THIS SERIES DEALS WITH SEXUAL ABUSE. PLEASE READ WITH CAUTION.

AN INTRODUCTION AND FURTHER DISCLAIMERS

MAY BE FOUND HERE.

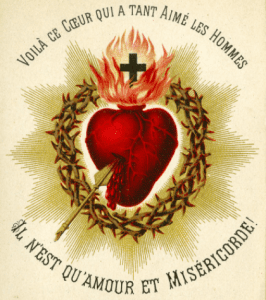

Almighty God, who wouldst not that the sinner should perish, and warnest the wicked of his destruction, that he might turn and be saved: Forgive us, we pray, for our transgressions, and confirm us in a spirit of righteousness and penance; through Christ our Lord, who liveth and reigneth with thee and the Holy Ghost, ever one God, world without end. Amen.

Previous post in this series: The Victims

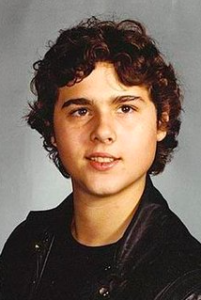

Theodore Edgar McCarrick

Cardinal McCarrick in Switzerland in 2008 (source).

Theodore McCarrick was born in New York in 1930. His father died when he was three, and he was raised principally by his aunt and grandmother. He habitually referred to his cousins as his brothers and sisters, and to their children as his nieces and nephews. He later extended this habit to the children of families he was close with. McCarrick often referred to his victims, regardless of age, as his “nephews.”

Throughout his career, McCarrick participated in a large number of episcopal committees and ministries. He traveled all over the world, including several places (e.g. Israel, China, and Bosnia) that many clergy were fearful to visit. He also famously declined his salary as a bishop and his pension after retiring in 2006.

As a cardinal, McCarrick was a leading figure in drafting the USCCB’s Dallas Charter in 2002. This laid out reporting guidelines for claims of abuse, and set out disciplinary practices, including an ostensible zero-tolerance policy for priests found guilty of abuse. Conspicuously, the idea that a bishop might be an abuser barely appears in the Charter. If someone does accuse a bishop, responsibility lies with the accused to inform the Nuncio; the power to discipline bishops is reserved to the Pope. It’s hard not to see the hand of McCarrick in that, but I can’t prove it.1

Sex, Lies, and Sacrilege

Most of the incidents in the report took place while he was Bishop of Metuchen and then Archbishop of Newark. He had bought a sizable house on the Jersey shore. His commonest tactic was to invite a group of seminarians or priests there for a weekend retreat. McCarrick said that, as a bishop, he should get to know his priests and their lives. There would be just one more person than there were beds, due to “miscounting.” He would select one young man to share his bed, since it was larger than the others, while the rest would sleep singly. (McCarrick later explained that he shared his bed because it would be unseemly for two seminarians to share a bed, but, since he was a bishop, “nothing was going to happen.”)

What followed differs dramatically, case by case. Some victims spoke of little more than uncomfortable back rubs and immodest dress. Others witnessed penetrative sex while one or more additional people were in the room. Most lay somewhere between these extremes.

McCarrick also frequently committed sacrilege. He apparently absolved his accomplices,2 and had them absolve him—which Canon 977 forbids, and in fact invalidates. He said Mass and partook of the Eucharist with unabsolved sins. The report mentions that the CDF found McCarrick guilty of soliciting penitents in the confessional, though I didn’t notice any details. He may have blasphemed the sacrament of Confession, by using it euphemistically to refer to sex (though this isn’t clear). And finally, he perjured himself to the Pope by swearing on his oath as a bishop that he was a virgin.

Why?

It’s easy to give simple explanations for predatory behavior. A strong sexual appetite might drive someone to break rules. A swollen ego might enjoy exerting power over others through sex. A genuinely sadistic person might just like inflicting damage and pain on people, especially in such an intimate, lasting way.

