Thin Places:

A Biblical Investigation

What are thin places?

How should we think about them in light of Scripture?

by Rev. Dr. Mark D. Roberts

Copyright © 2012 by Mark D. Roberts and Patheos.com

Note: You may download this resource at no cost, for personal use or for use in a Christian ministry, as long as you are not publishing it for sale. All I ask is that you give credit where credit is due. For all other uses, please contact me at [email protected]. Thank you.

Thin Places: An Introduction

I first heard someone use the phrase “thin place” about twenty years ago. She had become a devotee of Celtic spirituality, from which source she had discovered the label “thin place.” She was terribly enthusiastic about the idea of “thin places” and proceeded to use this phrase to excess, which didn’t add to my enthusiasm for the phrase. Nevertheless, she got me thinking about thin places for the first time.

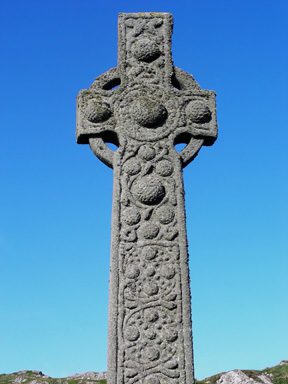

Celtic spirituality, by the way, has nothing to do with Boston’s basketball team. The word “Celtic” (pronounced KEL-tik, in this case) refers to a variety of Christian devotion practiced in Ireland and Scotland since the fifth century A.D. In recent years, there has been a revival of interest in Celtic spirituality, partly because of the popularity of Celtic religious art, and partly because of the wide influence of the Iona Community, a Christian community on the Scottish island of, you guessed it, Iona.

The woman who introduced me to the phrase “thin place” explained its meaning in this way. “A thin place,” she said, “is a place where the boundary between heaven and earth is especially thin. It’s a place where we can sense the divine more readily.” I wondered why this person, a respected Christian leader, seemed to have a hard time speaking of relationship with God. “Thin place” seemed almost to function as a circumlocution, a way getting around actually saying “God is especially present here” or “I can sense God’s presence here.” I also wondered about the whole idea of thin places. Are there such places? If so, why are they thin? Something about the whole notion of thin places made me nervous, theologically speaking, but I couldn’t quite put my finger on the problem.

Since my first exposure to the phrase “thin place,” I’ve probably heard it used five hundred times, maybe more. In certain Christian circles, Celtic Christianity has become wildly popular and so has the use of “thin place” to describe places where people experience God (or “the divine,” if you prefer something less personal). I have tended to resist this language, partly because of its trendy overuse and partly because of my nagging discomfort about its meaning.

Well, in the irony of God’s sovereignty, I’ve ended up working in a place that people love to identify as thin. For the past four and a half years, I have been working with Laity Lodge, a retreat center in the Hill Country of Texas. I’ve heard Laity Lodge described as a thin place probably a hundred times or more. When people say this, they mean to compliment Laity Lodge as an unusual place that fosters intimacy with God. For them, the barrier between earth and heaven does seem to become very thin at Laity Lodge. They have experienced God with more immediacy and intimacy when on retreat in the Frio River canyon than in their ordinary lives. In many cases, people have had life-transforming experiences at Laity Lodge through the presence and power of God’s Spirit. Thus, Laity Lodge would be an archetypal thin place.

Beginning today, I want to reflect a bit on the notion of thin places (sometimes called thin spaces). I don’t have any particular axe to grind here. Rather, I want to think about the idea of thin places, especially in light of Scripture. I want to consider what might make a place thin, and how this description might be helpful (or not).

As always I’m interested in your comments. What do you think of the language of “thin places”? Have you ever experienced something you might call a thin place? Where? What happened?

Stay tuned . . . .

The First Thin Place

Today, I want to begin some theological reflection on the idea of thin places. As usual, I will get into the theological issues by examining relevant biblical passages. My question, at this point, is “How does Scripture lead us to think about the idea of thin places?”

In case you missed my first post in this series, let me explain once again that thin place is a metaphor with Celtic Christian origins. A thin place, in this tradition, is a physical place where human beings experience God more directly. The metaphor assumes a worldview in which heaven and earth are, in general, separated by a considerable distance. But some places on earth seem to be thin in the sense that the separation between heaven and earth is narrowed. Thus, people sense God’s presence more readily in so-called thin places.

The metaphor of thin places does not appear in Scripture. That does not mean it’s unhelpful or theologically suspect. But, those of us who base our theology on the Bible will want to consider this metaphor in light of biblical revelation. Is the notion of a thin place something that can be derived from Scripture? Is it consistent with biblical teaching on how God reveals himself?

As we begin considering what Scripture has to say about thin places, we might well start at the beginning, in Genesis 1-3. There, we learn that God created heaven and earth, and that all of creation is good. We do not get the idea from these chapters that the world is divided up into godly places and ungodly places. There is no sanctifying of special spaces in the creation story. (There is, however, the setting aside of a special time, namely the seventh day. More on this later, I expect.)

From the opening chapters of Genesis we don’t learn much about the interaction of the first humans with God. In chapter 3, we do see how God comes to look for Adam and Eve after they disobeyed him, and how they communicate directly with him. But, because of their disobedience, they are cast out of the Garden of Eden. This suggests that their access to God is not what it once was. To use the metaphor of this series, we might say that Eden was the first thin place, and that human beings were expelled from this place because of their sin.

It would be mistaken, I believe, to think of Eden as the only thin place in the larger world. In fact, the Garden represents all of the created world. God’s purpose, it seems, was for all the world to be a thin place, a place where human beings experienced intimate and immediate fellowship with him. Eden represents the world before it was corrupted by sin, not a special place within the world where God is present.

Notice, however, what was supposed to have happened in the Garden of Eden according to God’s plan. Here, human beings were to be fruitful and multiply, to take care of the earth and manage it well. Here, human beings were to till the Garden that God had planted. In a phrase, the first thin place was a place of work as well as rest. The man and the woman would experience God as they did what God created them to do.

