The Stations of the Cross

A Devotional Guide for Lent and Holy Week

by Rev. Dr. Mark D. Roberts Copyright © 2011 by Mark D. Roberts and Patheos.com Note: You may download this resource at no cost, for personal use or for use in a Christian ministry, as long as you are not publishing it for sale. All I ask is that you acknowledge the source of this material: http://www.patheos.com/blogs/markdroberts/. For all other uses, please contact me at [email protected]. Thank you.

You may also be interested in:

The Seven Last Words of Christ: Reflections for Holy Week

Why Did Jesus Have to Die?

Daily inspiration for your life and work . . .

Life for Leaders is a daily, digital devotional that is sent out each morning from the Max De Pree Center for Leadership, where Mark works. This devotional, written by Mark and his team, will help you make connections between God, Scripture, and your daily work. You can check it out and/or subscribe here. There is no cost. Your email address will be used only for Life for Leaders. You can unsubscribe easily at any time.

The Stations of the Cross: Introduction

As near as I can remember, I first became aware of The Stations of the Cross while on vacation in San Francisco, California. As I visited St. Mary’s Cathedral, I noticed around the sanctuary of the church a series of visual reminders of Jesus’ last hours. These seemed to encourage the Catholic faithful in their personal devotion. I did not at the time realize the irony of my discovering The Stations of the Cross in San Francisco, a city named after St. Francis, the Catholic saint whose order had much to do with the development of devotion associated with The Stations of the Cross. Nor did I realize back then that virtually every Catholic church uses some form of The Stations of the Cross. I became more familiar with The Stations of the Cross, also known as The Way of the Cross, or Via Crucis (Latin, way of the cross) or Via Dolorosa (Latin, way of grief), when I began going on retreats that met at Catholic retreat centers. All of these places for prayer featured a series of scenes that depict the passion of Christ. Often, I saw people slowly walking along The Stations of the Cross, pausing at each station for quiet meditation and prayer.

A few years ago, I decided to follow The Way of the Cross at the Serra Retreat Center in Malibu, California (which, was situated, ironically, within a stone’s throw of the homes of Brittany Spears and Mel Gibson). Whereas almost all Catholic churches include the stations within the their place of worship (called the “nave,” Protestants would say the “sanctuary”), the Serra stations were outside in an aromatic grove of Eucalyptus trees. As I walked The Way of the Cross that day, I found myself reflecting with more intensity and emotion upon the events of Jesus’ death.

The exact origin of the devotional use of The Stations of the Cross is not entirely clear, though it is associated with Christian pilgrimages to Jerusalem in the early Christian centuries. (For a detailed online history, see “The Way of the Cross” in The Catholic Encyclopedia.) Those who were able to walk along the path Jesus walked on the way to his crucifixion were deeply moved by this experience. Yet, since the vast majority of Christians were not able to go to Jerusalem, The Way of the Cross enabled them to engage in a mini-pilgrimmage of sorts, whereby they could focus on the key events of Jesus’ last day. In the Middle Ages, this practice got wrapped up with the granting of indulgences (remissions of temporal punishments for sins for which we have been forgiven). The whole indulgence scene became quite messy and was in fact one of the major reasons for the Protestant Reformation. Thus, it’s not surprising that Protestants didn’t maintain the tradition of walking The Way of the Cross as an act of devotion. That practice seemed to include way too much theological baggage.

When I first followed The Stations of the Cross, I related readily to about half of the scenes. But the other half seemed odd to me because the statues depicted unfamiliar events, including: three falls of Jesus, an encounter between Jesus and his mother, and an encounter between Jesus and a woman named Veronica. These stations were not derived directly from Scripture, but rather from ancient church tradition. Though I wasn’t offended by the traditional nature of the unfamiliar scenes, since they were in no way contrary to Scripture, I found myself more drawn to the seven stations that were clearly based on the biblical record. I am, after all, a Protestant at heart, one for whom tradition can be helpful, but Scripture is the main source of my spiritual devotion.

Well, as it turns out, Pope John Paul II seems to have shared my concern about the lack of biblical foundation for the traditional Stations of the Cross, though he often celebrated these without hesitation. In 1991, John Paul II instituted a new series of fourteen Stations of Cross, each of which was based on Scripture alone. The chart below shows both the traditional and the revised stations (with Scripture references; these Scripture references come from the 2004 version of the Pope’s Stations of the Cross. The 1991 version had the same basic headings, but some different biblical texts.):

|

Traditional

|

Biblical

|

|

1. Jesus on the Mount of Olives (Luke 22:39-46)

|

|

|

2. Jesus, betrayed by Judas, is arrested (Luke 22:47-48)

|

|

|

3. Jesus is condemned by the Sanhedrin (Luke 22:66-71)

|

|

|

4. Peter denies Jesus (Luke 22:54-62)

|

|

|

1. Jesus is condemned to death

|

5. Jesus is judged by Pilate (Luke 23:13-25)

|

|

6. Jesus is scourged and crowned with thorns (Luke 22:63-65; John 19:2-3)

|

|

|

2. Jesus takes up his cross

|

7. Jesus takes up the cross (Mark 15:20)

|

|

3. Jesus falls for the first time

|

|

|

4. Jesus meets his mother

|

|

|

5. Jesus is helped by Simon the Cyrene to carry his cross

|

8. Simon of Cyrene helps Jesus to carry his cross (Luke 23:26)

|

|

6. Veronica wipes the face of Jesus

|

|

|

7. Jesus falls for the second time

|

|

|

8. Jesus meets the women of Jerusalem

|

9. Jesus meets the women of Jerusalem (Luke 23:27-31)

|

|

9. Jesus falls for the third time

|

|

|

10. Jesus is stripped of his garments

|

|

|

11. Jesus is nailed to the cross

|

10. Jesus is crucified (Luke 23:33, 47)

|

|

11. Jesus promises his Kingdom to the good thief (Luke 23:33-34, 39-43)

|

|

|

12. Jesus on the cross, his mother and his disciple (John 19:25-27)

|

|

|

12. Jesus dies on the cross

|

13. Jesus dies on the cross (Luke 23:44-46)

|

|

13. Jesus is taken down from the cross and given to his mother

|

|

|

14. Jesus is laid in the tomb

|

14. Jesus is placed in the tomb (Luke 23:50-54)

|

Several years ago, some folks at Irvine Presbyterian Church, where I served as pastor, decided to offer The Stations of the Cross as a devotional experience for Holy Week. We opted for the Pope’s biblically-based version of the Stations. My wife, Linda, offered to paint fourteen watercolor pictures that illustrated the passages upon which the revised stations are based. These were displayed in our church sanctuary during Holy Week. People were invited to come, to read Scripture, to reflect, and to pray. For many members of my church and community, this was a precious time of drawing near to the Lord in anticipation of Good Friday and Easter. (For the past several years, I have offered the use of Linda’s paintings for churches and Christian ministries without charge. Her paintings have appeared in literally thousands of places of worship on six continents. They are permanently installed in a number of churches. If you would like to use her paintings, all I ask is that you contact me and ask permission.)

For the next two weeks, I will offer a 15-part series of devotional reflections on The Stations of the Cross (including 14 stations plus an Easter postscript). I’ll “walk” through the stations with you, one station per day. At this pace we’ll complete the fourteen stations on Holy Saturday (which will feature the last of the stations). I’ll include the Scripture passages for each station, some personal reflections and prayers, and my wife’s paintings. My hope is that this online version of The Way of the Cross will enable you to enter into a deeper understanding and experience of the passion of Jesus, so that you might be ready to celebrate Easter with new joy and freedom.

P.S. from Mark You my be interested in a blog series I have written called: Why Did Jesus Have to Die? Roman, Jewish, and Christian Perspectives.

The First Station: Jesus on the Mount of Olives

Luke 22:39-46

He came out and went, as was his custom, to the Mount of Olives; and the disciples followed him. When he reached the place, he said to them, “Pray that you may not come into the time of trial.” Then he withdrew from them about a stone’s throw, knelt down, and prayed, “Father, if you are willing, remove this cup from me; yet, not my will but yours be done.” [Then an angel from heaven appeared to him and gave him strength. In his anguish he prayed more earnestly, and his sweat became like great drops of blood falling down on the ground.] When he got up from prayer, he came to the disciples and found them sleeping because of grief, and he said to them, “Why are you sleeping? Get up and pray that you may not come into the time of trial.”

