Stepping Heavenward, Chapter X part 2 to Chapter XI part 1

In this section, Katy marries Ernest. His mother dies soon after, and his sister and father have to come live with him and Katy. This is particularly difficult for Katy because she had hoped her mother could come live with them. This section is interesting for several reasons, the first being its description of the tensions of extended families living together, something that happened often then but seldom now.

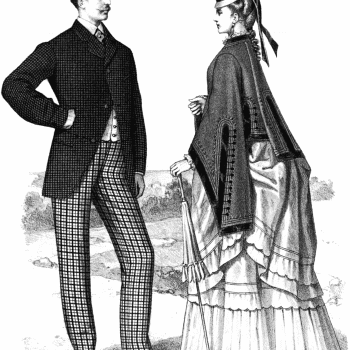

The more I’ve read of this book the more I’ve become convinced that it is popular among a subset of conservative evangelicals today not because it was at all conservative at the time it was written but rather because it was written at a time when gender norms were more “traditional.” Katy aspires to be a wife and mother. There is no thought of her having a job outside of the home. But then, there wouldn’t be, would there? This book was published in 1869, and is set (thus far) in the 1830s.

But the reality is more complicated. The characters of this book are ensconced in a narrow middle class where a woman taking in work would be unseemly. Importantly, Katy lives in a world where there are servants. Even in her newlywed state, with just herself and her husband in the household, they have a cook. Her name is Sarah. She works outside of the home, and Katy has no problem facilitating that.

Katy doesn’t aspire to be a wife and mother because she believes it is unbiblical for women to work outside of the home. She aspires to be a wife and mother because, at that time, in her society, that was what a woman aspired to.

In other words, there is nothing revolutionary about Katy’s aspiration. Conservative evangelicals in our modern world who argue that women—or, in particular, mothers—should not work outside of the home are being countercultural. Their belief is framed in large part as a rejection of the norms and mores of the world around them. That is not so here. Katy is no countercultural revolutionary homemaker.

Katy also is not at all wedded to the idea of wifely submission. There is nothing at all said about wives submitting to their husbands, and Katy does not do it. Indeed, Katy pushes back against Ernest, disagrees with him, and asserts herself. She believes she has every right to do so. Katy acts as though she is every bit Ernest’s equal, doing and saying things Debi Pearl and Lori Alexander would surely bee appalled at.

Why, then, is this book so popular amongst a swath of conservative evangelicals that overlaps with Debi and Lori’s readership? Why did my mother read the book repeatedly? Why is it being reprinted and sold to evangelical homeschool moms?

I think perhaps the reason is this—Katy lives a life that fits within the domestic ideals of motherhood and wifehood touted among this swatch of evangelicals—in large part because these were the norms at the time she was living—but as she does so, Katy never gives up her sense of who she is. She promises women like my mother a way to meet the ideals put upon them by their churches and religious teachers, without surrendering their senses of self—and even some sense of independence.

All this being said, let’s turn to the book.

Katy and Ernest have just confessed their love for each other, and Katy is deliriously happy.

APRIL 25. One does not feel like saying much about it, when one is as happy as I am. I walk the streets as one treading on air. I fly about the house as on wings. I kiss everybody I see.

Now that I look at Ernest (for he makes me call him so) with unprejudiced eyes, I wonder I ever thought him clumsy. And how ridiculous it was in me to confound his dignity and manliness with age!

I definitely think romance tropes from the time are playing a role here. In Little Women, Professor Bhaer is described as having large hands, and while Jo recognizes his kindness the moment she meets him, there are some definite parallels.

Katy is, well, Katy.

It is very odd, however, that such a cautious, well-balanced man should have fallen in love with me that day at Sunday-school. And still stranger that with my headlong, impulsive nature, I deliberately walked into love with him!

Ah, so, we’re going with the love at first sight trope. Got it.

We have a time jump here—Katy goes home over the summer, and she and Ernest—for that is what I suppose we must now call him—exchange letters.

Katy is still lovestruck. So is Ernest. He describes her as “the most beautiful, the noblest, the most loving of human beings.”

Has anyone ever said this many nice things to Katy? I don’t think so. Katy’s mother spend all her time talking Katy down for her faults. It’s really no wonder Katy is so besotted with Ernest—he actually sees value in her, and believes she is a good person. That’s huge. Of course that means the world to her.

It’s true, when he first confessed his love for her, Ernest told Katy he knew all her faults already, so that did come up—and it felt profoundly insulting. Because, well—it was. It was a horrible first admission of romantic love. But her whole life, people have been ragging on Katy’s faults, so it also wasn’t out of the ordinary for her self-perception. His belief that she has virtues, though? That’s something Katy hasn’t dared to believe, thanks to her super-loving mother and, well, everyone else in her life.

Every time Katy has even toyed with thinking she has virtues, up to this point, she has become immediately convinced that that’s pride talking. Coming from someone else, though—that praise of her virtues would naturally feel different. In the warmth of the blazing sun that is Ernest’s infatuation, Katy finally finds room to believe that maybe—just maybe—she actually does have good traits.

But Ernest, just so we’re clear, is still in the infatuation puppy love stage. All is not rainbows for Katy from here on out. Katy, too, is in this same stage.

