Stepping Heavenward, Chapter II, part 1

I’ll try to make this section succinct, as I’d like to cover ground a bit more quickly. It is now summer—June and July.

Dr. Cabot, the pastor of the church Katy attends, preaches a sermon to the young. He addresses himself to three groups: those who knew they did not love God; those who knew they did love God; and those who were unsure. He then invites those who felt they fell in each category to come speak with him on certain nights the following week. Katy feels she is in the unsure category.

When Katy goes to see Dr. Cabot on the assigned day, he asks her if she loves her mother, and then asks her how she knows she loves her mother.

“I feel that I love her. I love to love her, I like to be with her. I like to hear people praise her. And I try–sometimes at least–to do things to please her. But I don’t try half as hard as I ought, and I do and say a great many things to displease her.”

Dr. Cabot walks her through each part of that, asking if she feels the same about God. He asks if she feels love for God, if she likes to spend time with God, in prayer, and whether she likes to hear God praised. She says “no” to each.

He goes on as follows:

“You know you love your mother because you try to do things to please her. That is to do what you know she wishes you to do? Very well. Have you never tried to do anything God wishes you to do?”

“Oh yes; often. But not so often as I ought.”

“Of course not. No one does that. But come now, why do you try to do what you think will please Him? Because it is easy? Because you like to do what He likes rather than what you like yourself? … I have come now to the point I was aiming at. You cannot prove to yourself that you love God by examining your feelings towards Him. They are indefinite and they fluctuate. But just as far as you obey Him, just so far, depend upon it, you love Him.”

Katy asks whether she might be striving to obey God out of fear—a good question, I might add. Dr. Cabot tells her that she might even so obey her mother from fear, “but only for a season.” Eventually, fear will wear off.

When I was a young teen, I was pretty sure I was saved, but sometimes I still wondered. And then, sometimes, I’d get all twisted up in my thoughts. It was uncomfortable. My mother used to tell me that all the worrying about whether I was saved proved that I was saved, because if I wasn’t, I wouldn’t care so much about whether I was saved. This feels helpful in a similar way—Dr. Cabot says, essentially, that if she is striving to obey God, that is evidence that she loves him.

Not for Katy, though. She leaves Dr. Cabot’s feeling “like one in a fog.”

I cannot see how it is possible to love God, and yet feel as stupid as I do when I think of Him. Still, I am determined to do one thing, and that is to pray, regularly instead of now and then, as I have got the habit of doing lately.

The reason this is a big deal is that, prior to this period, there was a great deal of emphasis on an emotional—and often painful—moment of conversion. Yet Dr. Cabot does not ask Katy whether she has had such a moment, and he does not feed her uncertainty about her salvation in an attempt to bring one on.

Dr. Cabot, remember, is one of Prentiss’ mouthpieces—Prentiss is putting her own spin on theology in his mouth, as well as in others’ mouths. As scholar Candy Gunther Brown writes in her book on 19th century evangelical literature:

Prentiss used the clerical figure, Dr. Cabot, as a mouthpiece to authorize theological opinions, but simultaneously she challenged clerical/lay and male/female hierarchies by placing doctrinal instruction into the mouths of Mrs. Cabot, Katy, her mother, and her lay husband, Ernest.

You get the idea. Unlike Debi Pearl, who writes specifically to women, urging them to close their mouths and obey their husbands, Prentiss is asserting herself theologically in an ongoing discussion, using the tools at her disposal to speak not only to women but to all readers. Prentiss did not teach at a seminary, but she was a theologian nonetheless—and in sections like this, she pushed back against her own Calvinist upbringing.

Amelia goes to these meetings too, and on their way home together, they make up without actually saying anything about what happened—if you recall, Katy told Amelia she could be friends with Jane Underhill, but when Amelia went to talk to her, Katy felt jealous and became upset.

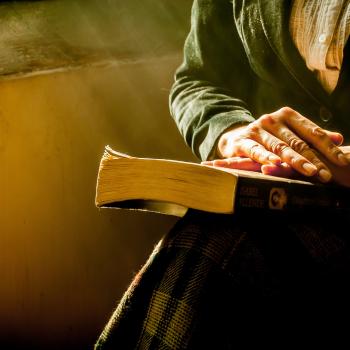

The school term gets out in late June, and Katy wins prizes for her drawing and her writing. Her mother orders four new dresses made for her, and the family makes plans for a trip—Prentiss does not stay where—and all of Katy’s resolutions to pray more regularly disappear. She refuses to see Dr. Cabot when he comes to visit her. She becomes fractious and miserable. This happens to Katy regularly; she can’t seem to find a sense of peace.