Reflection

Growing up as a Christian, I always found the scene of Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane to be a comforting one. My feelings were shaped less by the actual story in the Gospels and more by a popular representation of the scene, first painted by Heinrich Hofmann and often reproduced by other artists and in other genres. As a boy, I once purchased a small wooden plaque with a reproduction of Hofmann’s original. I was reassured by the serenity and strength of Jesus in the Garden, whose halo reflected the light of God shining down upon Him. My plaque sat alongside my bed for many of my young years, encouraging me to pray and to trust God more. I still love that classic image by Hoffman, perhaps because it reminds me of my early devotion to Jesus. But, as I have studied the Gospel texts that describe Jesus in the Garden, I’ve come to believe that Hofmann’s image doesn’t capture the full reality of the scene. To be sure, in the end, Jesus accepted the Father’s will and faithfully chose the way of suffering. But his time of prayer was anything but serene. Matthew, Mark, and Luke emphasize the agony of Jesus in the Garden. The Gospel of Luke specifically mentions Jesus’ “anguish” or “agony” (using the Greek word agonia, which can also mean “struggle”). Moreover, Luke adds that Jesus was so intense in prayer that his sweat became like drops of blood. In the other Gospels, Jesus explains that he is “deeply grieved, even to death” (Mark 14:34; Matt 26:38). Those Gospels also show Jesus as praying more than once before he was ready to accept the Father’s will. He was indeed struggling in the Garden. (Verses 43-44 are in brackets in the NRSV to indicate that they don’t appear in all ancient manuscripts. Some scholars believe that the verses were excised by certain scribes because of their shocking portrayal of Jesus. The majority of scholars hold that these verses were added later, and came from some tradition about Jesus that was not in the first edition of Luke.)

Although I am still fond of Heinrich Hoffman’s painting of Jesus in the Garden, another image now captures my imagination as I reflect upon the Gospel accounts of Jesus’ agonizing prayer. This image comes, appropriately enough, from the actual Garden of Gethsemane. Last summer, I was able to visit this site in Jerusalem, including the Garden, which has been wonderfully preserved. (You can see some of my photos of the Garden here.) One of the walls of Gethsemane, which is part of the Church of All Nations, includes a small sculpture embedded in a wall. It could easily be missed. Yet, I’m so glad I didn’t overlook it, because it offers an image of Jesus that fits what we see in the biblical Gospels. Here we sense the agony of Jesus as he struggles with his Father’s will. A struggling Jesus? A Jesus who at first wants something other than his Father’s will? A Jesus who wishes to pass on the cup of suffering?

If you’re a Christian who believes that Jesus was not just a human being, but also the unique Son of God, the Word of God in flesh, then the scene in Gethsemane is shocking. It stretches our understanding and boggles our simplistic explanations of who Jesus really is. In Gethsemane, perhaps more than in any other scene of the Gospels, we see the fully human Jesus, the One who “in every respect has been tested as we are, yet without sin” (Hebrews 4:15). This means, among other things, that Jesus understands when we are tested, when we are weak, when we aren’t sure we want God’s will for our lives. In Jesus, we have, not a god who is watching us from a distance, but One who knows our every weakness, and who is there to help us in our time of trial. Indeed, Scripture teaches that Christ himself intercedes for us (Romans 8:34).

Whatever picture of Gethsemane you keep in your mind, may you let the text of Scripture fill out its meaning. May you be encouraged to come before God with complete honesty, holding nothing back. May you pour out your heart to the Lord. May you wrestle with God’s will for you. As you do, know that Jesus understands, and is there to help you.

Prayer

Lord Jesus, as I reflect upon your experience in Gethsemane, I am once again astounded by your utter humanness. You are not God-in-flesh-well-sort-of, but truly God in human flesh. You are Emmanuel, God with us. Thus you are also God with me. You understand me. You stand with me in hard times. You encourage me when I wrestle with the Father’s will. And you intercede for me. How I thank you, dear Lord, for who you are, for what you have done, and for what you are doing in my life today. Amen.

The Second Station: Jesus, Betrayed by Judas, Is Arrested

Luke 22:47-48

While he was still speaking, suddenly a crowd came, and the one called Judas, one of the twelve, was leading them. He approached Jesus to kiss him; but Jesus said to him, “Judas, is it with a kiss that you are betraying the Son of Man?”

Reflection

A few years ago, there was much abuzz about Judas as Holy Week approached. With great fanfare, the National Geographic Society had just released the text and translation of the Lost Gospel of Judas. This second-century writing focused on Judas and his special relationship with Jesus. Not only was Judas able to receive esoteric knowledge of Jesus, but also he was going to be one to “sacrifice the man that clothes [Jesus]” (56). What we consider an act of treachery was, according to the Gospel of Judas, that which proved Judas’ excellence. In typical Gnostic fashion, the human body is something to be escaped so that one, in this case, Jesus, could enter the world of pure spirit. Though a few scholars and lots of pseudo-scholars suggested that the Gospel of Judas revealed something of the true relationship between Jesus and Judas, the vast majority of scholars rejected this thesis. (You can find my evaluation here.)

The Gospel of Judas is a valuable source of information about second-century Gnostic belief, but has nothing to do with the actual lives of Jesus and Judas. What we read in the biblical Gospels is what really happened: Judas betrayed Jesus with a kiss. In the culture of the time, a kiss was a sign of love and loyalty. A disciple might indeed kiss his master to signify the specialness of their relationship. There was nothing sexual about the kiss. It was the sort of kiss that a son might give a father. I wonder why Judas chose to identify Jesus, indeed, to betray him, with a kiss. After all, he could have simply pointed to Jesus, or called out his name, or said to the soldiers: “He’s the one over there.” Yet Judas chose a kiss. Why? Of course we don’t know for sure and can only speculate. I wonder if Judas was saying to Jesus: “I’m doing this because I committed to the coming of the kingdom. I’m forcing your hand, Jesus, so that you’ll reveal your true messianic ministry and call up legions of angels to defeat the Romans.” Or perhaps Judas’ kiss meant: “I once believed in you, Jesus. I loved you. But you betrayed me. You held out the promise of the coming kingdom and I bought it completely. But then you started talking about your death, just like a defeated man. And everything started to unravel, including my hopes for you. So I still love you, Jesus, but I can no longer support you because you betrayed me and our cause.” From our perspective, it’s easy to condemn Judas. Few people in history have been more despised, and for good reason. Yet by heaping still more disdain on Judas, we miss the chance to confront the Judas in ourselves. What about our own mixed responses to Jesus?

How many times have we betrayed Jesus, not in the obvious and literal way of Judas, but in our hearts and actions?

How many times have we confessed Jesus as Lord, only to enthrone ourselves as the true lord of our lives?

How many times have we worshiped Jesus with our lips, not with a kiss, but with words, songs, and prayers, only to reject him in our hearts and actions?

When I stand back from myself and reflect, I want to be completely devoted to Jesus. But in the day-to-day challenges of faith, the Judas lurking within me sometimes reveals himself. I too can betray my Lord.

Prayer

O Lord, as much as I hate to admit it, to myself and to you, there is a bit of Judas in me. Forgive for the times I have pledge my love for you, only to reject you in the way I live. Help me to see where my commitment to you is mixed, where my heart is divided against itself. Set me free to be wholly devoted to you, even when I don’t understand you, even when I’m afraid that following you is too risky. Amen.

P.S. from Mark You my be interested in a blog series I have written called: Why Did Jesus Have to Die? Roman, Jewish, and Christian Perspectives.

The Third Station: Jesus is Condemned by the Sanhedrin

Luke 22:66-71

When day came, the assembly of the elders of the people, both chief priests and scribes, gathered together, and they brought him to their council. They said, “If you are the Messiah, tell us.” He replied, “If I tell you, you will not believe; and if I question you, you will not answer. But from now on the Son of Man will be seated at the right hand of the power of God.” All of them asked, “Are you, then, the Son of God?” He said to them, “You say that I am.” Then they said, “What further testimony do we need? We have heard it ourselves from his own lips!”

Reflection

According to Jewish law, it was wrong to try a criminal in the night. So, properly, those who accused Jesus waited until dawn, when the “assembly” or “council” could legally gather (the “council” is, more literally, the “Sanhedrin”). The leaders of the council, which was moderated by the high priest, wanted to know if Jesus claimed to be the Messiah. For them, this would be tantamount to a revolutionary claim, exactly the sort of thing that got the Jews into major trouble with Rome. False messiahs led to nothing but heartache and suffering for the Jewish people.