To think that I am always to be with Ernest! To sit at the table with him every day, to pray with him, to go to church with him, to have him all mine! I am sure that there is not another man on earth whom I could love as I love him.

And so the time turns, with ample skips in time, to Katy’s wedding, the day after her 21st birthday in January (their profession of love was in April).

Here, we learn two things. First, Katy has never met Ernest’s family. Katy says she’s glad of it, because she didn’t want to be “examined and criticized.” The only explanation we get is that his mother is not well. Second, one month after her wedding date, Katie writes that “our honeymoon ends to-day.” What.

Honey. Moon. Honeymoon.

Apparently it once just meant the first month of marriage. That actually makes a lot of sense, and somehow I can’t believe I didn’t know it. Huh.

Anyway, it very quickly becomes obvious that Katie isn’t as satisfied with married life as she had thought she would be.

FEB. 15. Our honeymoon ends to-day. There hasn’t been quite as much honey in it as I expected. I supposed that Ernest would be at home every evening, at least, and that he would read aloud, and have me play and sing, and that we should have delightful times together. But now he has got me he seems satisfied, and goes about his business as if he had been married a hundred years. In the morning he goes off to see his list of patients; he is going in and out all day; after dinner we sit down to have a nice talk together; the door-bell invariably rings, and he is called away. Then in the evening he goes and sits in his office and studies; I don’t mean every minute, but he certainly spends hours there.

It might have been a good idea for them to have talked about their expectations for married life before they got married.

One day Katy gets a letter from her mother—a kind and loving letter—that makes her break down into tears and then, well—it all came out.

I said I was lonely, and hadn’t been used to spending my evenings all by myself.

“You must get some of your friends to come and see you, poor child,” he said.

Child? That’s fun!

“I don’t want friends,” I sobbed out. “I want you.”

“Yes, darling; why didn’t you tell me so sooner? Of course I will stay with you if you wish it.”

“If that is your only reason, I am sure I don’t want you,” I pouted.

He looked puzzled. “I really don’t know what to do,” he said, with a most comical look of perplexity. But he went to his office, and brought up a pile of fusty old books.

“Now, dear,” he said, “we understand each other I think. I can read here just as well as down stairs. Get your book and we shall be as cosy as possible.”

My heart felt sore and dissatisfied. Am I unreasonable and childish? What is married life? An occasional meeting, a kiss here and a caress there? or is it the sacred union of the twain who ‘walk together side by side, knowing each other’s joys and sorrows, and going Heavenward hand in hand?

Oh dear god. Talk it out.

The friend Katie still calls only “Mrs. Embury”—the young wife of Ernest’s doctor friend—came by for a visit the next day, but Katie didn’t feel she could talk about any of this with her.

She said she thought one of the first lessons a wife should learn is self-forgetfulness. I wondered if she had seen anything in me to call forth this remark. We meet pretty often; partly because our husbands are such good friends, partly because she is as fond of music as I am, and we like to sing and play together, and I never see her that she does not do or say something elevating; something that strengthens my own best purposes and desires. But she knows nothing of my conflict and dismay, and never will. Her gentle nature responds at once to holy influences. I feel truly grateful to her for loving me, for she really does love me, and yet she must see my faults.

I should like to know if there is any reason on earth why a woman should learn self-forgetfulness that does not apply to a man?

Okay, first of all, go Katy! Girl has a point.

Second, Mrs. Embury is very clearly still an acquaintance, not really a friend. Katy doesn’t feel like she can open up to her yet. And that’s too bad. Katy needs a friend, someone she can pour out all her frustrations to, and bounce ideas off of. Someone who can help give her a reality check.

By the way, doctors apparently worked differently back then:

A lady told me that through the long illness of a sweet young daughter of hers, he prayed with her every day, ministering so skillfully to her soul, that all fear of death was taken away, and she just longed to go, and did go at last, with perfect delight.

I’m pretty sure you’d be at risk of getting your license revoked if you did something like this today. This is almost half doctor, half pastor—or missionary, maybe. Which—I mean—this was the 19th century.

Anyway, I’m going to end it here. Next week we see the storm break. Ernest’s mother dies and his father and sister move in with them, and it goes … badly.

But again … Katy doesn’t behave, in next week’s section, the way Lori or Debi would advise behaving. She doesn’t roll over and accept Ernest’s plans like they come from God. She pushes back, and gives him what for when she feels like he’s messed up. And he listens. He’s no Michael Pearl.

We’ll talk about this more next week—but I’m fascinated by the idea that conservative evangelicals in my mother’s circles would latch onto a book that teaches the value of wifehood and motherhood only inasmuch as it is set in the 19th century, when that was simply what women of Katy’s class were.*

* For the most part. I’m not forgetting women who were reforms, like the Grimke sisters, or women who were de facto social workers, like Louisa May Alcott’s mothers. Katy and her mother both dabble in this latter—especially her mother. They do not, however, go in for being reformers. This is in part because Prentiss appears to have been one who didn’t go in for that herself. Even though she lived before and during the Civil War, I couldn’t find anything suggesting she opposed slavery in any active way. She also doesn’t malign anti-slavery activists. She appears to have just ignored the issue entirely.

I have a Patreon! Please support my writing!