I was sitting in a downtown Thimphu coffee house, waiting for my companions. My neighbor was a Bhutanese national. We began to talk. Nearly everyone speaks English, it’s the official language of government and much of commerce.

My experience is that the first question from a Bhutanese to someone visiting is usually inquiring what one thinks of their country. Which I can easily respond to, by saying I love it. I have fallen in love with Bhutan.

Then, as usually happens with me should there be enough time, the conversation turned to Buddhism.

He asked I were a follower of the dharma. I replied yes, but not within the Vajrayana. About, which, I admitted I know shamefully little. I thought I was inviting him into a conversation about his version of our way. But, instead he pushed me and wanted to know my Buddhist background.

I said I was a Zen priest within a Japanese tradition. He wanted some clarification and asked if I were a monk? I said no, sliding over the fact that we traditionally do use monastic language to describe our ordination model. But we’re not celibate, not monastic in that commonly understood way. So, no was an answer to the meta question, was I a Vinaya monk? But not a lay person, either. Someone with some monastic training and cumulative many years of intensive training. The best word I’ve found for what I am is priest. A Zen priest, someone with long years of training, a commitment and vow, an obligation of transmitting the forms and style as best I can, and empowerments to do these things within a lineage.

He smiled broadly, and said, “Ah, you’re a Gomchen. A Zen Gomchen!”

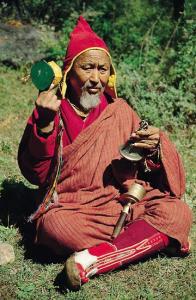

I was pretty sure I wasn’t being insulted. But just to be sure I asked what that meant. He replied how gomchen meant “great meditator.” He explained in addition to nuns and monks, Vinaya ordained clergy, in Bhutan the gomchen are very important in the community religious life. They’re not ordained. But they are trained, have received empowerments, can perform the critical rituals, and are spiritual leaders. But also they can and frequently do marry. Usually they live in the village and have an ordinary trade to support themselves.

He repeated, you are a Zen gomchen. And he put his hands together and bowed to me. I had the feeling if we weren’t in a coffee shop he would have done a full prostration.

Soon he left and my companions arrived.

Reflecting on it, while I bristled a bit at the “not ordained” part. Part of my path is absolutely about ordination, if not Vinaya monasticism. And, I could see how it actually wasn’t a bad way of understanding who and what I am – certainly for someone immersed in Bhutanese Buddhism, but not particularly clear on the forms elsewhere in the Buddhist world. And, noting the. Japanese-derived has no clear analog anywhere. (Okay, excepting the Korean Taego Order, which is probably the closest to us in world Buddhism without being us.)

I know I do that kind of interpreting from what I know all the time. It’s one of our human super powers, if also on the dangerous side when we cling to it too much. Sort of like, well, everything…

Later I looked it up and found a couple of interesting explanations of the Gomchen. For instance. Also this. And this.