Long ago (though not quite as long ago as the liberal arts adventure I wrote about last time) when I was in seminary, I sought, like many seminary students, to grow in grace and holiness.

I had by that time read Charles Williams (it was part of my liberal arts education! I found The Greater Trumps in my college bookstore!), and knew of his theology that grace and holiness can be pursued in two ways: the Way of Affirmation and the Way of Negation. I need to make a caveat here that Weird Stuff has come out about Williams since The Greater Trumps bowled me over as a teenager. Nevertheless, I think that his basic insight that the Christian tradition has preached both of these approaches to the beatific vision is a sound one. (He referred to them as “This also is Thou” and “Neither is this Thou.”)

It so happens that my spiritual formation as a child and young person and especially in the seminary context was very much on the “Neither is this Thou” side of things. Wesleyan-Arminian types are not the only folks with ascetic approaches to sanctification, of course, but it is a strong component of the tradition. Holiness of heart and life comes to you in the Wesleyan tradition by doing stuff – practicing the means of grace, doing works of mercy – but also by not doing stuff. Wesley, after all, is the guy that was able to turn hedonism into medical prescription in his abridgement of a tract by a Dr. Cadogan:

I myself was ordered by Dr. Cheyne, (not the warmest advocate for liquors,) after drinking only water for some years, to take a small quantity of wine every day. And I am persuaded, far from doing me any hurt, it contributed much to the recovery of my strength. But it seems, we are to make a pretty large allowance for what the Doctor says on this head; seeing he grants, it will do you little or no harm to take “a plentiful cup now and then.” Enough, enough! Then it will certainly do you no harm, if, instead of drinking that cup in one day, (suppose once a week,) you divide it into seven, and drink one of them every day.

I learned much in seminary – how to read the Bible well, how to preach, how to worship, how to counsel. My love for history, already stoked by that famous liberal arts education, grew and blossomed into an eventual career of speaking about church history in everyday language. (Here, and here, for example.) But it was also in many ways a dark time. I came up against the limits of my own soul, and I found myself utterly unable to believe that Jesus loved me. It was a classic Dark Night of the Soul.

The remedy for this which I was recommended was the Way of Negation. God would strip away from me everything that was not of him, I was told, and when I reached the end of my rope and everything I had gained was lost, I would find that he would walk with me in the darkness. I used to thrill to the beautiful lines from the great hymn “Be Still, My Soul:”

Be still, my soul: thy Jesus can repay

From His own fullness all He takes away.

In one sense, I suppose that’s true. I am, after all, still here, and I got some of the things I deeply sought twenty-five years ago (most particularly, a husband.) But fast-forward all the way from the mid 1990s to last month, when we were rehearsing that hymn as a choir anthem at church. I got to that verse, and I thought about the last few years in my own history and the history of the world, and I thought, in the inner sarcastic meme voice that I’ve picked up from my Gen Z children, Well then. Does he now?

The ultimate promise of the Way of Negation – at least in the form I picked it up, which was more Wesley than Williams – was that when you gave up stuff for Jesus you would get stuff back. During the first week of chapel at seminary, one of the speakers was missionary Jackie Pullinger, who talked of giving up a promising academic and musical career to go to Hong Kong and minister to drug addicts. I, who had always dreamed of a promising career of that sort, was devastated. I called my mother in tears. Pullinger said that she had had to give up or sell her expensive oboe as part of her missionary journey. But, she said, God provided a much better oboe later. Where, I wondered as I fought my way through the dark night, was my oboe?

I bought an oboe pin for my mom when I graduated from seminary as a sign that God was in the much better oboe business. But Mom never really got any promised oboe. She was a tremendously talented musician with an inquisitive theological mind, but her physical health was poor and her mental health suffered from what I now realize was undiagnosed autism and ADHD to go along with the diagnosed bipolar disorder, and she died 14 years ago at the age of 68. She no longer suffers, but she lived a life where pretty much everyone except my dad misunderstood her, and she’s missed a whole heck of a lot that I would have preferred to have her around for.

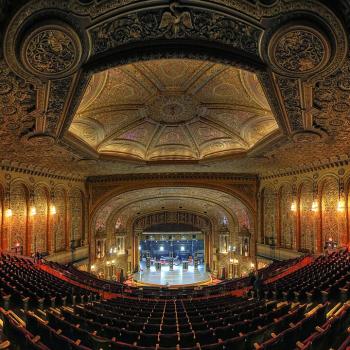

So when “Be Still, My Soul” came up at rehearsal I thought, not only of her, but of all the things the pandemic has taken away. Now, at least in my neck of the woods, we’ve now gotten some of those things back. Our churches are open; I dine at restaurants; there is live theater again. The great Years of Zoom even brought me back in contact with people and groups I’d lost touch with, and built a few new groups out of the ashes. But we’ve lost people. COVID killed some; others were transformed beyond recognition by mental-health crises. Folks got fired. Restaurants and businesses that had been community institutions closed. Relationships crumbled. Anger and trauma are rampant. And darn it, it’s a little thing, but I never got to be in “Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat.”

We were all deprived of the Way of Affirmation for over two years – the celebration of God and creation’s goodness through community and art and theater and feasting – and the implications are going to be generational. We may yet get to something beautiful where we’re going, and Jesus may yet use all this, but we don’t get back the same things we lost, not even out of his fullness. He seems to be plumb out of oboes. And what was he doing taking them away in the first place, anyway?

Now’s the point where I should either announce my deconstruction (I’m Gen X, I’m too old and tired to deconstruct) or my transformation into an open theist. I will do neither; I will sit here, traumatized, and repeat the Nicene Creed.

I guess FINLANDIA is still a beautiful tune.

Image: Unsplash.