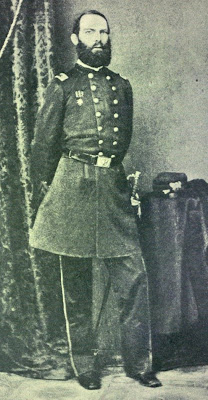

The Battle of Stones River, which took place on December 31, 1862, in Tennessee, was a hard-fought Union victory. But for the federal commander, Major General William S. Rosecrans, it came at a personal loss, the death of his aide and friend, Lieutenant Colonel Julius Garesché. A respected officer, Garesché had recently left a desk job for field service. When news of his death reached Washington, one general said it was “equivalent to a defeat, for Garesché was worth an army!” Another general described him as the

The Battle of Stones River, which took place on December 31, 1862, in Tennessee, was a hard-fought Union victory. But for the federal commander, Major General William S. Rosecrans, it came at a personal loss, the death of his aide and friend, Lieutenant Colonel Julius Garesché. A respected officer, Garesché had recently left a desk job for field service. When news of his death reached Washington, one general said it was “equivalent to a defeat, for Garesché was worth an army!” Another general described him as the

ideal of a perfect Christian gentleman… a gallant, daring soldier in the field; a wise counselor, and many times consulted by the President, especially in the selection of Officers for high command in the army.

A career soldier, Garesché was also an extremely active Catholic layman. A daily Mass-goer who helped build churches where he was stationed, Garesché wrote for the Catholic press, helped the poor and visited the sick, and impressed many with his good example.

Descended from two distinguished French families that emigrated to America, Julius Peter Garesché was born in Cuba, where his diplomat father was stationed. Although baptized Catholic, it played little part in his upbringing. It was while attending the Jesuits’ Georgetown College in Washington, D.C., that he embraced his Catholicism wholeheartedly. An exceptional classical scholar, throughout his life he read and translated Latin for pleasure.

Although classmates assumed he would become a priest, Julius wanted a military career. In 1837, he was appointed to West Point. The sole Catholic cadet, he was highly regarded for his intelligence and character. One classmate commented: “I do not believe he had an enemy in the Corps of Cadets.” Another remembered “the perfect purity of his character… but few could enter more heartily into a game of football.”

For five years after his graduation in 1841, Garesché was assigned to East Coast garrisons. In 1843, he was contacted by Lieutenant William S. Rosecrans, who was a year behind him at West Point. Rosecrans was interested in Catholicism, and their conversations played an important role in his conversion. A few years later, they formed an association for Catholic officers, dedicated to Jesus’ Sacred Heart.

During the Mexican War, which he considered “of doubtful justice and forced upon a weak and inferior State” (an opinion Ulysses S. Grant shared), Garesché was appointed an adjutant (administrative officer) in northern Mexico. At this time his brother Frederick joined the Jesuits, a step he wished he “had the courage to take.” After making a retreat, however, he decided to continue as a soldier.

He also decided to marry. In 1848 he asked his mother to find him a wife, which one historian notes “was the custom among aristocratic Franco-Americans.” Six weeks after meeting Mariquitta de Coudroy de Lauréal, age eighteen, they were married. The marriage was happy, producing eight children. Garesché was soon assigned to Brownsville, Texas, where he stayed for several uneventful years.

There he helped build a church. He served Mass every Sunday in full dress uniform. In 1851, through a priest friend’s influence, he was named a Knight of St. Sylvester, a papal honor for laymen. In 1855 he was promoted to Captain and assigned to Washington in the Adjutant-General’s Office. He also wrote for two Catholic periodicals, The Freeman’s Journal and Brownson’s Quarterly Review, under the name “Catholicus.”

In 1859, he helped organize Washington’s St. Vincent De Paul Society (a group founded to help the poor), serving as Vice-President. In his spare time he worked on a religious treatise that was never published. Garesché seems to have had a sense of humor about his faith. He once told a Protestant officer: “We Catholics have an advantage over you Protestants; for when we lose anything, we go to a little saint who assists us to recover it.”

When the war broke out, Garesché was promoted to Major. A strong “Union man,” he opposed slavery as unjust. President Lincoln offered him a general’s commission several times, but Garesché refused until he had “active service at the front.” For much of the time, he ran the adjutant-general’s office by himself. In July 1862, he was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel.

In October his friend Rosecrans, now a general, took over the Army of the Cumberland in Tennessee. He wanted Garesché, whom he “long esteemed and admired,” for his chief of staff. Historian James McPherson describes Rosecrans as a devout Catholic who loved arguing theology with his staff officers into the night over cigars and whiskey. Future President James Garfield, who served under him, described him as “a Jesuit of the highest type of Roman piety.”

Major General William S. Rosecrans (seated, fourth from left) with his officers. Brigadier General James A. Garfield is seated to the right of Rosecrans.

Major General William S. Rosecrans (seated, fourth from left) with his officers. Brigadier General James A. Garfield is seated to the right of Rosecrans.

On November 5th, Garesché was appointed to Rosecrans’ staff. Family tradition holds that he had a premonition of being killed in his first battle, but that he would be “spiritually prepared.” He left his family wondering if he would ever see them again. He asked Mariquitta to see the children studied “their catechism well.” Mariquitta responded: “Every evening we all say a Decade of Beads, asking of the Blessed Virgin to protect you and return you soon to our caresses.”

On the morning of December 31st (the Feast of St. Sylvester), the Army of the Cumberland prepared for battle. Colonel Garesché received Communion alongside Rosecrans, who “never saw him look half so handsome or animated.” Riding together into battle, a cannonball decapitated Garesché. After the battle, Brigadier General William B. Hazen was able to identify his friend’s corpse from two items that formed a cornerstone of Garesché’s life, his West Point ring and a pocket copy of The Imitation of Christ.

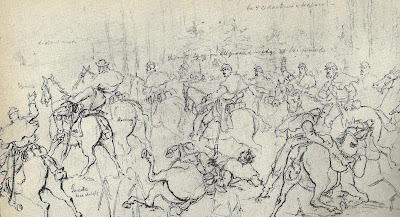

Artist Henri Lovie captured the moment of Colonel Garesché’s death at Stones River.

Artist Henri Lovie captured the moment of Colonel Garesché’s death at Stones River.

Julius Garesché’s body was brought back to Washington for a funeral Mass at the Jesuits’ St. Aloysius Church. There he was eulogized as “this faithful and devout Catholic soldier.” In 1892, historian John Gilmary Shea called him “perhaps the noblest type of the American Catholic soldier we have ever had.” Two of his daughters became Carmelite nuns in St. Louis after his death.