Given Jesus’s failure to raise up an army capable of setting Judea free from the Romans, there would have been little reason for the members of the Sanhedrin to believe that he was the true messiah. He didn’t fit the bill, as far as they were concerned. This may help to explain Jesus’ strange reticence with respect to his messiahship. Nowhere in the Gospels does he ever say, outright, “I am the Messiah.” Only in the Gospel of Mark does Jesus admit plainly to being the Messiah (Mark 14:62), but even there he quickly changes the subject to focus on the Son of Man seated at the right hand of God. Jesus knew that a claim to messiahship would have been misunderstood by his peers as a proclamation of revolution and the re-establishment of a Jewish kingdom. Of course Jesus didn’t deny that he was the Messiah either, something that might have allowed him to be released by the Sanhedrin with only a severe beating. His failure to say that he was not the Messiah, combined with his cryptic, “You say that I am,” was enough to convince the Sanhedrin of Jesus’ guilt.

And what was his crime? What had he done that was worthy of death? Well, for one thing, only days earlier Jesus had made a mess of the temple, interrupting its sacrifices and labeling it as a “den of robbers,” a phrase Jesus borrowed from Jeremiah in one of the ancient prophet’s predictions of the temple’s demise. By speaking so negatively of the temple, Jesus was seen by the Jewish officials to be speaking negatively of God himself. The temple was, after all, the house of God, the place where God had chosen to dwell. Thus, by speaking poorly of the temple, Jesus was believed to have been blaspheming God. Moreover, in his trial, Jesus not only wouldn’t reject his messiahship, but also he claimed that he would be “seated at the right hand of the power of God” as the promised Son of Man (Luke 22:69). This was perceived by the council, beginning with the high priest, as blasphemy and clear evidence of Jesus’ guilt. But making this claim wouldn’t have been a crime if Jesus was telling the truth. In the minds of the members of the Sanhedrin, however, there was no possibility of Jesus actually being the Son of Man who would share in God’s own power and glory. Sure, he could do a few miracles. But usher in the divine kingdom? Hardly. So the rabble-rouser, temple-destroyer, and all-around troublemaker was now, as far as the Sanhedrin was concerned, an obvious blasphemer. (Not all members of the Sanhedrin agreed that Jesus was guilty and worthy of death. Joseph of Arimathea, for example, “had not agreed to their plan and action” [Luke 23:51].).

Have you ever wondered why Jesus wasn’t clearer about who he was and what he had come to do? I certainly have. It seems like it would have been so much easier for all, including those of us who seek to follow Jesus today, if he had only said, “Yes, I am the Messiah, but not in the sense you expect. I have been anointed by God to bring the kingdom, but not in a military-political way. The kingdom is coming through transformed hearts, communities, and cultures. Most of all, the kingdom is coming through my death, as I bear the sin of Israel, and, indeed, the sin of the world. As Messiah, I must also suffer in the role of Isaiah’s Servant.” Yet Jesus didn’t say this. It’s something we have to piece together from his words and deeds. And we, like the people of his day, even his disciples, often get things confused. We rightly reject the notion of Jesus as a military-political Messiah. But then we tend to limit his saving work to post-mortem heaven for individual believers, rather than transformation of the whole cosmos, beginning with our world today. We don’t make the connection between Jesus as the Messiah and the prayer he taught us: “Thy kingdom come. Thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven.” When we confess Jesus as Christ or Messiah, we’re acknowledging him as our personal Savior. (“Christ” is an English variation of the Greek word christos, which is equivalent to the Hebrew mashiach, or “messiah.” They all mean “anointed one.”) But we’re saying more than this. We’re also recognizing that he came to inaugurate the kingdom of God. Though this kingdom won’t fully come until Jesus himself brings it, we get to share in the blessings and responsibilities of the kingdom even now. Our calling as followers of Jesus is to do the works of the kingdom, so that the reign of God might invade this world. At the same time, we look forward to the day when all will be fulfilled. Then, in the classic words of Revelation 11:15, put to such wonderful music in Handel’s Messiah, we’ll celebrate the fact that:

The kingdom of this world is become, The kingdom of our Lord, and of His Christ, And He shall reign forever and ever. Hallelujah!

Prayer

O Lord, the Jewish officials didn’t understand what it meant for you to be Messiah, and they condemned you as a criminal worthy of death. Your own followers didn’t understand what it meant for you to be Messiah, so they scattered and hid in your hour of crisis. Help me not to be like these! Help me to understand what it means when I confess you to be the Christ, the Messiah, the Anointed of God. And may this confession lead me to a life of true discipleship. Let your kingdom come, Lord, and your will be done, on earth as in heaven. And let this happen in my life, even today! Amen.

The Fourth Station: Peter Denies Jesus

Luke 22:54-62

Then they seized him and led him away, bringing him into the high priest’s house. But Peter was following at a distance. When they had kindled a fire in the middle of the courtyard and sat down together, Peter sat among them. Then a servant-girl, seeing him in the firelight, stared at him and said, “This man also was with him.” But he denied it, saying, “Woman, I do not know him.” A little later someone else, on seeing him, said, “You also are one of them.” But Peter said, “Man, I am not!” Then about an hour later still another kept insisting, “Surely this man also was with him; for he is a Galilean.” But Peter said, “Man, I do not know what you are talking about!” At that moment, while he was still speaking, the cock crowed. The Lord turned and looked at Peter. Then Peter remembered the word of the Lord, how he had said to him, “Before the cock crows today, you will deny me three times.” And he went out and wept bitterly.

Reflection

Why did Peter deny Jesus? He was one of the first to follow Jesus, leaving so much behind to walk the uncertain road of discipleship. He had seen mighty wonders as his Master healed the sick, cast out demons, and even raised the dead. Peter had witnessed the miracle of the transfiguration. And he had even walked on water for a few brief moments. So why did Peter, of all people, deny Jesus?

Because he was afraid. Fear. Fear can startle us in the middle of the night and keep us awake for hours. It prevents us from reaching for our dreams or from reaching out to others in love. Fear cripples our souls and binds our hearts. It locks us in prison and throws away the key. Fear. What power it can have over us! Fear leads us to do what we would otherwise never do, and it keeps us from doing that which we know to be right. When we’re afraid, we can forget our commitments, our values, our loves. In fearful moments, all we think of is how to protect ourselves, perhaps at any cost. In fear we can strike out thoughtlessly against a perceived enemy. In fear we run away rather than standing for what we believe. Fear causes our adrenaline to race and compromises our judgment. Peter was afraid, understandably so. All that he had hoped seemed to be crumbling before him. The one he believed to be the Messiah, the Savior of Israel, was now arrested. Jesus’ death seemed certain, and with his death the end of Peter’s reason for living. Moreover, seeing his powerful Master so helpless must have confused Peter. Why didn’t Jesus call down a legion of angels? Why did the one with the power to still the storm not use that power now? And if Jesus was helpless to defend himself, what did that mean for Peter? How could he escape a fate like that of Jesus . . . arrest, abuse, and finally execution? In confused fear, Peter did what only hours before he swore he would never do, denying his Master. The one who promised to go to prison and even to die with Jesus was now scurrying to protect himself. So he denied his Lord, not once, but three times, just as Jesus had promised. Fear had overtaken Peter’s consciousness and conscience.

I can understand what this might have been like for Peter, because I have experienced the blinding blast of fear. It happened about twelve years ago at Disneyland, of all places. I was at the Magic Kingdom with my wife and two small children. My son was about four at the time and my daughter only two. While we were finishing up lunch, Kara was playing in the area right around our table on an outdoor patio. All of sudden she was gone. My wife and I jumped up and looked all around. The patio was crowded with people, but not Kara. I told Linda to look nearby while I would fan out to see if she had wandered farther away. After about five minutes, we still couldn’t find her. At that point Nathan thought he would be helpful. “Kara went back to the river to see the ducks,” he suggested. I had just checked the lake, with no sign of Kara. Without knowing it, Nathan had expressed one of my fears precisely. Kara had gone to the lake to see the ducks and had wandered in over her head and drowned. This was not an impossible scenario. Linda and I told the Disneyland officials that Kara was lost and they sprang into immediate action. Soon, dozens of employees had joined us in the search for our daughter. I remember running, literally, in larger and larger circles away from our lunch spot, all along calling for Kara. I didn’t care what anyone thought of me. All that mattered was finding my daughter . . . alive. Terrible thoughts entered my head, pictures of drowning, kidnapping, and so forth. I tried to blot them out of my mind, but couldn’t keep them from spilling back in. Of course I was praying, consistently, with ever increasing desperation. In my panic, I found it hard to think straight or to pray reasonably. It was as if my logical faculties had been strangled by the crushing grip of fear. After about fifteen minutes, which felt like fifteen hours, I saw a Disneyland official carrying Kara back to our lunch spot. It turned out that a man near our table had been watching Kara play. He mistakenly thought she was part of another family. When that family left without her, he feared they had forgotten her. So he picked up Kara and went running off to find the other family. When he finally caught up with them, about ten minutes later, he was horrified to learn that she was not their child. So he immediately ran to bring Kara back, overflowing with apologies. Those moments holding Kara still are some of the most precious of my life. (At that point my adrenaline stopped pumping, and I was utterly exhausted. Kara, utterly unconcerned, just wanted to go on the Dumbo ride.)