For my money, I doubt McCarrick is a sadist. I met the man once—in fact, I served Mass for him when I was in college. He had a reputation for being not only charismatic, but sweet and morally upright, and that was certainly how he came across. That sort of persona can be an act, sure; but keeping up an act is exhausting, and people who enjoy hurting or dominating others in secret tend to find socially acceptable ways of doing it in public too. Cutting remarks, “jokes,” unnecessary strictness, that kind of thing. And it’s especially easy to pull those things off when you hold a position like his. But, judging from what facts I know, McCarrick wasn’t like that.

It might seem impossible to do such heinous thing without being pure evil. But that’s because we’re used to cartoon morality; evil is never pure. Besides, rationalizing and compartmentalizing are extremely normal behaviors. I suspect something quite different was driving him.

One thing stood out to me in the report. Back when his superiors were considering making him a bishop, several people said he was ambitious. A small, rather harmless flaw? A lot of people would say so; several did at the time.

But I think ambition, of a particular kind, is the key to the man. He didn’t just want prestige. He wanted to accomplish things—and be appreciated for it. We tend to think of vanity as a craving for adulation without substance. But there’s a kind of vanity which isn’t satisfied with that, one which needs real achievements to be vain about. The reason it’s still vanity is that it’s still in service of self-image; it just serves self-image differently. (“Beata Maria, you know I am a righteous man; of my virtue I am justly proud …”)

The desire to achieve is clear from his tireless, unbelievable schedule. “Long hours” doesn’t begin to describe it. Secretaries and assistants describe a man who was up at five and didn’t stop until midnight. The word travel appears over two hundred times in the 449 page report, and his itineraries boxed the compass. His domestic work was equally incessant. He celebrated liturgies both regular and special (he had a particular fondness for officiating at the weddings and baptizing the children of his “nieces and nephews”). He led or participated in a host of charitable projects and USCCB assignments. And before and after coming to Washington, McCarrick was a political contact and mediator, working to advance causes like immigration reform and religious freedom.

It’s Not My Fault

What does this have to do with the sexual abuse? I suspect it’s how he excused it to himself. Not with anything so crass as: I do so much good, I’ve earned a little evil. That would give the game away. Something more like: I deserve to unwind a little, followed by “reaching out” to someone he expected to “appreciate” him. It would probably get more and more conscious over time, as the excuse began to do its work more and more automatically. I cannot prove this, of course. But I found several things he said significant. One comes from the testimony of Priest 1, recounting one of multiple instances in which McCarrick molested him:

Then he started to tell me what a nice young man I was and what a good priest I would make some day. He also told me about the hard work and stress he was facing in his new role as Archbishop of Newark. He told me how everyone knows him and how powerful he was. The Archbishop kept saying “Pray for your poor uncle.”

I don’t think McCarrick was, in his own mind, lying. I have a hunch that the references to the burdens of power were a play for sympathy rather than intimidation. Or rather, it was probably both, but sympathy was what he wanted. Frightened compliance was merely what he would settle for. He may well remain oblivious to his own hypocrisy.

The impression I get of McCarrick is not that of a man who took pleasure in harming others—though he was willing to. It’s of a man so hungry for appreciation, he wore himself out doing genuinely important, admirable things, and when the reward for that wasn’t enough, he decided to reach out and take something that did make him feel appreciated. There’s nothing like sex to make you feel wanted. Or to make you rationalize what it takes to get it. Maybe the workload itself appealed to him as an excuse for the sex, too: a way to ensure he was under enough stress to justify acting out.

And Have Not Charity

There are a few other remarks that suggest a wounded feeling of under-appreciation. Shortly after his retirement, Cardinal Re asked McCarrick to limit his travels and media visibility, because of rumors about him. Not that Re believed the rumors—we’ll get to that. But the Vatican did not want to invite gossip.

