Stepping Heavenward, Chapter XI part 2

I found this section interesting because it’s not something we generally have to deal with today. Today, we tend to live in nuclear family units. Unmarried sisters move into their own places, and older parents move into assisted living facilities. Not so in the 19th century.

In February, Ernest’s mother dies. Katy, we learn, has always assumed that her mother will come and live with them. Ernest goes to his family home, leaving Katy in New York City, where she receives some letters from her mother that make her conclude the time has come for her mother to move in with them. Her mother, she writes, misses her.

Just as soon as Ernest returns home I will ask him to let her come and live with us. I am sure he will; he loves her already, and now that his mother has gone he will find her a real comfort. I am sure she will only make our home the happier.

Oddly, Katy apparently never mentioned her assumption that her mother would come live with them to Ernest. Because, well—

FEB. 28 Such a dreadful thing is going to happen! I have cried and called myself names by turns all day. Ernest writes that it has been decided to give up the old homestead, and scatter the family about among the married sons and daughters. Our share is to be his father and his sister Martha, and he desires me to have two rooms got ready for them at once.

So all the glory and the beauty is snatched out of my married life at one swoop! And it is done by the hand I love best, and that I would not have believed could be so unkind. I am rent in pieces by conflicting emotions and passions.

One moment I am all tenderness and sympathy for poor Ernest, and ready to sacrifice everything for his pleasure. The next I am bitterly angry with him for disposing of all my happiness in this arbitrary way. If he had let me make common cause with him and share his interests with him, I know I am not so abominably selfish as to feel as I do now. But he forces two perfect strangers upon me and forever shuts our doors against my darling mother. For, of course, she cannot live with us if they do.

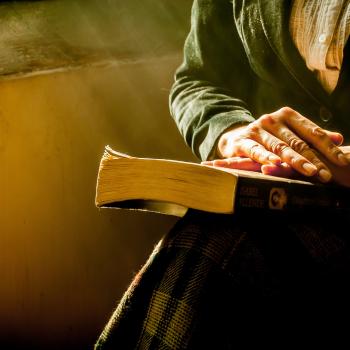

Katy goes through the motions, setting up the room she’d intended for her mother—moving in her stuffed chair, her writing table, and the good family Bible—and preparing it for her father-in-law instead. She is completely miserable as she does so.

Finally, Ernest arrives with his father and his sister, Martha.

I had got up a nice little supper for them, thinking they would need something substantial after their journey. And perhaps there was some vanity in the display of dainties that needed the mortification I felt at seeing my guests both push away their plates in apparent disgust. Ernest, too, looked annoyed, and expressed some regret that they could find nothing to tempt their appetites.

Martha said something about not expecting much from young housekeepers, which I inwardly resented, for the light, delicious bread had been sent by Aunty, together with other luxuries from her own table, and I knew they were not the handiwork of a young housekeeper, but of old Chloe, who had lived in her own and her mother’s family twenty years.

Martha is a terrible, terrible person.

Martha and Ernest’s father effectively turn the household upside down. They are both awful, completely dour, the opposite of Katy, and constantly critical of everything about Katy. Finally, it is all too much.

Yesterday I came home from an exhilarating walk, and a charming call at Aunty’s, and at the dinner-table gave a lively account of some of the children’s exploits. Nobody laughed, and nobody made any response, and after dinner Ernest took me aside, and said, kindly enough, but still said it,

“My little wife must be careful how she runs on in my father’s presence. He has a great deal of every thing that might be thought levity.”

Then all the vials of my wrath exploded and went off.

“Yes, I see how it is,” I cried, passionately. “You and your father and your sister have got a box about a foot square that you want to squeeze me into. I have seen it ever since they came. And I can tell you it will take more than three of you to do it. There was no harm in what I said-none, whatever. If you only married me for the sake of screwing me down and freezing me up, why didn’t you tell me so before it was too late?”

Ernest stood looking at me like one staring at a problem he had got to solve, and didn’t know where to begin.

“I am very sorry,” he said. “I thought you would be glad to have me give you this little hint. Of course I want you to appear your very best before my father and sister.”

Katy gives him what for. “My best self is my real self,” she tells him. She begins to cry and can’t stop.

If I could have told my troubles to some one I could thus have found vent for them, but there was no one to whom I had a right to speak of my husband.

This whole don’t talk to someone else about your husband thing bothers me, but while it’s definitely something Debi Pearl and her lot say, I don’t think it’s limited to them. Obviously, there needs to be a balance, but there is a difference between shit-talking and asking a trusted friend for a sanity check.

Ernest is pacing.

“This has come upon me like a thunderclap,” he said. “I did not know I kept your heart hungry. I did not know you wished your mother to live with us. And I took it for granted that my wife, with her high-toned, heroic character, would sustain me in every duty, and welcome my father and sister to our home. I do not know what I can do now. Shall I send them away?”