If Peter felt anything like what I felt that fateful day, then I can understand why he denied Jesus. In saying this I’m not excusing his behavior. Not by a long shot. What Peter did was wrong. But I am saying that I can understand what he might have been feeling, and why he did something that he later found so horrifying and inexcusable. Fear has to power to make all of us do or say that which we later regret. Though you and I might never deny Jesus in such a blatant way as Peter did, I would suggest that we might indeed deny him is less obvious ways, also because of fear. Have you ever sensed that the Lord was urging you to do something for his sake, but then you chickened out because you were afraid? Have you known what it’s like to downplay the significance of your faith in some conversation because your were afraid of what people might think of you? Have you ever let fear keep you from experiencing the fullness of life in Christ? I know I have, too many times to count.

What is the antidote to such fear? It’s trusting God. It’s believing the Word of Christ. It’s experiencing the perfect love of God that casts out fear (1 John 4:18). We don’t conquer fear through rationalization and mind-control. Rather, we overcome fear by leaning more fully into the strong arms of God, and knowing that e will never let us go.

Prayer

Forgive me, dear Lord, when I let fear get in the way of my relationship with you. Forgive me for all the times I’ve fallen short in my discipleship because I’ve been afraid. Forgive me for failing to trust you when you’ve proven yourself to be so utterly worthy of trust. Help me, Lord, not to be like Peter in this story. When hard times come, help me to trust you more. When my adrenaline starts to pound, clouding my mind and suffocating my heart, help me to receive your peace. When I’m tempted to deny you, either in words or deeds, or by failing to speak or act, help me to trust and obey. May I live my whole life in honor of you! Amen.

The Fifth Station: Jesus is Judged by Pilate

Luke 23:13-25

Pilate then called together the chief priests, the leaders, and the people, and said to them, “You brought me this man as one who was perverting the people; and here I have examined him in your presence and have not found this man guilty of any of your charges against him. Neither has Herod, for he sent him back to us. Indeed, he has done nothing to deserve death. I will therefore have him flogged and release him.” Then they all shouted out together, “Away with this fellow! Release Barabbas for us!” (This was a man who had been put in prison for an insurrection that had taken place in the city, and for murder.) Pilate, wanting to release Jesus, addressed them again; but they kept shouting, “Crucify, crucify him!” A third time he said to them, “Why, what evil has he done? I have found in him no ground for the sentence of death; I will therefore have him flogged and then release him.” But they kept urgently demanding with loud shouts that he should be crucified; and their voices prevailed. So Pilate gave his verdict that their demand should be granted. He released the man they asked for, the one who had been put in prison for insurrection and murder, and he handed Jesus over as they wished.

Reflection

There has been a tendency in the Christian telling of the Passion story to exonerate Pilate, or at least to make him an unwilling pawn of the Jewish leaders and crowds. Pilate, it is claimed, was a truth-seeking man who was caught between a rock and a hard place. Were it not for the pressure he received from the Sanhedrin and their supporters, he wouldn’t have crucified Jesus. This view of the noble Pilate seems at first to fit the facts of the New Testament Gospels. But, upon closer scrutiny, it falls short in a number of crucial ways.

First, it overlooks Pilate’s record of cruelty in his dealings with the Jewish people. Far from being some benevolent ruler, Pilate frequently offended and grieviously mistreated those he was sent to govern. The Jewish historian Josephus records an instance when Pilate used money given to the Jerusalem temple for one of his pet projects. When a crowd of Jews objected, Pilate killed a great number of them (Antiquities 18.3.2). The Gospel of Luke records a similar instance when Pilate killed a number of Galilean Jews, mingling their blood with their temple sacrifices (Luke 13:1). The first-century Jewish philosopher, Philo of Alexandria, once wrote a letter to Caesar, in which, among other things, he blamed Pilate for: “briberies, insults, robberies, outrages, wanton injustices, constantly repeated executions without trial, and ceaseless and grievous cruelty.” (Legatio ad Gaium, 301-302).

Second, it’s unlikely that Pilate would have been forced to act contrary to his will by the Jewish leaders and the crowd they rounded up to call for the crucifixion of Jesus. Pilate was surely aware of Jesus’ widespread popularity among the Jewish people. This, in fact, would have been a major concern to him, especially during the Passover, when the normal population of Jerusalem (around 35,000) swelled to perhaps ten times that amount. In other words, if Pilate had wanted to keep Jesus alive, he surely could have “gone over the heads” of the Jewish leaders to the large group of Jesus’s supporters and admirers. Of course Pilate didn’t need anyone’s approval to have Jesus killed. He had the authority to order execution. But Pilate was no doubt concerned about whether such an action in the case of Jesus would lead to revolt. So, we have every reason to believe that Pilate in fact wanted Jesus to be crucified, otherwise he would not have sentenced Him to death.

Third, what we see in the Gospels is, in all likelihood, a carefully scripted plot by Pilate. Knowing how popular Jesus was among the masses, Pilate knew he faced the possibility of insurrection if he himself was believed to be responsible for the death of Jesus. So he had to find a way to use his authority to crucify Jesus, and, at the same time, to publicly wash his hands of this decision. Thus he cleverly toyed with the Jewish leaders and their supporters, until it appeared as if he was compelled against his will to have Jesus crucified. Thus Pilate could get rid of Jesus and, at the same time, insure that popular anger would be directed at Jewish leaders and not at himself and Rome. In another place I have written this about Pilate and his decision to have Jesus crucified:

The fact that Pilate had Jesus crucified strongly suggests that he saw Jesus as a threat to Roman order. Though not your ordinary brigand or revolutionary, Jesus proclaimed the kingdom of God (not Caesar) and accepted adulation as a messianic (kingly) figure. Moreover, even if his answers to Pilate were minimal, Jesus didn’t reject the charge that he claimed to be king of the Jews. So, even though Jesus wasn’t your run-of-the-mill Zealot, he was still the sort of person who was dangerous to Rome, and was therefore worthy of death, at least from the Roman point of view.

Why have I taken time to establish Pilate’s actual guilt for the death of Jesus? For one thing, this is an important antidote to the a-historical and anti-Semitic tendency among some Christians to exonerate Pilate and blame “the Jews” in general for the death of Jesus. To be sure, most (but not all) of the Jewish leaders in Jerusalem wanted Jesus killed, and plotted to that end. But Pilate must not be excused for his central role in the death of Jesus. He alone had the authority in Jerusalem to sentence Jesus to death by crucifixion, and he must bear this guilt. I have focused on Pilate for another reason as well. I see him as a paradigm of the person who fails to take responsibility for his actions. Perhaps Pilate really believed he was innocent of Jesus’ death. Perhaps, as I have suggested, he was playacting for his own political benefit. Either way, Pilate issued the verdict that sent Jesus to the cross. Yet he did so in such a way as to appear innocent of Jesus’ blood. He did not take responsibility for what he had done.