I think this point is worth our attention because, for the most part, we tend to associate thin places with rest and retreat. Most thin places are far away from the noisy, busy, relentless demands of daily life. People call Laity Lodge a thin place, for example, because they experience God in a powerful way while on retreat there. Ditto for other sanctuaries throughout the world. But I don’t think I’ve ever heard anyone refer to his or her workplace as a thin place (not counting those of us who work at retreat centers!). Our thin places tend to be places of rest, quiet, prayer, worship, reflection, and peace . . . not places filled with colleagues, to-do lists, emails, fax machines, computers, cell phones, etc. etc. This doesn’t surprise me, but it does make me wonder about thin places and their relationship to our ordinary, workaday lives. If the first thin place, arguably the thinnest place of all, was a place where people worked, what difference might this make in the way we think about work, God, and even thin places, for that matter? Or does the notion of thin places somehow lead us to expect that we’ll encounter God only when we’re away from the world of work and ordinary life?

Mt. Sinai as a Thin Place

If a thin place is defined as a place where God’s presence is known with particular immediacy, then there are several stunning thin places in Exodus . . . sort of. As we’ll see, they don’t exactly seem to fit the definition, though they certainly are thin.

Moses and the Burning Bush at the Mountain of God

In Exodus 3, Moses was tending his father-in-law’s flock when he came to “Horeb, the mountain of God” (3:1; Mt. Horeb is more commonly known as Mt. Sinai). “There the angel of the LORD appeared to him in a flame of fire out of a bush; he looked, and the bush was blazing, yet it was not consumed” (v. 3). When Moses started to investigate, the LORD himself called to him and told him not to approach, but to take off his sandals “for the place on which you are standing is holy ground” (v. 5). As Moses stood there, God revealed his purpose (to free the Israelites from their bondage in Egypt) and his name (I AM WHO I AM; I AM; Yahweh; all versions of the Hebrew verb “to be”) (3:7-14).

The Covenant and the Law at the Mountain of God

After the Israelites were delivered from Egypt, they journey into the same wilderness where Moses once encountered God in the burning bush. They camped in front of the mountain of God in what is called “the wilderness of Sinai” (19:2). Moses ascended the mountain, where God spoke to him, initiating the covenant with Israel (19:3-6). On the third day after this encounter, the Lord descended upon the mountain with fire, thunder, lightening, and smoke (19:16-19). Once again, he spoke to Moses, though this time “in thunder” (19:19). The Lord warned the people, through Moses, not to approach the mountain because it was holy (19:23-25). Then, in this context, God spoke the Ten Commandments (20:2-17). The people were afraid of the natural phenomena on the mountain, and kept their distance. Only Moses drew near to God (20:18-21) to receive God’s laws.

One of God’s first instructions to the Israelites was to build for him “an altar of earth” so they might present their offerings upon it (20:24). Then the Lord adds, “in every place where I cause my name to be remembered I will come to you and bless you” (20:24). At this point, the Israelites are not to build only one altar, whether at Mt. Sinai or any other place. Rather, they are to build altars in various places. Moreover, God promises to come to them in these places.

Reflections on Mt. Sinai as a Thin Place

If ever there were a thin place, it would have to be Mt. Sinai. After all, there the Lord revealed his purpose and name to Moses, a unique, watershed moment in the history of human interaction with God. Moreover, at Sinai, God revealed his awesome power to the Israelites, and, through Moses, established his covenant and law.

Yet in his instructions to the Israelites concerning altars, the Lord did not have them build a single altar at Sinai, as if this were some uniquely holy place. Rather, he commanded them to build altars “in every place” where he caused his name to be remembered (20:24). And the Lord promised to come and bless the Israelites in those places (20:24).

Yet in his instructions to the Israelites concerning altars, the Lord did not have them build a single altar at Sinai, as if this were some uniquely holy place. Rather, he commanded them to build altars “in every place” where he caused his name to be remembered (20:24). And the Lord promised to come and bless the Israelites in those places (20:24).

So Mt. Sinai was, on the one hand, one of the thinnest of thin places. Yet, on the other hand, it was not hallowed as a place that was somehow essentially thin. After the law was given at this location, we have no indication (to my knowledge) that Mt. Sinai continued to be a place of special prayer and pilgrimage for Jews. In time, of course, Jerusalem played that role. But, given what happened at Mt. Sinai, it is indeed striking that the place itself wasn’t regarded with awe as a unique place where one might encounter God. It wasn’t until several centuries after Christ that some Christians established St. Catherine’s Monastery at Mt. Sinai. (Photo: St. Catherine’s Monastery, with part of Mt. Sinai in the background.)

The sense we get from Exodus, at least to this point in the story, is that there can be thin places, but they don’t have to do with geography so much as God’s choice to make himself known there. After the time of revelation has passed, the former thin place retains none of its miraculous thinness.

More Thin Places in Exodus

In my last post, I examined Mt. Sinai as a thin place, that is, a place where God is experienced with unusual propinquity. (Now there’s a word I haven’t used or even thought of in about thirty years. “Propinquity” means “proximity.” It is the state of being physically close to someone or something.) If ever there was a thin place, this would have to be Sinai, because that’s where God first revealed himself to Moses in the burning bush, and then made his presence known in forming the covenant and giving the law to Israel. Yet, as I mentioned at the end of my last post, we have no reason to believe that the Israelites continued to regard Sinai as a special place where they might experience God in a special way. It had been a thin place, if you will, but did not have an ongoing status as a thin place.

The Pillar of Cloud and the Pillar of Fire

Other thin places in Exodus are similarly ambiguous with respect to their enduring thinness. After the Israelites began their journey from Egypt to the Promised Land, God led them by a pillar of cloud by day and a pillar of fire by night (Exod 13:21-22, for example). The text states that God was “in” the pillar in way that God is not ordinarily “in” the world. In fact, the Lord spoke to Moses from within the pillar (Exod 33:9). Once more, it would be hard to discount the thinness of these pillars. But, although they take up space in the world, they don’t inhabit one particular place. At best, one might say they are moving thin places.