Oy.

Um.

Yeesh.

I’m not sure whether this is simply an Ernest is human moment, or whether it’s worth drawing out the bits in there that definitely look manipulative. Also, he should maybe stop taking his wife’s feelings for granted and start coming to her when making bit decisions.

Katy does not back down.

“You knew I had faults when you married me; I never tried to conceal them.”

And did you fancy I had none myself?” he asked.

“No,” I replied. “I saw no faults in you. Everybody said you were such a noble, good man and you spoke so beautifully one night at an evening meeting.”

Ouch. See okay this is part of the problem.

If you are planning to marry someone and you think they have no faults, you may want to consider the possibility that you should get to know them better before you go all in and marry them.

All of this feels very real, though, and Katy really is so young. If I’m counting right, she’s 21. I got married at her age too, and I was very young and had a lot to learn. When I look back from my vantage point today, my early years of marriage look littered with stupid fights over things that didn’t matter. In large part, we simply hadn’t yet learned how to effectively navigate disagreements, and instead hashed them out in ways that were ineffective, painful, and pointless.

Having recently reread Prentiss’ full book, I can tell you now that Katy and Ernest do get better at communicating. I think one thing that may appeal to evangelical women today about this book is that it portrays a marriage that is very messy at the beginning, in a way that feels very real and very familiar, as two individuals learn to live with each other and, over time, learn how to communicate and understand each other.

Some readers may feel that this book mirrors their own story, that it helps them better understand their journey, viewed in retrospect. Others may not be there yet—or may not ever arrive there, not every marriage does—and may approach the storyline with hope.

See, for instance, the realism in this passage:

“And now is it possible that you and I, a Christian man and a Christian woman, are going on and on with scenes as this? Are you to wear your very life out because I have not your frantic way of loving, and am I to be made wear of mine because I cannot satisfy you?”

“But, Ernest,” I said, “you used to satisfy me. Oh, how happy I was in those first days when we were always together; and you seemed so fond me!”

These two are very different people. Can they learn to understand and accommodate each other, over the gap of those differences?

“Katy,” he said, “if you can once make up your mind to the fact that I am an undemonstrative man, not all fire and fury and ecstasy as you are, yet loving you with all my heart, however it may seem, I think you will spare yourself much needless pain–and spare me, also.”

“But I want, you to be demonstrative,” I persisted.

“Then you must teach me.”

Ah, see. There it is. Some readers stuck in marriages that aren’t all happiness and roses may see some of their husbands’ faults or deficits in Ernest, and long for just this response. Then you must teach me.

And remember, this book is written in the 19th century. The more I read this book the more I wonder how much my fundamentalist upbringing shaped my understanding of gender relations in that decade—and not in ways that promoted historical accuracy.

“And about my father and sister, perhaps, we may find some way of relieving you by and by. Meanwhile, try to bear with the trouble they make, for my sake.”

And so their dispute ends—for now.

But see, there are still problems.

APRIL 3.-Martha is closeted with Ernest in his office day and night. They never give me the least hint of what is going on in these secret meetings. Then this morning Sarah, my good, faithful cook, bounced into my room to give warning. She said she could not live where there were, two mistresses giving contrary directions.

Clearly, all is not well here.

I flew to Ernest the moment he was at leisure and poured my grievances into his ear. “Well, dear,” he said, “suppose you give up the house-keeping to Martha! She will be far happier and you will be freed from much annoying, petty care.”

What.

Like seriously, what?!

Wouldn’t this essentially make Katy a guest in her own home, depriving her of the ability to make basic decisions about its running? While Katy does have ill health overall, she seems to be doing just fine. If Martha so desires to run something, perhaps she should go out and find employment. Or, given the period and her class status—which prevented many avenues of employment—perhaps a social cause?

A few generations later, Martha might have been a suffragette. Even here, in the 1830s, she could have become an abolitionist, or could have engaged in any manner of social reform efforts—even visiting the poor, as Katy’s mother does, would be an appropriate outlet.

But no. She wants to run Katy’s household.

Also, yes, Katy has a cook. She does not know how to bake bread. I’m genuinely curious what she spends her time doing. Does she have a maid who cleans, or does she do that bit? There was a lot of work that went into running a household at this time, but cooking—which surely also includes shopping—seems like a pretty big chunk of it.

Perhaps there is a lot of sewing and mending?

But anyway, Katy agrees reluctantly to give this a try—to let Martha run the household, and see if Sarah, the cook, will stay on after all.

I bit my tongue lest it should say something, and went back to Sarah.

“Suppose Miss Elliott takes charge of the housekeeping, and I have nothing to do with it, will you stay?”

“Indeed, and I won’t then. I can’t bear her, and I won’t put up with her nasty, scrimping, pinching ways!”

