrily.

There is no invitation to be a confidant, no discussion of what qualities to look for in a suitor. Indeed, Katy’s mother rather sets the stage for conflict. She doesn’t listen to Katy or hear her out. When she lets Katy run on a bit about her feelings for Charley, her response is “Has it really come to this!” and “Is it possible that with your good sense, and the education you have had, you are captivated by this mere boy?” Way to make Katy feel like crap! Way to build walls between you!

Why would Katy ever come to her mother again, about anything, after this outburst? Sure, Katy is the one crying, but it is her mother who is giving into passion in her lecturing. “Oh, Katherine!”

Lord, such drama.

So there you have it. Today’s lesson on how not to talk to your daughter about boys. (And in case you’re wondering if Katy’s mother’s lecture worked, I won’t make you wait for next week—no, no it did not.)

I have a Patreon! Please support my writing!