The Tabernacle and Tent of Meeting

The Tabernacle dominates the latter portion of the Book of Exodus. It was a sanctuary for the Lord, a large, ornate, sophisticated tent structure. Because it was a tent, the Tabernacle was portable. It could move with the Israelites as they journeyed in the wilderness on their way to the Promised Land.

The Tabernacle, which was set up within a portable court, was itself divided into two sections. The larger section was the Holy Place, where various sacred items were housed. The smaller section was the Most Holy Place (traditionally, Holy of Holies), which contained the Ark of the Covenant. The Lord made his presence known in a unique and powerful way in the Most Holy Place.

Prior to the construction of the Tabernacle proper, which was sometimes called the “Tent of Meeting,” Moses had another, smaller Tent of Meeting in which he would meet with the Lord for personal conversation (Exod 33:7ff.). When the pillar of cloud descended on this Tent, the people would bow down to the ground, and the Lord would speak to Moses “face to face” (33:11).

When the official Tabernacle was consecrated, the Lord visited it in a most striking way. His glory filled the Tabernacle to such an extent that Moses was not able to enter it (Exod 40:34-36). The pillar of cloud and the pillar of fire rested upon the Tabernacle, signifying the powerful presence of God. The Israelites would remain in a given location until the pillar (or cloud) would be lifted from the Tabernacle as a sign that it was time to move on.

Reflections on the Pillars and Tents in Exodus

The Lord made himself known to his people in unusually powerful and sensible ways during the Exodus and thereafter. In a way, the pillars of cloud and fire, and the Tents of Meeting (both Moses’ and the official Tabernacle), were exemplary thin places. Except they weren’t places, strictly speaking. They were physical objects or realities that took up space and inhabited places, but didn’t remain in these places. What is perhaps most striking about these physical manifestations of God is their portability.

Yesterday, I noted that Mt. Sinai was a kind of thin place. God made his presence known there in an extraordinary way. But Sinai was not a thin place in the sense that it continued to be a portal to heaven in the eyes of the Jewish people. In today’s post, we have examined thin places that aren’t quite places. At least for a while, the pillars and tents were space-time realities through which God revealed himself. But they were not stationary places.

Moreover, it’s worth remembering that God’s presence in a place did not necessarily make it hospitable. When the Lord descended on Sinai with pyrotechnic splendor, the people were told to keep their distance, and that’s exactly what they wanted. And when God’s glory filled the Tabernacle, even Moses couldn’t enter it.

The Book of Exodus suggests that God makes himself known to us in places and spaces, but that there are not stationary thin places were God’s presence can regularly be experienced. Nothing in Exodus denies the existence of such places. But nothing in Exodus commends them, either.

Of course, as the story of Israel progresses, the Tabernacle becomes replaced by the Temple, which exists in a solitary location. In my next post in this series I’ll consider ways in which the Temple might be an exemplary thin place.

Excursus: Thin Places in the New York Times!

As you may know, I’m in the middle of a series of blog posts focusing on thin places. I’m trying to examine the concept of thin places from the point of view of biblical theology. So, as you might expect, I have thin places on my mind.

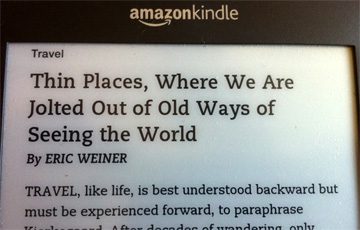

How surprised I was to see that thin places have also been on the mind of the New York Times. One of my readers added a comment (thanks Rhstigge!) alerting me to the article that I would probably have found on my own, but you never know. The title of the article as it appeared on my Kindle is “Thin Places, Where We Are Jolted Out of Old Ways of Seeing the World.” The online version of the Times has changed it to “Where Heaven and Earth Come Closer.”

How surprised I was to see that thin places have also been on the mind of the New York Times. One of my readers added a comment (thanks Rhstigge!) alerting me to the article that I would probably have found on my own, but you never know. The title of the article as it appeared on my Kindle is “Thin Places, Where We Are Jolted Out of Old Ways of Seeing the World.” The online version of the Times has changed it to “Where Heaven and Earth Come Closer.”

The article on thin places was written by Eric Weiner, author of the bestselling The Geography of Bliss and, most recently, Man Seeks God: My Flirtations with the Divine. Weiner describes himself as “a former foreign correspondent for NPR, a philosophical traveler—and recovering malcontent.” He adds, “For as long as I can remember, I’ve been a restless soul. When I was five years old, I ran away from home, determined to find what wonders awaited me around the corner. I’ve been looking ever since.” In terms of faith, Weiner is a seeker. He’s also an engaging and delightful writer.

I highly recommend that you read “Where Heaven and Earth Come Closer,” not because I agree with everything Weiner says, but because his ideas are well worth serious consideration. His discussion of thin places also helps to set up my effort to address them from a biblical perspective. There are many other perspectives on thin places, of course, including Weiner’s. But Christians, it seems to me, should always base their understanding of spiritual reality on biblical theology.

Though I encourage you to read all of Weiner’s article, I will print a few excerpts and add some brief comments of my own:

I’m drawn to places that beguile and inspire, sedate and stir, places where, for a few blissful moments I loosen my death grip on life, and can breathe again. It turns out these destinations have a name: thin places.

Notice that Weiner can talk about thin places here without reference to God (or the divine). Thin places are identified by their impact on a person’s feelings and experiences.

[Thin places] are locales where the distance between heaven and earth collapses and we’re able to catch glimpses of the divine, or the transcendent or, as I like to think of it, the Infinite Whatever.

This is a fairly classic definition of thin places, though Christians tend not to speak of God as “the Infinite Whatever.” I appreciate Weiner’s honesty here.