“Very well. Then you will have to go,” I said, with great dignity, though just ready to cry. Ernest, on being applied to for wages, undertook to argue the question himself.

“My sister will take the whole charge,” he began.

“And may and welcome for all me!” quoth Sarah. “I don’t like her and never shall.”

“Your liking or disliking her is of no consequence whatever,” said Ernest. “You may dislike her as much as you please. But you must not leave us.”

“Indeed, and I’m not going to stay and be put upon by her,” persisted Sarah. So she has gone.

So that’s … fun.

I wanted a cheerful home, where I should be the centre of every joy; a home like Aunty’s, without a cloud. But Ernest’s father sits, the personification of silent gloom, like a nightmare on my spirits; Martha holds me in disfavor and contempt; Ernest is absorbed in his profession, and I hardly see him. If he wants advice he asks it of Martha, while I sit, humbled, degraded and ashamed, wondering why he ever married me at all.

See, I didn’t have to deal with this in my early years of marriage. The closest thing I can think of is some conflict over how much time my husband spent playing video games. (And mostly, I just needed to get over that, and realize that video games, actually, could be pretty fun.) I cannot imagine having my father-in-law and adult sister-in-law move in with us within two months of getting married.

OCT. 2.-There has been another explosion. I held in as long as I could, and then flew into ten thousand pieces. Ernest had got into the habit of helping his father and sister at the table, and apparently forgetting me. It seems a little thing, but it chafed and fretted my already irritated soul till at last I was almost beside myself.

Yesterday they all three sat eating their breakfast and I, with empty plate, sat boiling over and, looking on, when Ernest brought things to a crisis by saying to Martha,

“If you can find time to-day I wish you would go out with me for half an hour or so. I want to consult you about-”

“Oh!” I said, rising, with my face all in a flame, do not trouble yourself to go out in order to escape me. I can leave the room and you can have your secrets to yourselves as you do your breakfast!”

I don’t know which struck me, most, Ernest’s appalled, grieved look or the glance exchanged between Martha and her father.

Ouch.

I sympathize with Katy’s apparent need to hold everything in and until it all spills out in the worst way, because, again, I often behaved similarly in the early years of my marriage. I still do, sometimes, but I’ve learned that these conversations are best had before they get to the point that I’m about to boil over.

Katy runs off to the bedroom, completely embarrassed. Ernest comes after her.

“What was it vexed you, dear? What is it you can’t stand? Tell me. I am your husband, I love you, I want to make you happy.”

So, I’ve had my issues with Ernest, and these issues haven’t necessarily disappeared, but seriously, in this moment, good on Ernest. I’m also beginning to wonder whether this book has appealed primarily to evangelical women who aren’t quite as fundamentalist as Debi Pearl. Can you imagine Michael Pearl saying something like that?

Katy responds as follows:

“Why, you are having so many secrets that you keep from me; and you treat me as if I were only a child, consulting Martha about everything. And of late you seem to have forgotten that I am at the table and never help me to anything!”

“Secrets!” he re-echoed. “What possible secrets can I have?”

Despite how aghast and defensive he sounds there, Ernest really is listening.

“Indeed, Ernest, I don’t want to be selfish or exacting, but I am very unhappy.”

“Yes, I see it, poor child. And if I have neglected you at the table I do not wonder you are out of patience. I know how it has happened. While you were pouring out the coffee I busied myself in caring for my father and Martha, and so forgot you. I do not give this as an excuse, but as a reason. I have really no excuse, and am ashamed of myself.”

“Don’t say that, darling,” I cried, “it is I who ought to be ashamed for making such an ado about a trifle.”

“It is not a trifle,” he said.

On the one hand, yes, Ernest just called Katy “poor child.” Yes, that’s really, really weird. On the other hand, when Katy did that thing where she immediately started doubting herself and her concerns, Ernest didn’t feed that doubt, he backed her up. It is not a trifle.

That’s powerful.

Of course, it turns out he absolutely did have secrets, as we shall see.

“I dare say I have been careless about consulting Martha. But she has always been a sort of oracle in our family, and we all look up to her, and she is so much older than you. Then as to the secrets. Martha comes to my office to help me look over my books. I have been careless about my accounts, and she has kindly undertaken to attend to them for me.”

“Could not I have done that?”

“No; why should your little head be troubled about money matters?”

So, yes, I can imagine Michael Pearl saying that.

“But to go on. I see that it was thoughtless in me not to tell you what we were about. But I am greatly perplexed and harassed in many ways. Perhaps you would feel better to know all about it. I have only kept it from you to spare you all the anxiety I could.”

“Oh, Ernest,” I said, “ought not a wife to share in all her husband’s cares?”

Team Katy!

“‘No,” he returned; “but I will tell you all that is annoying me now.”

