AHAB (All Homilies Are Bad)

As many of my readers know, I’m a convert to Catholicism. (It’ll be thirteen years as of March 22nd.) And if there is anything not to convert for, it’s preaching. Most Catholic homilies are bad—that’s just kinda the way it is.

Well, maybe bad is too simple a word. They aren’t usually heretical in my experience, and while their advice usually isn’t all that helpful, I don’t often hear downright toxic stuff from the pulpit either. Homilies do tend to be dull: not because their subject matter is boring in itself, but, I think, just because not very many people have all the gifts of Scriptural and theological knowledge, writing, and public speaking that make a homily interesting. (Personally I rather wish we’d revive the tradition of reading old homilies written by great saints, like Chrysostom, Augustine, or Newman.)

All this doesn’t matter for Catholics the way it would matter to an evangelical. Catholic liturgies are primarily about the Blessed Sacrament, not the homily. But people do listen to homilies, and they certainly complain about homilies. Herein, I propose to complain both about homilies and about complaints about homilies, because having a sense of irony is for suckers.

Bless Me, Father, But I Have a Few Notes

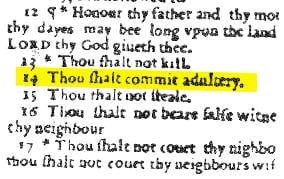

The topic’s on my mind because of something tweeted by a Franciscan friar on Twitter: “When people want me to preach more about sin it is always about someone else’s rather than their own.” Another priest quote-tweeted him, adding, “In twenty-two years as a priest, I’ve never had a straight person tell me how important it is that I preach against adultery but a lot of them have told me how I need to preach against homosexuality.”

Obviously, several people in this priest’s replies took this as an invitation to tell him what they’d like to hear in a homily, or to straight-up tell him what he should be preaching on. (Best of all was the person who, instead of “adultery,” accidentally typed “sultry.”)

A printer’s error in this Bible from 1631 led to the edition in question being branded “the Wicked Bible.”

But what stood out about a lot of them was their focus on what “the World” needs to hear. Some emphasis firmness about dogma; others emphasize patience and mercy. But most are about preaching to—or at—outsiders and bad Catholics. Who decides who’s a bad Catholic? We do. Or some favorite pundit; it makes very little difference whether it’s Dr. Taylor Marshall or Fr. James Martin, so long as they give us a way to put the people whose sins we find unsympathetic in the Bad category, and ourselves comfortably among the Good. Whether the Bad are the queers or the Communists or the Muslims or the trads or the capitalists makes very little difference. The point is that we are not them. We are the choir.

Burn the Choir

If there’s anything I despise, it’s preaching to the choir, because it is a complete waste of time. The March for Life is a perfect example. We already know we’re pro-life.1 We don’t need to stand around congratulating ourselves about it for two hours before we march (especially not in the wretched weather of a DC January). I’ve been to antiracist demonstrations and marches, and they’re a great deal more businesslike. We do it because most Catholics, whether at a march or from the pulpit, want to hear something familiar and comforting, not because it serves any purpose.

It’s not wrong to want comfort, of course. But when we only hear things that reaffirm the ways we’re in the right, I think we risk dulling a lot of our capacity for self-examination, repentance, and humility.

And here’s the thing—comfort is a very elastic quality. Intellectual types like me are apt to look down on people who want fluffy homilies, but ninety-nine times in a hundred, we’re looking for comfort as much as anybody else; we just happen to have eccentric tastes. A person whose faith is lukewarm may find a bland “God is nice” homily comforting. But to a person who’s fixated on guilt and punishment—their own or other people’s—a fire-and-brimstone homily may be extremely comforting. It reassures them that their feelings are right and proper, instead of challenging them and introducing doubt that would upset their (perhaps unacknowledged) emotions even further.

The Part Where I Tell Priests What to Preach

That’s kind of the hard part, though. What you want to hear may, or may not, have anything to do with what you in fact need to hear. And both of those things are quite unrelated to whether the homily is sweet or stern, intellectually or emotionally driven, long or short.

I’ve attended a parish where every homily, literally for years, was about the culture war, and most addressed Catholic doctrine (correctly, if pretty lopsidedly). I don’t know whether anyone at that parish got anything out of those homilies. The congregants were already conservative, educated, practicing, catechized Catholics. None of them had the slightest need for what was being given. They may perhaps have needed sermons on humility, or Church teaching on economics, or the fruits of the Spirit; too bad. Conversely, a parish that was sluggish and poorly instructed might have gotten a lot out of those homilies—which is not the same thing as saying they would have liked them. A good homily should probably be a little difficult, a little uncomfortable; not necessarily throughout, but here and there.2 It should prompt us to attend more deeply to God, and God is not something we can ever fully digest.

The point is, these people should be listening to me.

1For a certain value of “pro-life,” anyway.

2Not that I buy into the “A good homily will always make somebody mad” trope, either. That too easily turns into “Making people mad is a virtue,” a poisonous falsehood if ever there was one. I suspect a good homily will probably always risk making somebody mad, but that’s different.