Travel to thin places does not necessarily lead to anything as grandiose as a “spiritual breakthrough,” whatever that means, but it does disorient. It confuses. We lose our bearings, and find new ones. Or not. Either way, we are jolted out of old ways of seeing the world, and therein lies the transformative magic of travel.

Notice that thin places, according to Weiner, are disorienting and not just comforting. When we are in them, we “are jolted out of old ways of seeing the world.” So, a thin place isn’t simply a cozy hug from God, according to Weiner. If you think about some of the thin places we’d examined so far, like Mt. Sinai, you’d have to agree with Weiner’s point.

So what exactly makes a place thin? It’s easier to say what a thin place is not. A thin place is not necessarily a tranquil place, or a fun one, or even a beautiful one, though it may be all of those things too. Disney World is not a thin place. Nor is Cancún. Thin places relax us, yes, but they also transform us — or, more accurately, unmask us. In thin places, we become our more essential selves.

Weiner doesn’t answer his own question here: So what exactly makes a place thin? Rather, he describes characteristics of thin places and their effect on us. He hasn’t yet tried to explain why this happens. Still, he is clear that thin places do more than simply make us feel good.

A park or even a city square can be a thin place. So can an airport. I love airports. I love their self-contained, hermetic quality, and the way they make me feel that I am floating, suspended between coming and going.

Here, Weiner parts company from what I have found to be a common understanding of thin places, which almost always sees them as set apart, as places of quiet and solitude. Notice that, for Weiner, what makes a place thin seems to be his experience in that place. There is nothing essential about the space that makes it thin.

You don’t plan a trip to a thin place; you stumble upon one. . . . To some extent, thinness, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder. Or, to put it another way: One person’s thin place is another’s thick one.

It appears that, for Weiner, no places are essentially thin. No places are necessarily thick. Thus, there really aren’t thin places in some sort of static way. (This sounds rather like what we saw concerning the pillars and the tabernacle in Exodus.)

Yet, ultimately, an inherent contradiction trips up any spiritual walkabout: The divine supposedly transcends time and space, yet we seek it in very specific places and at very specific times. If God (however defined) is everywhere and “everywhen,” as the Australian aboriginals put it so wonderfully, then why are some places thin and others not? Why isn’t the whole world thin?

Maybe it is but we’re too thick to recognize it. Maybe thin places offer glimpses not of heaven but of earth as it really is, unencumbered. Unmasked.

This is worth some serious thought. In many ways, I think Weiner approaches a biblical theology of thin places. Of course, God could always decide to make himself known more strikingly in a particular location (such as the temple in Jerusalem). But if God is everywhere, then perhaps thin places are not places where God is nearer to us. Rather, they may be places were we are able to perceive what is true always and everywhere. Maybe we become less thick and more attentive to God’s presence, which turns out always to be with us.

The Temple as a Thin Place

After God established the Tabernacle as “sanctuary” for the Israelites so that he might “dwell in their midst” (Exod 25:8), he continued to “camp” among his people in a temporary, portable dwelling. Many generations passed. Finally, David became the king of God’s people and centered his kingdom in Jerusalem. One day it dawned on David that he lived in a luxurious palace while the Lord only had a tent. So David resolved to build a permanent “house” for the Lord, a temple in Jerusalem.

At first, God did not seem too keen on the idea:

I have not lived in a house since the day I brought up the people of Israel from Egypt to this day, but I have been moving about in a tent and a tabernacle. Wherever I have moved about among all the people of Israel, did I ever speak a word with any of the tribal leaders of Israel, whom I commanded to shepherd my people Israel, saying, “Why have you not built me a house of cedar?” (2 Sam 7:6-7)

Nevertheless, the Lord choose, not David, but his son Solomon to “build a house for my name” (2 Sam 7:13).

This “house,” the Temple built in Jerusalem, was often referred to as God’s house, the place where he lived. For example:

For the LORD has chosen Zion;

he has desired it for his habitation:

“This is my resting place forever;

here I will reside, for I have desired it.” (Ps 132:13)

Yet the Jewish people understood that the Lord did not literally live in the Temple. At its dedication, when the glory of the Lord filled the temple, Solomon said, “The LORD has said that he would dwell in thick darkness. I have built you an exalted house, a place for you to dwell in forever” (1 Kings 8:12-13). But then, several verses later, Solomon adds, “But will God indeed dwell on the earth? Even heaven and the highest heaven cannot contain you, much less this house that I have built! . . . Hear the plea of your servant and of your people Israel when they pray toward this place; O hear in heaven your dwelling place; heed and forgive (1 Kings 8:27, 30).

For Jews, the Temple represented God’s presence with them. Going to the Temple was a solemn occasion for prayer and sacrifices, but also a joyous occasion for celebration and feasting. Of course, only priests were able to enter the actual sanctuary, with its Holy Place and Most Holy Place (literally translated from Hebrew as “holy of holies”). In fact, the high priest alone was able to enter the Most Holy Place, and only once a year, on the Day of Atonement.

The Temple represented the Lord’s unique covenant relationship with Israel. He was their God and they were his people. By the time of Jesus, the Temple in Jerusalem, built by King Herod the Great, included several outer courts. The furthest out was the Court of the Gentiles. Non-Jews were included in the Temple to an extent, but kept out of the courts reserved only for Jews, including the inner sanctuary.

Yet, certain prophetic passages envision a time when the Gentiles would come to the Temple:

In days to come

the mountain of the LORD’S house

shall be established as the highest of the mountains,

and shall be raised up above the hills.

Peoples shall stream to it,

and many nations shall come and say:

“Come, let us go up to the mountain of the LORD,

to the house of the God of Jacob;

that he may teach us his ways

and that we may walk in his paths.”

For out of Zion shall go forth instruction,

and the word of the LORD from Jerusalem” (Micah 4:1-2).