How often do we do this sort of thing ourselves? How often to we rationalize our sins, blaming them upon others?How often do we fail to take responsibility for what we have done wrong, preferring to assign credit to our parents for raising us wrong, our society for mistreating us, our boss for abusing us, our spouse for misunderstanding us? I can’t tell you how many times, as a pastor, I have heard people try to evade responsibility for their own sins by pointing to the sins of others. And, if truth be told, I’ve done plenty of this myself. Why is this wrong? Well, for one thing it’s dishonest. Yet, beyond this, when we fail to accept responsibility for our sins, then we lose the opportunity to experience forgiveness for them. If I’m blaming others when I do wrong, then surely I won’t confess what I’ve done as sin. And this, in turn, will keep me from experiencing the grace of God with respect to this particular sin. (I’m not saying this will keep me out of Heaven, but rather than I will fail to enjoy the fullness of God’s forgiveness in this life.) When we’re tempted to be like Pilate, we’d do well to remember a portion of the first letter of John in the New Testament:

If we say that we have no sin, we deceive ourselves, and the truth is not in us. If we confess our sins, he who is faithful and just will forgive us our sins and cleanse us from all unrighteousness. If we say that we have not sinned, we make him a liar, and his word is not in us. (1 John 1:8-10)

As you look at your life, don’t be like Pilate. Don’t try to wash your hands of that which you have done wrong. God isn’t fooled. Rather, tell God the truth about your sins so that you might experience His forgiveness through Christ.

Prayer

Dear Lord, You know how easy it is for me to be like Pilate. I don’t like to take responsibility for my failures. I find rationalization to be so natural. I can fool myself into thinking I haven’t really done wrong. So forgive me, Lord, when I follow the way of Pilate. Help me to acknowledge my sins, both to myself and to You, rather than wallowing in my pointless excuses and defenses. By Your Spirit, guide me to see clearly where I have missed Your mark, so that I might confess truly and fully. Help me to experience the forgiveness You offer in Christ, and to live in the freedom of the cleansing You alone provide. Amen.

The Sixth Station: Jesus is Scourged and Crowned with Thorns

Luke 22:63-65; John 19:2-3

Luke: Now the men who were holding Jesus began to mock him and beat him; they also blindfolded him and kept asking him, “Prophesy! Who is it that struck you?” They kept heaping many other insults on him.

John: And the soldiers wove a crown of thorns and put it on his head, and they dressed him in a purple robe. They kept coming up to him, saying, “Hail, King of the Jews!” and striking him on the face.

Reflection What cruel irony! Jesus finally received the words he deserved: “Hail, King of the Jews!” For once he wore a crown upon his head. Yet it was not the golden crown of sovereignty or the olive crown of victory, but the thorny crown of suffering. Scholars have shown that the thorns from which Jesus’ crown was composed were long and terribly sharp. No doubt they dug deep into the head of the suffering king. We can’t really imagine the physical pain, not to mention the emotional and spiritual anguish endured by the King of kings. What incomprehensible irony! Jesus, the true king of Israel, endured the pain and mockery of the crown of thorns as part of his humiliation for us and our salvation. What was the result of his torture, beyond the transient agony? Paul puts it this way in Philippians 2:5-11:

Let the same mind be in you that was in Christ Jesus, who, though he was in the form of God, did not regard equality with God as something to be exploited, but emptied himself, taking the form of a slave, being born in human likeness. And being found in human form, he humbled himself and became obedient to the point of death— even death on a cross. Therefore God also highly exalted him and gave him the name that is above every name, so that at the name of Jesus every knee should bend, in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue should confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father.

Did you catch that? Because Jesus humbled himself, because he endured the humiliation of the cross, including the crown of thorns, therefore God exalted him to the highest place. For Jesus, the path to glory as King of kings included the path of disgrace. Because he wore the crown of thorns, Jesus would receive the crown of universal worship.

One of my favorite hymns is “Crown Him with Many Crowns.” It is a celebration of the multi-faceted sovereignty of Christ. Curiously, however, even in its full, original nine verses, this fine hymn doesn’t mention Jesus’ crown of thorns, though it does refer to his death in several different ways, mentioning specifically his “pierced feet” and his wounded “hands and side.” I’d like to close today’s reflection by printing the most popular four verses of “Crown Him with Many Crowns.” I’ve added a new verse, which you’ll find in italics:

Crown Him with Many Crowns By: Matthew Bridges and Godfrey Thring

Crown him with many crowns, The Lamb upon his throne; Hark! how the heav’nly anthem drowns All music but its own: Awake, my soul, and sing Of him who died for thee, And hail him as thy matchless King Thro’ all eternity.

Crown Him the promised One, Messiah, Israel’s king, Who walked in servanthood along, The path of suffering. His honor struck in shame, His sacrifice adorns, His head bowed in humility, Enhanced with twisted thorns.

Crown him the Lord of life, Who triumphed o’er the grave, And rose victorious in the strife For those he came to save; His glories now we sing Who died, and rose on high, Who died eternal life to bring, And lives that death may die.

Crown him the Lord of peace, Whose pow’r a scepter sways From pole to pole, that wars may cease, And all be pray’r and praise: His reign shall know no end, And round his pierced feet Fair flow’rs of paradise extend Their fragrance ever sweet.

Crown him the Lord of love; Behold his hands and side, Those wounds, yet visible above, In beauty glorified: All hail, Redeemer, hail! For thou hast died for me: Thy praise and glory shall not fail Thro’out eternity.

Prayer

Gracious, merciful Lord, how hard it is to read of the abuse you suffered even prior to your crucifixion. I can’t even begin to imagine what you felt, not only physically, but especially in your soul. What can I say in response but “Thank you” for walking the path of suffering and shame for my sake. You took the abuse that I deserved, and gave me your glory in return. Help me, dear Lord, to honor you as my King in all that I do. May my words and deeds reflect your sovereignty and celebrate your glory. Amen.

The Seventh Station: Jesus Takes Up the Cross

Mark 15:20

After mocking him, they stripped him of the purple cloak and put his own clothes on him. Then they led him out to crucify him.

Reflection Jesus had said this would happen. For quite some time he had predicted his suffering and death. The first time came right after Peter confessed him to be the Messiah. Jesus responded: “The Son of Man must undergo great suffering, and be rejected by the elders, chief priests, and scribes, and be killed, and on the third day be raised” (Luke 9:22). So even though the Roman soldiers led Jesus out to crucify him, they were only doing what he had said they would do. Indeed, they were doing what he chose to happen and in many ways caused to happen. After all, Jesus had been preaching that God along was the true King, and that his kingdom was at hand . . . not exactly the kind of message Rome liked to hear. And Jesus had been in regular conflict with Jewish leaders, who saw him as a nuisance and a threat. Then, he stirred up the crowds by riding into Jerusalem as a messianic king. He disturbed the Jewish officials by ransacking the temple and halting its sacrifices, accusing the temple leaders of being no better than a bunch of thieves.

Jesus seemed even to know that Judas was planning to betray him, and to consent to the betrayal. Jesus did not defend himself before the Sanhedrin, perhaps because he knew this was a lost cause. But he didn’t try to set Pilate straight either. And, of course, Jesus did not call down legions of angels to deliver him. So, though “they led him out to crucify him,” Jesus was no passive victim. He picked up his cross and walked to Golgotha because he had chosen the way of suffering. He believed this to be the will of God, the way by which he would realize his messianic destiny. Jesus chose to suffer and die so that he might fulfill Isaiah’s vision of the Suffering Servant of God, the one who was “despised and rejected by others; a man of suffering and acquainted with infirmity.” As this Servant, Jesus “has borne our infirmities and carried our diseases.” Moreover, “he was wounded for our transgressions, crushed for our iniquities; upon him was the punishment that made us whole, and by his bruises we are healed” (Isaiah 53:3-5).

Prayer

Dear Lord, you chose the cross. Yes, the Jewish leaders accused you. And, yes, Pilate sentenced you. And, indeed, Roman soldiers led you to Golgotha. But in a very real sense they were simply working out what God had willed and you had freely and painfully chosen. How I thank you for this costly choice! Because you took up the cross, I can take up life in all of its fullness. Because you were led to die, I can be led into the eternal life. Because you bore my sin, I can enjoy your forgiveness. How good you are to me, dear Lord, my Savior! Amen.

P.S. from Mark You my be interested in a blog series I have written called: Why Did Jesus Have to Die? Roman, Jewish, and Christian Perspectives.

The Eighth Station: Simon of Cyrene Helps Jesus to Carry His Cross

Luke 23:26

As they led him away, they seized a man, Simon of Cyrene, who was coming from the country, and they laid the cross on him, and made him carry it behind Jesus.