Damnit, Ernest!

“My father was in business in our native town, and went on prosperously for many years. Then the tide turned – he met with loss after loss, till nothing remained but the old homestead, and on that there was a mortgage. We concealed the state of things from my mother; her health was delicate, and we never let her know a trouble we could spare her. Now she has gone, and we have found it necessary to sell our old home and to divide and scatter the family My father’s mental distress when he found others suffering from his own losses threw him into the state in which you see him now. I have therefore assumed his debts, and with God’s help hope in time to pay them to the uttermost farthing. It will be necessary for us to live economically until this is done. There are two pressing cases that I am trying to meet at once. This has given me a preoccupied air, I have no doubt, and made you suspect and misunderstand me. But now you know the whole, my darling.”

You see. He did have secrets. He has assumed his father’s debts and Martha is trying to help him fix it. Ninteenth century doctors didn’t actually make that much money, at least not ones like Ernest, who almost certainly doesn’t charge for the care he provides the poor.

“But I think, dear Ernest,” I added, “if you will not be hurt at my saying so, that you have led me to it by not letting me share at once in your cares. If you had at the outset just told me the whole story, you would have enlisted my sympathies in your father’s behalf, and in your own. I should have seen the reasonableness of your breaking up the old home and bringing him here, and it would have taken the edge of my bitter, bitter disappointment about my mother.”

Ah, see. That.

“I am truly sorry. And now my dear little wife must have patience with her stupid blundering old husband, and we’ll start together once more fair and square. Don’t wait, next time, till you are so full that you boil over; the moment I annoy you by my inconsiderate ways, come right and tell me.”

I don’t think that’s sarcasm.

What’s interesting is that the point here is not women shouldn’t question their husbands, their husbands always know best, it’s these two young people are still learning how to do married life, and are making a lot of mistakes along the way. Yes, Katy shouldn’t have waited until she boiled over to say something—but also Ernest should have told her what was going on to begin with.

“May I ask one thing more, now we are upon the subject?” I said at last. “Why couldn’t your sister Helen have come here instead of Martha?”

He smiled a little.

“In the first place, Helen would be perfectly crushed if she had the care of father in his present She is too young to have such responsibility. In the second place, my brother John, with whom she has gone to live, has a wife who would be quite crushed by my father and Martha. She is one of those little tender, soft souls one could crush with one’s fingers. Now, you are not of that sort; you have force of character enough to enable you to live with them, while maintaining your own dignity and remaining yourself in spite of circumstances.”

Ah, but apparently she doesn’t have force of character enough to be told about Ernest assuming his father’s apparently large debts.

Does Ernest see the double standard he’s using here?

Katy seems to completely miss the words of praise. Instead, she is merely surprised that Ernest has spoken critically of Martha. Did he not want her to be just like Martha? Ernest responds in the negative, and says he wants her to be herself. Thankfully, Katy brings up his earlier request that she not prattle on so in front of his father.

“Yes, dear; it was very stupid of me, but my father has a standard of excellence in his mind by which he tests every woman; this standard is my mother. She had none of your life and fun in her, and perhaps would not have appreciated your droll way of putting things any better than he and Martha do.”

I could not help sighing a little when I thought what sort of people were watching my every word.

“There is nothing amiss to my mind,” Ernest continued, “in your gay talk; but my father has his own views as to what constitutes a religious character and cannot understand that real earnestness and real, genuine mirthfulness are consistent with each other.”

And with that the conversation ends, but progress has been made.

I understand him now as I never have done, and feel that he has given me as real a proof of his affection by unlocking the door of his heart and letting me see its cares, as I give him in my wild pranks and caresses and foolish speeches.

It’s funny, when I returned to this book, having not read it since my teen years, I expected to hate it. And, in some parts, I certainly do.

I don’t particularly like—or understand—Katy in the book’s first section, and I rather despise her mother. Once Katy begins staying with her Aunty, though, things start to look up—and, while her courtship with Ernest was badly flawed and cringe inducing, Prentiss’ portrayal of Katy’s marriage, and of Katy’s coming into her own during it, feels more real than many contemporary novels I have read.

There are bits of Katy’s marriage that are a product of the sexist gender norms present in 19th century U.S.—such as Ernest’s reluctance to bother Katy with their finances—but even here, Prentiss puts these things in her story only to have Katy push back against them. It’s very clear that the marriage Katy envisions is functionally egalitarian, albeit with a division in household roles.

I begin to wonder whether the evangelical women I saw reading this book when I was a teen were moved by a conviction that they needed to live up to certain ideals, or by a wish that their marriages could be more like the one Katy forges her own space in over time.

Perhaps this book escaped the censors because its radical egalitarian elements are wrapped in 19th century domestic trappings.

I have a Patreon! Please support my writing!