Other prophetic texts shows that this is not just something the Gentiles desire, but something willed by the Lord himself:

And the foreigners who join themselves to the LORD,

to minister to him, to love the name of the LORD,

and to be his servants,

all who keep the sabbath, and do not profane it,

and hold fast my covenant—

these I will bring to my holy mountain,

and make them joyful in my house of prayer;

their burnt offerings and their sacrifices

will be accepted on my altar;

for my house shall be called a house of prayer for all peoples.

(Isa 56:6-7)

Thus, Jewish eschatology envisioned a day when all peoples, not just the Jews, would come to the Temple for prayer, sacrifices, instruction, and celebration.

Reflections on the Temple as a Thin Place

In Exodus, the possible thin places always seemed to be lacking something. Mt. Sinai was a very thin place, but only in unusual revelatory moments. The Pillars of Cloud and Fire and the Tabernacle were astounding space-time signs of God’s presence, but they weren’t places in the ordinary sense since they were intentionally portable.

The Temple in Jerusalem is a closer analogy to a thin place. It was one place and it didn’t move. This place was said to be God’s own house, though it was understood that God didn’t actually live there. The Temple helped people get right with God (through sacrifices) and be directed by God (through teaching) and communicate with God (through prayer) and enjoy God (through celebrations).

The Temple was not, however, a place of worship like a synagogue or church sanctuary. Nor was it a quiet place for retreat, at least not in the courts where ordinary folk were welcome. The Temple, by its very design, kept people away from its holiest places, the places where God was said to dwell and where priests alone could enter. Yet common people surely experienced God’s presence in the Temple courts, and in this sense those courts constituted a thin place. Thus, people looked forward to coming to the Temple, as Psalm 84 reminds us:

How lovely is your dwelling place,

O LORD of hosts!

My soul longs, indeed it faints

for the courts of the LORD;

my heart and my flesh sing for joy

to the living God. . . .

For a day in your courts is better

than a thousand elsewhere.

I would rather be a doorkeeper in the house of my God

than live in the tents of wickedness. (Psalm 84:1-2, 10)

The existence of the Temple shows that God can and does, at times, identify closely with a certain place, making his presence known there in a powerful way. But this truth is reshaped in light of Christ. I’ll explain further in my next post in this series.

Jesus and Thin Places

In my last post in this series, I suggested that the Temple in Jerusalem was the paradigmatic thin place in the Old Testament. The Temple was considered God’s house, metaphorically speaking, the chief place in which his presence lived on earth. Unlike the Tabernacle, the Temple existed in one place, a place to which thousands of Jews made pilgrimage each year so they might experience God in a deeper way.

It’s important to note, however, that the Temple was not a thin place in the sense of a retreat center or idyllic garden of natural beauty. The Temple courts were places of busy crowds, especially during times of pilgrimage. The sanctuary of the Temple was off limits to non-priests, and the holiest place of all was entered only by the high priest only one day a year.

Jesus and the Temple

When we turn to the New Testament, we find continued respect for the Temple. Jesus’ parents, for example, presented him in the Temple in faithfulness to the law (Luke 2:22-35). They made pilgrimage to the Temple every year at Passover (Luke 2:41). Jesus echoed Isaiah in regarding the Temple as a house of prayer (Luke 19:46; Isa 56:7) and he frequently made pilgrimages there.

However, Jesus also did and said things that seemed to undermine the sanctity of the Temple. His so-called “cleansing of the Temple” was not just a condemnation of its commercialization, but also a stab at the heart of its sacrificial functioning. Moreover, by forgiving sins under his own authority, Jesus’ implied that the Temple and its sacrifices were not necessary any longer. Further, by speaking of himself with Temple imagery, Jesus also suggested that he was in some way replacing the Temple (John 2:19-22).

Moreover, in John 4, when Jesus encountered a woman at a well in Samaria, he critiqued the notion that certain physical places are holier than others. Jews believed that God was most present in the Temple in Jerusalem. Samaritans favored Mt. Gerizim as the true holy place. When the woman mentioned this controversy to Jesus, he responded:

“Woman, believe me, the hour is coming when you will worship the Father neither on this mountain nor in Jerusalem. You worship what you do not know; we worship what we know, for salvation is from the Jews. But the hour is coming, and is now here, when the true worshipers will worship the Father in spirit and truth, for the Father seeks such as these to worship him. God is spirit, and those who worship him must worship in spirit and truth.” (John 4:21-24)

Now, of course Jesus is not weighing in on the notion of thin places per se. But it is interesting that he discounts the value of particular places are more or less optimal for worship. What really matters is not where we are when we want to encounter God, but rather the openness of our spirits (or the presence of the Holy Spirit) and the truthfulness of our understanding of God.

Jesus and Thin Places

In fact, Jesus, as the Incarnate Word of God, was “God’s house,” if you will, in an altogether new sense. In Jesus, God came to earth to reveal himself more immediately and powerfully than in the Temple. Though the metaphor begins to break down at this point, one might say that Jesus was the ultimate thin place. Like the Tabernacle, he was not anchored to any one location, however. Yet as he moved around, God was exceptionally present wherever Jesus was present. Thus, Jesus could say to those who were with him, “The Kingdom of God is already among you” (Luke 17:21).

Given that Jesus was God in human flesh, we might think that places no longer matter at all when it comes to our relationship with God. But, surprisingly enough, Jesus himself seemed to seek intimacy with his Heavenly Father in special places. In Mark 1:35, for example, we read: “In the morning, while it was still very dark, he got up and went out to a deserted place, and there he prayed.” As his popularity increased, Jesus “would withdraw to deserted places and pray” (Luke 5:16). We have no reason to believe that Jesus thought of certain places as essentially thin. But it does seem that he found benefit in getting away from the distractions of ordinary life in order to pray.

The example of Jesus suggests that certain places can help us pray more faithfully, and perhaps even experience God more intimately. These places are “deserted” – free from the bustle of ordinary life. Notice, however, that Jesus appears to have many such thin places. We have no evidence that he frequented one or two particular spots. We do not find in Jesus the idea that certain particular places are necessarily or essentially thin. Rather, any place of quiet and distance from civilization can become a thin place if one goes there to spend an extended time with the Lord.