Reflection

What a shock this must have been for Simon! After traveling almost a thousand miles from Cyrene in northern Africa to Jerusalem (Cyrene is in northern Africa, where Libya is today), he found the city jammed with pilgrims who, like Simon himself, had come to celebrate the Passover in Jerusalem. So Simon set up camp out in the countryside. On his way into the city, he stumbled into what might have looked from a distance like a parade. But then, as he drew near, Simon saw the horrific spectacle of a badly beaten man stumbling as he was forced to carry the beam of his cross on the way to being crucified. We don’t know whether Simon had any knowledge of Jesus prior to their encounter on the road to Golgotha. It’s likely that he knew nothing about the suffering man before that moment. As Simon watched in horror, all of a sudden he found himself pressed into action. The Roman soldiers, recognizing that Jesus didn’t have sufficient strength to carry his cross by himself, “seized” Simon and demanded that he carry the cross instead. No doubt Simon was hesitant, fearing that he might end up sharing Jesus’ fate. Yet he knew enough not to provoke the soldiers, so he took the cross as ordered. We don’t know much more about Simon than this, since he disappears from the biblical record at this point (See note below).

Although Simon only helped to carry the cross of Jesus and was not actually crucified, he nevertheless illustrates the theological truth found in the letters of Paul in the New Testament. In the letter to the Galatians we read:

I have been crucified with Christ; and it is no longer I who live, but it is Christ who lives in me. And the life I now live in the flesh I live by faith in the Son of God, who loved me and gave himself for me. (Galatians 2:19-20)

The letter to the Romans contains even more detail about what it means to be crucified with Christ:

What then are we to say? Should we continue in sin in order that grace may abound? By no means! How can we who died to sin go on living in it? Do you not know that all of us who have been baptized into Christ Jesus were baptized into his death? Therefore we have been buried with him by baptism into death, so that, just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, so we too might walk in newness of life. For if we have been united with him in a death like his, we will certainly be united with him in a resurrection like his. We know that our old self was crucified with him so that the body of sin might be destroyed, and we might no longer be enslaved to sin. For whoever has died is freed from sin. But if we have died with Christ, we believe that we will also live with him. We know that Christ, being raised from the dead, will never die again; death no longer has dominion over him. The death he died, he died to sin, once for all; but the life he lives, he lives to God. So you also must consider yourselves dead to sin and alive to God in Christ Jesus. (Romans 6:1-11)

When we put our faith in Christ, we shared in his death, not by literally dying, but by dying to sin. Our “old self” is crucified so that we might be set free from our bondage to sin. Thus, we are alive in Christ, who lives in us. Therefore, in a sense, we ought to identify with Simon of Cyrene, who found himself a surprised participant in the crucifixion of Christ. This is especially true since many of us became Christians without really knowing that we were dying to our old selves so that we might live anew in Christ. We were pitched a gospel of salvation and eternal life without the corollary call to servanthood, sacrifice, and death to sin and self. Thus, it was only later in our Christian pilgrimage when we discovered, like Simon, that we were expected to be “crucified with Christ.” Unlike Simon, however, we aren’t forced to pick up the cross of Christ. Jesus invites us to follow him, but even though he is our Lord, he doesn’t force us against our will to join him. Rather, he beckons to us, calling us to take up our cross and offering abundant life in return. As he once said to those who who interested in following him:

“If any want to become my followers, let them deny themselves and take up their cross daily and follow me. For those who want to save their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake will save it. (Luke 9:23-24)

If we take up the cross of Christ, we will lose our lives, only to discover that we have found true life in Him.

Prayer

Dear Lord, the powerful example of Simon reminds me that I am also to take up the cross and follow you. You have called me to die to myself so that I might live for you. I confess that sometimes I resist this call, even though I know that in dying to myself I find true life in you. So help me, Lord, to carry my cross, to give my life away so that I might receive the abundant life of your kingdom. I could not do this were it not for the fundamental fact that you took my place on the cross. Through you, I am forgiven and invited into the fullness of life. In your death, I am raised to new life. All thanks and praise be to you, Lord Jesus, for bearing my sin on the cross, so that I might bear the cross into eternal life, both now and forever. Amen.

Note:

Mark names Simon’s sons as Alexander and Rufus, presumably because these men were known to the community for whom Mark was writing (Rome? see Mark 15:21). Paul also mentions a Rufus in the close of his letter to the Romans (Romans 16:13). He might be the son of Simon, but this is only speculation. Some second-century Gnostics argued that it wasn’t Jesus who died on the cross, but Simon of Cyrene. There’s no basis for this in reliable historical texts. Some Muslims also hold this view, since they deny that Jesus died on the cross. Because of Simon’s north African origin, some have thought he might have been a black man. While this is possible, it is by no means certain. Yet it’s surely more likely that Simon was of darker complexion than he is sometimes pictured in traditional images.

The Ninth Station: Jesus Meets the Women of Jerusalem

Luke 23:27-31

A great number of the people followed him, and among them were women who were beating their breasts and wailing for him. But Jesus turned to them and said, “Daughters of Jerusalem, do not weep for me, but weep for yourselves and for your children. For the days are surely coming when they will say, ‘Blessed are the barren, and the wombs that never bore, and the breasts that never nursed.’ Then they will begin to say to the mountains, ‘Fall on us’; and to the hills, ‘Cover us.’ For if they do this when the wood is green, what will happen when it is dry?”

Reflection

Growing up, I pictured the last week of Jesus’ life in stark, simple terms. Jerusalem, in my imagination, no doubt colored by Sunday school film strips, was a small town of maybe a few hundreds residents. All of these people came out to hail Jesus as king on Palm Sunday. Then, all of these same people showed up at Pilate’s palace to call for his crucifixion. Though I wasn’t a hardcore anti-Semite, I believed that “the Jews” wanted Jesus dead because he claimed to be God. Whenever I pictured Jesus meeting the women of Jerusalem along the Via Dolorosa, there were just two or three women, no doubt followers of Jesus, who were weeping for him. Meanwhile, the rest of the Jewish crowd was egging on the Roman soldiers, eager to see Jesus crucified.

But a few years ago I began to study the New Testament records of Jesus’s death with greater care. To my surprise, I saw things I had completely overlooked before, things that changed my perception of Jesus’ last hours. For example, Luke 23:27 notes that “a great number of people followed [Jesus]” as he walked to Golgotha. Luke gives no indication that they were crying out for Jesus’ death. In fact, by mentioning the women weeping for Jesus, Luke implies that the “great number of the people” were upset by what was happening to him. There’s no evidence that that were egging on the Roman soldiers, as I once imagined. Luke makes this even clearer a few verses later, after Jesus’ death: “And when all the crowds who had gathered there for this spectacle saw what had taken place, they returned home, beating their breasts” (Luke 23:48). This can only mean that the great majority of Jews who witnessed Jesus’ crucifixion were horrified, not happy, to see him die. They were certainly not among those who had earlier called for his crucifixion in Pilate’s courtyard.

The fact that only a small minority of Jews in Jerusalem actually wanted Jesus to be killed is confirmed by another passage in the Gospels that I had once overlooked. In Matthew, as Jesus is teaching in the temple during the days before his death, we read:

When the chief priests and the Pharisees heard his parables, they realized that he was speaking about them. They wanted to arrest him, but they feared the crowds, because they regarded him as a prophet. (Matthew 21:45-46)

The Jewish leaders wanted to arrest Jesus, but “they feared the crowds.” Why? Because the crowds “regarded him as a prophet” and, by implication, would have been horrified to see him arrested and crucified.

My close reading of the Gospels, combined with study of first-century Jewish history and culture, has corrected my youthful misunderstandings. I now recognize that Jerusalem wasn’t a small village, but a substantial city of perhaps 30,000 or people residents. During the Jewish holidays, such as Passover, the population would swell to as much as ten times this amount. This means that a tiny percentage of the Jews in Jerusalem were directly involved with or actually called for the crucifixion of Jesus. His death was surely engineered by the Jewish leaders in collusion with Pilate and his Roman cohort. As far as we know, the vast majority of Jews in Jerusalem were either horrified by or unaware of what was going on with Jesus.

I think it’s important for us to understand what really happened in the death of Jesus for a number of reasons, not the least of which is the sad history of anti-Semitism among Christians. For too long it was acceptable to utter the familiar refrain, “The Jews killed Christ.” And for too long many Christians used this as an excuse to persecute Jews who lived centuries after the death of Jesus, and who therefore had nothing to do with his death. In fact, some Jews were involved in the death of Jesus, mostly the leaders of Jerusalem. But Pontius Pilate alone had the authority to crucify Jesus. According to the Gospels, the majority of Jews who had any awareness of Jesus’ death were grieved, not glad. If we blame “the Jews” for the death of Christ, we’re making a mistake.