McCarrick evaded and resisted this advice; that much is obvious from his ongoing foreign travel and public ministry. But he wrote deferential letters professing total readiness to comply. At least, he attempted deference. The mask slipped here and there. In one, he wrote: “I pray that I will always be willing to accept the will of my superiors as the will of God”—a commonplace for those under a vow of obedience, except that he added: “whether it seems just or unjust.” As if limiting his worldwide travel were an injustice. In another letter, ostensibly clearing his schedule with Cardinal Re, he mentions three commitments with the remark “I presume that I have permission to continue to try to be of help in these matters.” Another letter opens one paragraph with the words “I am presuming that I may continue to serve the Lord and the Church in a way that will not involve public appearances …”

But the most arresting letter dates to 2009. It reads in part:

Up until this time, I have refused four honorary degrees that were offered to me … I have had a number of requests from the incoming United States government [the Obama administration] to be involved in public events. … I have therefore turned down requests by the Office of the President-elect to be present at certain prayer functions and to have a role in the National Prayer Service. The disappointment … was highlighted by a personal phone call from the Vice President-elect, Senator Joseph Biden. I believe that I took care of this without losing a friend for the Church or for myself, but it is very difficult. (Dear Eminence, it is so interesting that my reputation among so many of my brother Bishops and among the leaders of government, who have access to investigative agencies, still remains so high that they want me present at their functions while the Church seems unwilling to have any confidence in me.)

The weird blend of plaintiveness and venom jumps off the page. And it’s all about his image and importance—not so much as somebody powerful, but as somebody who serves, helps, mediates, makes people smile. It’s an image a lot of us would like to cultivate, myself included. It is a subtle snare. Yet the Apostles knew it well: Though I bestow all my goods to feed the poor, and though I give my body to be burned, and have not charity, it profiteth me nothing.

This, incidentally, is why I fiercely hate the saying “The point of life is to be a saint.” A saint is someone who loves God above all else, so the saying is technically correct. But what it suggests to the imagination and emotions is “be someone Catholics will admire.” And that little shift, from God to the good opinion of other Catholics, is a splendid road to hell.

The Mirror

Some people might read all this talk about sympathetic motives as lessening his crimes. I don’t. Preying on people sexually doesn’t become less heinous by having a motive most of us can understand. It becomes scarier.

I have little more than educated guesses. I discuss my guesses here not to trample on his reputation, but because what is possible to one man is possible to others. Most of us don’t like to think about that. We like to think of abusers as a different species; it’s comforting to call them monsters. Monsters aren’t human. I’m human. I’m not like that. I could never be like that. My indulgences are no big deal.

But if McCarrick is not a monster, but a human being,—?

Some have paid me an undeserved compliment by supposing that [The Screwtape Letters] were the ripe fruit of many years’ study in moral and ascetic theology. They forget that there is an equally reliable, though less creditable, way of learning how temptation works. “My heart”—I need no other’s—”showeth me the wickedness of the ungodly.”

—C. S. Lewis

Further posts in this series: The Bishops’ Gambit; Pope John Paul II; Pope Benedict XVI; Pope Francis; The Venom of Viganò; Den of Thieves; Quo Vadis

1To be clear, bishops being unable to discipline each other wasn’t new. All bishops are in some sense equal; only the Pope is unequivocally above them. Allowing bishops’ conferences to discipline their members would be a radical change in canon law. But (as far as I know) the USCCB was free to request a change like that from the Vatican. Or they could have asked for the Nuncio to receive authority to discipline them, since the Nuncio is already the Pope’s representative at the national level.

2I say accomplices here advisedly. McCarrick reportedly had consensual sex, as well as engaging in predation—although of course it’s hard to say how consensual any sex with a powerful superior can be. As far as I can tell, and judging just from the report, the people I’m describing as accomplices participated willingly. These do not include Priest 1 through 8, who were clearly victims; I’m also, for the moment, working on the assumption that the report itself is reasonably complete and accurate, a question we’ll be coming back to.