Moreover, if Jesus was truly the Word of God Incarnate, then he is without question the thinnest of all thin places. In fact, in Jesus, the barrier between heaven and earth wasn’t just thin, it was completely non-existent. Heaven, if you will, broke through the barrier and came to be present on earth. This basic fact of Christian faith radically influences our understanding of thin places, or at least it should. It suggests that if we wish to experience God in a genuine and intimate way, then this will happen in and through Jesus. Though he is not here with us in the flesh, he is with us in spirit, or, better yet, in the Spirit. The good news of Christianity is not that certain places are thin, but that God has come to us in Jesus, and that we can experience God through Jesus and the Spirit.

The Church as a Thin Place

In my last post in this series, I examined how Jesus impacts our understanding of thin places. If a thin place is a location where God’s presence can be experienced with unusual intensity, then Jesus himself was the ultimate thin place. Yet, as I noted in my last post, Jesus did withdraw from people to pray, suggesting that one’s location may have something to do with one’s relationship with God. Deserted places, free from noise and earthly demands, often can serve as thin places in our lives, even as they did in the life of Jesus.

Yet Jesus did not establish one or more sacred places to serve as portals to the divine from his followers. It is quite curious, actually, that key places in Jesus’ life did not take on sacred status among the first disciples. We have no reason to believe, for example, that they frequently returned to Jesus’ birthplace, or his tomb, or his own desert “retreats” in order to pray. This is really quite extraordinary, given the tendency for religious people, including Christians, to venerate sacred places and visit them as if they were passages to the divine.

The fact that the early Christians didn’t have designated sacred places was perplexing to people in the Greco-Roman world. Virtually every recognized religion in this culture was identified by its holy places, people, and things. The holy places were the temples where people communed with the gods. The holy people were the priests, who handled the holy things, the sacrifices offered to the gods. But the early followers of Jesus met in houses or public gathering spaces and didn’t construct special buildings until at least two centuries after Jesus’ death and resurrection. When they did, these structures were not considered to be temples, at any rate.

There are solid theological reasons for the absence of temples among the early Christians. The very first Christians continued to worship in the Temple in Jerusalem, but did not feel compelled to build a replacement when the Temple was destroyed in AD 70. They knew that, in all the ways that truly mattered, Jesus had replaced the Temple. They could receive divine forgiveness through faith in Jesus, not through offering the appropriate sacrifices in the Temple. They could experience the presence of God, not by going to some special place, but through faith in Jesus and through the Spirit given by Jesus to those who trusted in him.

Moreover, the early Christians thought of themselves as the new Temple. In 1 Corinthians 3:16-17, the Apostle Paul responds in this way to those who would threaten the unity of the Corinthian church: “Don’t you realize that all of you together are the temple of God and that the Spirit of God lives in you? God will destroy anyone who destroys this temple. For God’s temple is holy, and you are that temple.” Three chapters later, Paul will use a similar metaphor in describing the body of the individual Christian as a temple of the Holy Spirit (6:19). But in 3:16-17, the temple is the church. In the church, God makes his presence known through the Holy Spirit, who dwells in and among the gathered believers in Jesus.

So the first Christians did not build temples because Jesus had done, once and for all, part of what temples were supposed to do. Jesus opened up the way to intimate fellowship with God through himself. When Jesus was no longer present on earth, he sent his Spirit upon his people. From Pentecost onward, the church was to be the thin place of the world. In the gathering of God’s people, God’s presence would be available to all. And, as the church scattered into the world, it permeated the world with human “thin places,” so all people might experience the grace, love, and presence of God through his people.

At least this was the theory. It’s well know that the church hasn’t always played its thin place role very well. In my next post I want to suggest some ways the church can be a more consistently effective thin place in the world.

The Church as a Thin Place: Some Implications

In my last post in this series, I suggested that, from the point of view of the New Testament, the church is to be the world’s most significant thin place when Jesus is no longer present on earth in the flesh. To put it differently, in the time after the ascension of Jesus and the descent of the Holy Spirit, God has chosen to make himself known most of all through the church. Of course God is not limited in this way and can reveal himself in a plethora of means and places. But, in a very real sense, the church is to be the world’s preeminent thin place.

Of course, the “thin place” metaphor fits awkwardly here because the church isn’t really a place. It’s not even a vast collection of places so much as a vast community of people who often gather in a vast number of places. When I speak of the church as a thin place, I mean that God makes himself known through his people, both as they are gathered and as they are scattered in the world. Thus when my church in Boerne, Texas gathers for worship on Sunday, we are (or should be, at any rate) a thin place. When we go out into the world, we become several hundred thin places, at least in potential. We, and the other Christians in our town, are portable thin places, not unlike the Tabernacle in the Old Testament or, if you prefer, Jesus himself.

I wonder what would happen if we began to think of ourselves in this way. What do you think would happen if you thought of yourself as a thin place in the following circumstances?

• Interacting with your colleagues at work;

• Doing chores with your children;

• Having a leisurely dinner with your spouse or best friend;

• Talking with the clerk in the local convenience store;|

• etc. etc. etc.

What difference might it make if churches thought of their corporate life as a thin place, a place where people might interact in a profound way with the living God?

Let me answer this question with one quick thought. First, if churches saw their corporate life as a thin place, perhaps they’d have more times of quiet and even silence when they gather. When I was the Senior Pastor of Irvine Presbyterian Church, our worship services almost always included times of silence. Some were complete quiet; others were “covered” by instrumental music. I appreciated these quiet times and used them to commune with the Lord. There were “thin times” for me, if you will.

Then, in 2000, I took a three-month sabbatical. During that time I visited many churches in the Orange County area. These were all impressive. Most were larger than Irvine Presbyterian. A few were megachurches. All included top-notch music and excellent preaching. But none – literally, none – of these churches left time for quiet in their worship gatherings. They were joyous, exuberant, God-honoring, and consistently loud.