And, of course, we’re also missing the main point. Jesus did not die primarily as a helpless victim of Roman or Jewish injustice. He chose to die on the cross in faithfulness to the Father’s will and so as to bear the sin of the world. If anyone is to blame for the death of Jesus, we are, because we have sinned. Thus in looking upon Jesus’ death, we join the women of Jerusalem in weeping, not only for Jesus, but also for ourselves. In the death of Jesus we see what we deserve, and we rightly feel appalled. Then the mystery of grace astounds us. We realize that Jesus is bearing our sin so that we might be forgiven, that he is dying in our place so that we might live in his place. We sense the wonder expressed in 2 Corinthians 5:21: “For our sake [God] made [Christ] to be sin who knew no sin, so that in him we might because the righteousness of God.” How amazing!

Prayer

Gracious God, to whatever extent there are remnants of anti-Semitism in me, please forgive me and cleanse my mind and heart. Help me not to blame others for the death of Jesus, but to see my own sin as sending him to the cross. Even more, help me to grasp the mystery of your grace, to see in the death of Jesus that which gives me life. May my weeping over the suffering of Jesus, and my sorrow over my own sin, turn to joy when I recognize the majesty of your mercy. Amen.

The Tenth Station: Jesus is Crucified

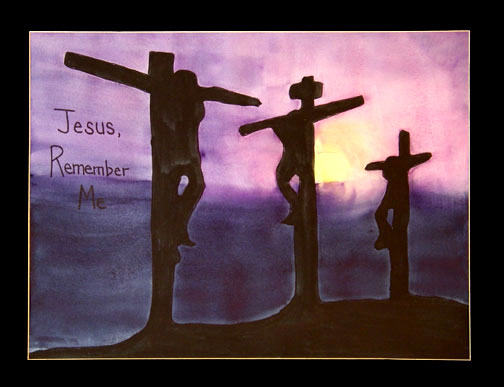

Copyright © 2007, Linda E. S. Roberts. For permission to use this picture, please contact Mark.

Luke 23:33-4, 47

When they came to the place that is called The Skull, they crucified Jesus there with the criminals, one on his right and one on his left. Then Jesus said, “Father, forgive them; for they do not know what they are doing.” And they cast lots to divide his clothing. When the centurion saw what had taken place, he praised God and said, “Certainly this man was innocent.”

Reflection

According to Luke, Jesus was crucified at “the place that is called The Skull” (23:33). The other Gospels mention that it was called Golgotha, the Greek transliteration of the Aramaic word Gûlgaltâ that means “skull.” We get the English word “Calvary” by way of the Latin calvariae locum, which means, “place of the skull.” The precise location of Golgotha is not clear from Scripture. It was near Jerusalem according to John 19:20, and therefore, by implication, not in the ancient city proper. Hebrews 13:12 mentions that Jesus “suffered outside the city gate.” John 19:41 adds that there was a garden in the place where Jesus was crucified. From the earliest days Christian tradition has identified the location of Golgotha in a place that is now within an ancient church in Jerusalem (the Anastasis Chuch, or Church of the Resurrection, also called the Basilica of the Holy Sepulchre). This church is now located near the center of Jerusalem. But in the first century this location was actually outside of the walls of the city.

Modern archeology has substantially confirmed the accuracy of traditional Christian belief about the location of Golgotha (Note). Since the nineteenth century, an alternative location for Jesus’ crucifixion has been popular. The so-called Gordon’s Calvary (near the Garden Tomb) does look somewhat like a skull, but most scholars don’t believe it was the location of Jesus’ death for a variety of reasons.

Christians throughout the ages have made pilgrimages to Golgotha, walking along the Via Dolorosa, and pausing to remember the Stations of the Cross along the way. A few years ago, I had the opportunity to visit Jerusalem and to make my way from the Mount of Olives, along the Via Dolorosa, to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Why? Why did I join the millions of Christians who have made a pilgrimage to Golgotha? There’s something about being in the actual place where something momentous happened that makes the event more real.

When I was in college, I used to ride my bike to Concord, Massachusetts, to the North Bridge, the place where “the shot heard round the world” began the War for Independence in 1775. As I leaned on that bridge and looked upon the peaceful countryside, I’d think about the men who died that day, and about the freedom I enjoy because of their sacrifice. I’d leave Concord with deeper gratitude for blessings I usually take for granted.

Sadly, I also can take the freedom I have in Christ for granted. For over four decades, I’ve known that Jesus died for my sins. And, even though I’ve staked my life upon this good news, there are times when it can almost seem old hat. A visit to Golgotha, like to the Concord bridge, retools my perspective. It reminds me that the death of Jesus really happened, in a real place at a real time. There the Lord of Glory suffered and died for the sins of the world . . . and for my own sins. Even if you are not able to visit Jerusalem, the Stations of the Cross allow you to approximate a pilgrimage to Calvary. The images and verses of the Via Crucis invite you to follow Jesus to the cross, so that you might experience deeper gratitude for the blessings of God’s amazing grace.

Prayer

Gracious Lord, how can I ever thank you for dying on the cross for me? Your death has given me life. Your sacrifice has led to my blessing. Yet I confess that I can sometimes take your death for granted, forgetting what you did for me and neglecting its significance. Forgive me, Lord. And even when I can’t go to the actual place of your crucifixion today, may the reality of your sacrifice press itself upon my mind and flood my heart. All praise to you, merciful Lord, for Your cross! Amen.

Notes

I have found three fairly helpful online discussions of the location of Golgotha: “Mt. Calvary” in The Catholic Encyclopedia, “Calvary” of Wikipedia, and “Where Was Golgotha?” from the Worldwide Church of God website.

P.S. from Mark You my be interested in a blog series I have written called: Why Did Jesus Have to Die? Roman, Jewish, and Christian Perspectives.

The Eleventh Station: Jesus Promises His Kingdom to the Good Thief

Luke 23:39-43

One of the criminals who were hanged there kept deriding him and saying, “Are you not the Messiah? Save yourself and us!” But the other rebuked him, saying, “Do you not fear God, since you are under the same sentence of condemnation? And we indeed have been condemned justly, for we are getting what we deserve for our deeds, but this man has done nothing wrong.” Then he said, “Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom.” He replied, “Truly I tell you, today you will be with me in Paradise.”

Reflection

Three men being crucified, suffering excruciating pain, literally. (The word “excruciating” comes from the Latin cruciare, “to crucify.”) One man begins taunting Jesus, sarcastically calling out for salvation he knows Jesus can’t deliver. The other, sensing something that he has never felt before, defends Jesus as an innocent victim. Then, in desperate hope, he cries out: “Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom.” In response Jesus says a most astounding thing, a most encouraging thing, a most curious thing: “Truly I tell you, today you will be with me in Paradise.”

It’s easy to imagine the jeers of the crowds at this point as they made fun of Jesus’ silly wishful thinking. After all, he’d only been on the cross for an hour or two. Most crucifixions lasted several days before the victim finally died from exhaustion, exposure, loss of blood, and suffocation. The crowds must have thought: “Today in Paradise? What a joke! All Jesus and the stooge beside him will experience today is ultimate pain and ultimate disgrace. If they are lucky, perhaps tomorrow they might die. And even then, Paradise? Hardly!”

The word “Paradise” comes from a Persian word meaning “garden.” It was used to describe a place of beauty, peace, and joy. In Jewish thought, Paradise represented the Garden of Eden and could stand for the joys of heaven. Paradise was just about as far as one could get from crucifixion. Yet, in spite of the apparent absurdity of it, and in spite of the spiteful laughter of the crowd, Jesus promises that the thief will join him in Paradise even this very day.

Luke 23:39-43 has often perplexed Christians who believe that salvation comes only by explicitly confessing Jesus as Savior and Lord. “Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom” hardly fits the bill here. Whatever the desperate thief believed about Jesus, it’s unlikely that he prayed what we call “the sinner’s prayer” while on his cross. Moreover, we have no reason to believe that Jesus straightened out the thief’s theology before offering the promise of Paradise. No, what we have in the text of Luke is a cry of minimal faith and maximal desperation. And what we have from the mouth of Jesus is a response of monumental mercy. It would be unwise to build a whole theology of salvation on the basis of this single passage from Luke.

