For previous posts in this series, see CST 101, 102, 103, 104, and 105A.

Capitalism also ignores the effects of scale in its neat little picture of enlightened self-interest. Even if your enterprise start from the bottom—which is rare, but we’ll get to that later—once you’re big enough, your production costs go down, which allows you to undercut smaller businesses by selling the same product (or a better one, or a worse one) for less. Do this enough and competitors go out of business or get bought out, not because of anything wrong with their products but because they can’t keep up with your business model—a business model you can afford only because you already have more money than they do. That may not sound terrible, but its effect is to stymie the competition that capitalism claims it values as a way of keeping quality high. The natural tendency of capitalism over time, unless directly interfered with—which is the thing capitalists keep saying is an affront against common sense and God and the existence of puppies—is to amass money and power in the hands of a few, who are thus rendered, effectively, not responsible to anyone.

But the encyclicals of the last hundred and thirty years or so, the ones which have explicitly confronted capitalism (and other things, yes) in the context of Catholic teaching, identify two problems with capitalism, two problems that are inextricably bound together: the problem of promoting the common good, and the problem of exploitation [human beings have rights and dignity that rise above being treated as things, which capitalism always does to workers].

First, the common good. Human beings are sinful, as we know, but human beings are nonetheless made for communion with God and with each other. Selfishness is real, but selfishness is not the only human impulse, nor the final defining factor in human behavior. The responsibility of both the Church and secular society, in differing ways, is to promote the common good—the shared interests of every person in society—something which can only be attained through cooperation and good will. But capitalism takes as foundational that the state has no business promoting the common good (in direct contradiction to the Church’s teaching on the subject) and that selfishness is the only reliable motivator. That’s a much darker and more toxic idea of humanity than the doctrine of original sin; but when you tell people that they are selfish and nothing else, they will tend to behave that way. And it is in the nature of selfishness to be destructive, not beneficial, because we were created to cooperate; and the corruption caused by selfishness builds on itself, it gets worse over time, it saps virtue and energy and intelligence—put another way, enlightened self-interest does not remain enlightened for long. You can’t build a healthy, happy society by telling it to not just allow for but actively rely on evil. It’s metaphysical nonsense.

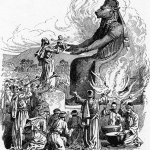

And secondly, exploitation. I don’t know whether private property as defined by Marxists (i.e., an individual owning the means of production for a mass of others, who are therefore beholden to him for their work and well-being) is intrinsically unjust; the Church has not said as much, and I don’t yet understand the theory of value well enough to have an opinion of my own. But it is definitely true in practice that the owners of capital—i.e., the means of production, so things like factories and corporations—have been exploiting workers since the Industrial Revolution, and continue to do so. Jeff Bezos isn’t worth $150 billion because he did $150 billion worth of work; no billionaire is, because it is not actually possible to earn a billion dollars. He’s worth $150 billion because his employees generated all that value and, rather than apportioning their compensation either equally to everyone or in accord with their actual needs, he paid them a wage and kept all the rest of the profits that their work generated for himself.

For the defenders of capitalism working on a thousand-word reply on how the Catholic Church only rejects this because she has been infiltrated by commies, (1) no, and (2) it’s not clear from the Church’s encyclicals that she insists profits must be divided equally or equitably: what she insists on is that every person is entitled to a just wage (something Scripture is also eloquent about), and she includes things like “the ability to support yourself and your family” under the heading of justice. Capitalist claims notwithstanding, consent alone has never been the sole determinant of whether an economic transaction is just. A person can consent to be harmed, e.g. through slavery or prostitution; and a person with enough power can so arrange society that the poor are not merely disadvantaged, but have no real choice save to accept the exploitation of the capitalist in order to survive. These are precisely the “sins that cry out to heaven for vengeance” in the Catholic moral tradition, and to defend them is to defend sin and error, whether it calls itself economic liberty or not.