Now I am not suggesting that thin places have to be quiet. God can surely make himself known in the midst of and even through noise. (Remember the epiphany on Mt. Sinai, for example: thunder, lightening, trumpet blasts, etc.) But, surely, there should be a time for God’s people to be quiet together so that they might hear the “still, small voice” of the Lord, both individually and corporately.

A church that thought of itself as a thin place would, I believe, become more intentional about creating times of quiet for people. It might include such times in corporate worship on a regular basis. Or it might host an evening prayer service with lots of quiet. Or it might sponsor a silent retreat. Or it might construct a prayer garden where people could wait on the Lord. Or . . . you name it (literally, if you wish, by leaving a comment).

Tomorrow I’ll have more to say about some practical implications of a church as a thin place.

The Church as a Thin Place: Dreams and Visions

In yesterday’s post, I began reflecting in a more practical way on the church as a thin place. Today I want to continue these reflections, sharing a few of my dreams and visions for the church.

The Church as a Place of Prayer for All Peoples

In the Old Testament, the Temple was the supreme place of prayer for the Israelites. But in some prophetic passages, a more expansive vision appeared. Consider, for example, Isaiah 56:7, which speaks of the Temple as a “house of prayer for all peoples.”

The church, it seems to me, should be such a place, not just accidentally, but intentionally. Yes, I know most churches are theoretically open to all kinds of people. But, in fact, most churches do not make an effort to invite people to pray with them.

I struggled with this fact as Senior Pastor of Irvine Presbyterian Church. Along the way, my fellow leaders and I made some changes that were meant to welcome all people to join us in prayer. For example, at some point we realized that we prayed The Lord’s Prayer every week, but nowhere provided the text for those who didn’t know. So we began printing and projecting The Lord’s Prayer for the sake of our guests. We also closed every service with an invitation for people to come forward for prayer with an elder or deacon. During my sixteen years at Irvine, we prayed for thousands of people in this way.

Daily Prayer

But I had other dreams, dreams that I was not able to realize when God called me away to Texas. One of these dreams was to do as many more liturgical churches do, and offer morning and evening prayer every day. Our form of prayer wouldn’t necessarily be as structured as one would find in a Catholic or Episcopal church. In fact, I thought it would be interesting to vary the menu quite a bit. Yet, with utter consistency, we would offer a short prayer service very day, perhaps at 7:00 in the morning and 7:00 in the evening. This would be intended, not just for church members, but for people in the community. We would say to our neighbors: “If ever you feel like you want to pray, or if every you need somebody to pray for you, or if you just want to sit in quiet while others are praying, come join us. You are always welcome. We are here for you because God is here for you.”

Adding twelve prayer services a week (Monday – Saturday) would have taken some organizational work, but it would have been well worth it. I figured that the pastors (we had three and a half pastors at that time) would lead some of these prayer times, but not all. Others would be led by lay leaders, including non-ordained staff, elders, deacons, and others. We’d always have at least two people present, preferably a man and a woman. The prayer time would last around fifteen minutes, though people would be invited to remain for quiet prayer if they wished.

I tried to get my fellow leaders to be excited about this idea, but, frankly, we had too much going on to give this vision the attention it needed. I sometimes thought that offering prayer of this sort should be at the heart of any church’s mission, but I didn’t press the point, right or wrong. It’s certainly easy to see how such a practice of daily prayer would help a church be a thin place, a place where people encounter God.

A Prayer Chapel

I had also hoped that, someday, Irvine Presbyterian Church would build a prayer chapel that could be open all day. This would be different from the chapel that was part of our master plan, a building that would be suitable for small weddings, memorial services, and so on. The prayer chapel would be quite small, designed so that it could remain unlocked without continual supervision. Given the weather in Southern California, this could have been a prayer garden, though we didn’t have much space for something like this.

I realized that a prayer chapel such as I envisioned would create lots of challenges, since it would be open and usually unsupervised. But I had hope that, in time, we could build such a space and offer it to our community as a place of quite prayer. Many on our church building committee were favorable to this idea.

Programmatic realities took precedence, so we built an administration building with a youth center instead. I think this was the right choice, and I supported it completely. But I never gave up the hope that, someday, we might build a place of prayer for our community, either a chapel or a garden.

The “Holey” Church

Today, my dreams and visions for the church have more to do with what the church does while dispersed in the world than with what it does while gathered together for prayer, worship, discipleship, and service. I don’t in any way wish to disparage the importance of the church gathered. But, in my role with Laity Lodge, I’m more invested in the church scattered.

Thus I want to revisit something I wrote about in my last post, the vision of the church as a collection of thin places out in the world. If you think along the lines of the thin place model, with the earth and heaven being separated by some sort of thick barrier, then the people of God are millions of thin places in the barrier. Or, to mix metaphors, we are like holes in the Swiss cheese barrier between the earthly and the divine. The church would be, pardon the bad pun, a “holey” church, a church of holes through which God’s presence would be experienced.

Thus I want to revisit something I wrote about in my last post, the vision of the church as a collection of thin places out in the world. If you think along the lines of the thin place model, with the earth and heaven being separated by some sort of thick barrier, then the people of God are millions of thin places in the barrier. Or, to mix metaphors, we are like holes in the Swiss cheese barrier between the earthly and the divine. The church would be, pardon the bad pun, a “holey” church, a church of holes through which God’s presence would be experienced.

So, though I’m all in favor of churches providing spaces for people to experience God, I’m even more excited about the idea of Christians living in the world in such a way that people don’t even have to go to a church facility or a retreat center to sense the presence of God.

In my next post I want to offer some theological reflections on the notion of thin places, and share some hesitations I have about this metaphor.

Thin Places: Theological Reflections and Hesitations

Today I want to wrap up this series on thin places by offering some theological reflections and hesitations. If you’re joining this series late in the game, let me say that the language of “thin place” is a Celtic metaphor that describes physical locations in which God is especially present. A retreat center or a quiet sanctuary would be obvious examples of potential thin places. This description has become increasingly popular in the last couple of decades because of the influence of Celtic spirituality in America.