It would also be unwise to build a theology of salvation without taking seriously this passage. Whatever else, it reminds us that God is “rich in mercy” (Ephesians 2:4). God saves us, not because we earn it, not because we deserve it, not because we say the right words and pray the right pryers, and not even because we get our theology right, but because God is full of mercy, mercy revealed and poured out through Jesus Christ, mercy that says to a thief: “Today you will be with me in Paradise.” If this crucified criminal could have hope, then perhaps you and I can as well. We hope, not in our goodness, not in our good intentions, but in the matchless mercy of God. As I reflect on Jesus’ response to the thief, I’m reminded of a marvelous hymn by Frederick William Faber, “There’s a Wideness in God’s Mercy.” It turns out that this hymn is actually an excerpt from a longer piece written by Faber, called “Souls of Men! Why Will Ye Scatter.” I’ll close today with all of Faber’s verses:

Souls of men, why will ye scatter like a crowd of frightened sheep?

Foolish hearts, why will ye wander from a love so true and deep?

Was there ever kindest shepherd half so gentle, half so sweet,

as the Savior who would have us come and gather round his feet?

There’s a wideness in God’s mercy, like the wideness of the sea;

there’s a kindness in his justice, which is more than liberty.

There is no place where earth’s sorrows are more felt than up in heaven;

there is no place where earth’s failings have such kindly judgment given.

There is welcome for the sinner, and more graces for the good;

there is mercy with the Savior; there is healing in his blood.

There is plentiful redemption in the blood that has been shed;

there is joy for all the members in the sorrows of the Head.

For the love of God is broader than the measure of man’s mind.

and the heart of the Eternal is most wonderfully kind.

But we make his love too narrow by false limits of our own;

and we magnify its strictness with a zeal he will not own.

Pining souls, come nearer Jesus, and O come not doubting thus,

but with faith that trusts more bravely his great tenderness for us.

If our love were but more simple, we should take him at his word:

and our lives would be all sunshine in the sweetness of our Lord.

Prayer

Dear Lord, how I thank and praise you for your mercy. You give us, not what we deserve, but infinitely better. Thank you for hearing my cries to you, and for responding to me much as you did to the thief who sought your help. Thank you for remembering even me, and for the promise I have of Paradise beyond this life. There’s much I don’t understand about the afterlife, but what I know is that I will be with you, seeing you face to face. And in your presence there will be fullness of joy. That’s more than enough for me! Amen.

The Twelfth Station: Jesus on the Cross, His Mother, and His Disciple

John 19:25-27

Meanwhile, standing near the cross of Jesus were his mother, and his mother’s sister, Mary the wife of Clopas, and Mary Magdalene. When Jesus saw his mother and the disciple whom he loved standing beside her, he said to his mother, “Woman, here is your son.” Then he said to the disciple, “Here is your mother.” And from that hour the disciple took her into his own home.

Reflection

Though most of the men who followed Jesus deserted him at the cross, his female followers remained to observe his death. All four New Testament Gospels mention this striking fact (Matt 27:55-56; Mark 15:40-41; Luke 23:49; John 19:25). John alone specifies that Mary the mother of Jesus was among the women who remained near him until the end. In the Gospel of John, Mary was standing next to “the disciple whom [Jesus] loved,” believed traditionally to be John, one of Jesus’ closest disciples and the source of the Gospel that bears his name. Observing these two, Jesus said to his mother, “Woman, here is your son,” and to the beloved disciple, “Here is your mother” (19:26-27). The writer of the Gospel adds, “And from that hour the disciple took her into his own home” (19:27).

The basic meaning of Jesus’ statement is clear. He was entrusting care of his mother to one of his most intimate friends and followers. He was making sure that she would be loved and cared for after Jesus’ death. Jesus knew he could trust his beloved follower with such an important responsibility. (We don’t know much about the relationship of Jesus and his natural siblings at this point. Earlier in his ministry they seemed to have been less than fully supportive of his ministry [see Mark 3:21]. Later, Jesus’ brother James became one of the main leaders of the Christian church.)

Commentators throughout the ages have rightly noticed Jesus’ attention to the needs of others, in this case his mother, even in his hour of excruciating suffering. This is a fine observation and surely fits with everything else we know about Jesus. But, for many years, I have been struck by the thought of what Jesus’ mother must have experienced as she watched her son being crucified. I can only begin to imagine her pain. When my father was dying slowly from cancer, his mother (my grandmother) was still alive. Her anguish over her son was palpable. At one point she said to me, “I’d give anything to change places with Dave. No mother should ever have to see her son suffer like this.”

I expect Mary could have said similar words as she stood near the cross of Jesus. Yet Mary might have understood that the death of her son was part of God’s mysterious plan. The Gospels don’t tell us too much about her experience or faith at this time. She surely knew from the very beginning that Jesus was extraordinary and that God had something very special in store for him. There were moments when she probably understood that Jesus’ destiny would not be an easy one, for him or for her. For example, in Luke 2, when Simeon praised God upon seeing the baby Jesus, he delivered a chilling prophecy to Mary, “This child is destined for the falling and rising of many in Israel . . . and a sword will pierce your own soul too” (2:34-35). As we reflect upon the meaning of Christ’s death this week, Mary’s presence at the cross reminds us of the deeply human drama that is occurring, even as this drama points beyond to the majesty and mystery of God’s plan for salvation.

Prayer

When I think of your mother, Lord, I remember that you weren’t just the Son of God bearing the sins of the world. You were also the son of Mary, the boy whom she loved. Mary gives us a touching reminder of your humanity, Lord. Because you were truly human, because you truly suffered, you did indeed bear the sins of the world, and mine as will. All praise be to you, Lord Jesus! Amen.

The Thirteenth Station: Jesus Dies on the Cross

Luke 23:44-47

It was now about noon, and darkness came over the whole land until three in the afternoon, while the sun’s light failed; and the curtain of the temple was torn in two. Then Jesus, crying with a loud voice, said, “Father, into your hands I commend my spirit.” Having said this, he breathed his last. When the centurion saw what had taken place, he praised God and said, “Certainly this man was innocent.”

Reflection

At first glance, Luke’s version of the centurion’s response to Jesus’ death seems like a glaring understatement. “Certainly this man was innocent,” rightly identifies Jesus’ lack of guilt. It makes clear once again the fact that he didn’t deserve to be crucified for sedition against Rome. He was no ordinary revolutionary, no guerrilla warrior, no terrorist. So, yes, “this man was innocent.” But couldn’t Luke have done better than this in his telling of the story? Mark’s version seems so much stronger: “Truly this man was God’s Son!”

We can’t be sure why Luke fashioned the narrative of Jesus’ death as he did. But we can understand that “Certainly this man was innocent” carried more weight with Luke than it might seem. Some translations, including the classic King James, have, “Certainly this was a righteous man” (23:47). This is a literal translation of the Greek, which uses the word dikaios to describe Jesus. Dikaios can mean innocent, but it is the usual word for “righteous,” and the base of such words as “righteousness, justice, justification” (dikaiosyne) and “justify” (dikaioo). From the lips of the centurion comes something far more than a recognition of Jesus’ innocence. It’s an ironic confession of his character as the righteous one, indeed, The Righteous One of God.

The fact that Jesus was The Righteous One identifies him with the Suffering Servant from Isaiah 53. In this classic passage we read:

He was despised and rejected by others; a man of suffering and acquainted with infirmity; and as one from whom others hide their faces he was despised, and we held him of no account. Surely he has borne our infirmities and carried our diseases; yet we accounted him stricken, struck down by God, and afflicted. But he was wounded for our transgressions, crushed for our iniquities; upon him was the punishment that made us whole, and by his bruises we are healed. All we like sheep have gone astray; we have all turned to our own way, and the LORD has laid on him the iniquity of us all. . . . Out of his anguish he shall see light; he shall find satisfaction through his knowledge. The righteous one [ho dikaios], my servant, shall make many righteous, and he shall bear their iniquities. Therefore I will allot him a portion with the great, and he shall divide the spoil with the strong; because he poured out himself to death, and was numbered with the transgressors; yet he bore the sin of many, and made intercession for the transgressors. (Isaiah 53:4-6, 11-12)

Because Jesus was righteous, because he was innocent, not just of crimes that deserved crucifixion, but of all wrongdoing, he was able to make many righteous by bearing the sin of others. He became the spotless sacrifice for all people. Thus, his being The Righteous One is absolutely essential for his death on the cross to bring about our salvation.