I’ll tell you what’s odd, though. This:

Amelia has been here. She has had her talk with Dr. Cabot and is perfectly happy. She says it is so easy to be a Christian! It may be easy for her; everything is. She never has any of my dreadful feelings, and does not understand them when I try to explain them to her. Well, if I am fated to be miserable, I must try to bear it.

Here’s the thing—I’ve read the whole book, and I know what happens to Amelia. Bad things. Bad things happen to Amelia. She runs after money, and parties, and beautiful dresses, and, well, that’s about it. She marries a shallow man set to inherit a great deal of money, she has three daughters, and then she catches, well, a disease. God knows what. Her husband loses interest in her now that she’s no longer gay and pretty, and she dies bereft and unsaved.

So here’s my question: what are we meant to take away from Amelia’s insistence that being a Christian is simple? What are we to gather from her confidence in salvation? Perhaps Prentiss hasn’t strayed as far from her Calvinist roots as she may think she has. Katy eventually gains an assurance in her salvation that runs in opposition to traditional Calvinism, true, but is this confidence something only to be gained after struggles and questions?

I’m honestly not sure.

Katy writes again in October, after school has started. Her brother James has gone away to college, and Katy misses him, despite how they were want to fight.

Several readers have stated in the comments section that they haven’t found all that much likable about Katy. Others have argued that she feels realistic to them. Either way, what seems to make Katy tick, more than anything else, is a desire to be liked and praised—something she doesn’t get as much from her mother as she likes. She does get it elsewhere, however.

Mrs. Gordon [Amelia’s mother] grows more and more fond of me, and has me there to dinner or to tea continually. She has a much higher opinion of me than mother has, and is always saying the sort of things that make you feel nice. She holds me up to Amelia as an example, begging her to imitate me in my fidelity about my lessons, and declaring there is nothing she so much desires as to have a daughter bright and original like me. Amelia only laughs, and goes and purrs in her mother’s ears when she hears such talk. It costs her nothing to be pleasant. She was born so.

For my part, I think myself lucky to have such a friend. She gets along with my odd, hateful ways better than any one else does. Mother, when I boast of this, says she has no penetration into character, and that she would be fond of almost any one fond of her; and that the fury with which I love her deserves some response.

I really don’t know what to make of mother. Most people are proud of their children when they see others admire them; but she does say such pokey things!

I don’t have a teenager yet, so I can’t say whether I would say such things about my children’s friends at that age. I certainly can’t imagine saying such a thing about one of my children’s friends now. The closest I’ve come is to affirm my older child’s observation that, yes, some kids are drama magnets in a way that others aren’t, and that, yes, that’s something she should be aware of.

I mean, really, Katy’s mother? Seriously?

I do love to get with a lot of nice girls, and carry on! I have got enough fun in me to keep a houseful merry. And mother needn’t say anything. I inherited it from her.

Evening.-I knew it was coming! Mother has been in to see what I was about, and to give me a bit of her mind. She says she loves to see me gay and cheerful, as is natural at my age, but that levity quite upsets and disorders the mind, indisposing it for serious thoughts.

This sounds like a period thing.

Katy disagrees with her mother’s assessment.

Other girls, who seem less trifling than I, are really more so. Their heads are full of dresses and parties and beaux, and all that sort of nonsense. I wonder if that ever worries their mothers, or whether mine is the only one who weeps in secret? Well, I shall be young but once, and while I am, do let me have a good time!

Oh lord. Katy wonders whether her mother is the only one who weeps in secret. What a lovely relationship they have. Simply splendid.

Katy wants to be liked, and she does not like to be judged. She feels her mother is constantly judging her, and that nothing she does is ever right. She doesn’t want to see Dr. Cabot, because she still can’t sort out why she would rather attend parties than pray, which she says makes her feel “stupid.” She would rather spend her time with Amelia and her mother, who say nice things about her, and make her feel liked, valued, and wanted.

And that is where I’ll leave Katy, for now.

I have a Patreon! Please support my writing!