In this series, I have sought to examine the notion of thin places from a biblical perspective, beginning with the original thin place, the Garden of Eden, and then moving through the Old Testament (Mt. Sinai, pillars of cloud and fire, the tabernacle, the Temple in Jerusalem). From a New Testament vantage point, Jesus serves as the ultimate thin place, the “place” in which God’s presence is revealed most directly. Those who follow Jesus carry on his thin-place mission. Thus the church should be a thin place, not only for its members, but also for the people to whom it has been sent.

Of course most of the biblical thin places aren’t exactly places in the literal sense. The pillars of cloud and fire, the tabernacle, Jesus, and the church occupy places but are not limited to any particular place. They are movable place-fillers rather than places, per se. The notion of thin places, though not necessarily contradicted by Scripture, cannot be easily derived from it. In fact, as I mentioned earlier in this series, part of what made Christianity so confusing in the first-century Roman world was its lack of sacred places. Unlike very other religion, it didn’t have temples.

This was not just an accident. The early Christians believed that Jesus was God in human flesh. Through his death, he offered the once and for all sacrifice for sin, so that there was no longer a need for a temple and its sacrifices. Moreover, the early Christians believed that the Spirit of God had been given to them. The bodies of individual Christians were the temples of the Holy Spirit, as was the gathered church (so 1 Corinthians 6 and 3). So when a bunch of Christians got together in a house, as they often did in the first century, this was a sacred place, or a thin place, if you prefer.

In light of the New Testament, it’s hard to find much support for the notion of thin places in the strict sense. If we use the phrase “thin place” as a metaphor, and don’t invest it with too much reality, then I don’t have a problem with this language. But if we start reifying thin places, if we believe that God has actually chosen certain geographical locations as special portals into heaven, then we risk misunderstanding God and his way of making himself known. After all, the Word became flesh, not a place. And the Spirit of God dwells in human beings, not in sacred buildings or mystical places.

Moreover, most so-called thin places tend to be secluded, either by physical distance or by thick walls or both. Thin places are generally quiet and isolated, unlike most of the places we live. It is certainly true that in places like this we can be more attentive to God. Remember that Jesus himself withdrew from the crowds in order to spend time with his Father in deserted places. But we make an unfortunate error is we start thinking that God is more present in such isolated places than in all other places.

To be sure, God makes his presence known in a particular way when we are quiet and alone. But God also makes his presence known through the loud praises of his people. And God makes his presence known when his people build houses for the homeless in his name. And God makes his presence known when a Sunday School teacher loves a bunch of rowdy three-year old boys. And God makes his presence known when somebody extends a word of sympathy to a colleague who is going through hard times. And God makes his presence known when a boss chooses to offer grace to somebody who messed up on the job. And so on and so on.

Perhaps the greatest problem in the thin place metaphor, apart from its lack of biblical support, is the worldview it assumes and the implications that flow from this worldview. A thin place is, by definition, an exception to the rule. And the rule states that this world and the heavenly world are separated by a thick barrier. God is on the other side of the barrier, mostly separate from the world, except for unusually thin places in which he makes himself known. This worldview is not uncommon, but it is not biblical. Scripture teaches us to see God as much more involved in this world than the thin place metaphor assumes. Thus, I am hesitant to use the this metaphor, because I fear it reinforces incorrect and unhelpful ways of seeing God and the world.

Now, as you might guess, I think we need places of quiet retreat, places where we can pray without interruption, places where we are more apt to hear God. From my years as Senior Director of Laity Lodge, I learned that such a place can help us to experience God more intimately and truly. But one of the main reasons we go on retreat is so that we might learn to be more attentive to God’s presence in our ordinary lives. We take time away from work, for example, so we can learn to experience God more consistently in our workplace.

I also acknowledge, quite gladly, that God does make himself known in certain places with extraordinary intimacy and regularity. People do in fact encounter God at Laity Lodge more often than they do at Garven Store, an establishment near Laity Lodge where you can buy jerky, biker gear, and beer. I even think I know some of the reasons people meet God at Laity Lodge. It’s exceptionally quiet and stunningly beautiful. God’s truth is taught there week in, week out. Those who founded Laity Lodge and those who work there are committed to treating each guest with striking hospitality. (Notice, it isn’t just the place, but the people in the place who make a difference.) Moreover, Laity Lodge has been dedicated to God ever since its founding. He uses this space, in part, because those to whom he entrusted it gave it back to him for his purposes. But one of the things I love about Laity Lodge is the fact that our founder, Howard E. Butt, Jr., believes that our experience of God at the Lodge is meant to help us experience and serve him more effectively in the world.

I also acknowledge, quite gladly, that God does make himself known in certain places with extraordinary intimacy and regularity. People do in fact encounter God at Laity Lodge more often than they do at Garven Store, an establishment near Laity Lodge where you can buy jerky, biker gear, and beer. I even think I know some of the reasons people meet God at Laity Lodge. It’s exceptionally quiet and stunningly beautiful. God’s truth is taught there week in, week out. Those who founded Laity Lodge and those who work there are committed to treating each guest with striking hospitality. (Notice, it isn’t just the place, but the people in the place who make a difference.) Moreover, Laity Lodge has been dedicated to God ever since its founding. He uses this space, in part, because those to whom he entrusted it gave it back to him for his purposes. But one of the things I love about Laity Lodge is the fact that our founder, Howard E. Butt, Jr., believes that our experience of God at the Lodge is meant to help us experience and serve him more effectively in the world.

If you want to use the thin place metaphor, then perhaps you should say that the purpose of thin places is to help us realize that all places can be thin. Or, better yet, perhaps the purpose of a thin place is to train us to make the other places in our lives thinner. Moreover, when we realize that the Spirit of God dwells within us, we will come to believe that we are called to be thin places, as God makes his presence known through us.