Trinitytide

This is the longest single season in the Anglican Use liturgical year.1 In terms of the lectionary, it corresponds to most of Ordinary Time in the Novus Ordo calendar, but Trinitytide doesn’t kick in until after Pentecost—the chunk of Ordinary Time between Christmas and Lent equates with Epiphanytide in the Ordinariate’s calendar.

I got into this a little bit early this year in my series on sacred time; I there identified Trinitytide as one of the five principal seasons of the Catholic ritual year. There is a logic to such a large share of the year being devoted to Trinitytide (something I used to find disappointingly monotonous). Where the Christmas and Paschal seasons recount specific temporal events, Trinitytide implicitly opens upon eternity; and insofar as grace is the infused life of the Trinity—that idea of divine life being why green2 is the liturgical color of the season—the other two great mysteries of the faith, the Incarnation and the Redemption, are significant to mankind first of all because they communicate Trinitarian life to us.

Adoración del Nombre de Díos [Adoration of

the Name of God] (1772), by Francisco José

de Goya y Lucientes.

The Gospel passage for Trinity Sunday in Year C—which is comparatively short; I have only two notes on the text!—comes from John instead of Luke: specifically, from part of the Upper Room Discourse, or John 13:31-17:26. This discourse (which may be amalgamated from multiple “talks” given by Jesus to the disciples, possibly even including things said to them after the Resurrection) is the promulgation of the New Covenant, and therefore the setting in which he delivers the new law per se: “As I have loved you, that ye also love one another,” as he says in 13:34. This passage comes from much later in the discourse, where he is explaining the role the Holy Ghost is going to play in the life of the Church.

John 16:12-15, RSV-CE

I have yet many things to say to you, but you cannot bear them now. When the Spirit of trutha comes, he will guide you into all the truth; for he will not speak on his own authority, but whatever he hears he will speak, and he will declare to you the things that are to come. He will glorify me, for he will take what is mine and declare it to you. All that the Father has is mine; therefore I said that he will take what is mine and declare it to you.b

John 16:12-15, my translation

Many things I have to speak to you about, but you cannot bear them at present; when he comes, the Spirit of truth,a he will guide you into all the truth, for he will not talk on his own, but whatever he hears, he will tell you, and he will announce the things that are coming. He will glorify me, because he will take what is mine and announce it to you. Everything which the Father has is mine; because of this, I said that he takes from what is mine and announces it to you.b

Cathedra Petri [“Throne of Peter”] (1666),

by Gian Lorenzo Bernini. Photo by Wikimedia

contributor Dnalor 01, used under

a CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

Textual Notes

a. the Spirit of truth (τὸ πνεῦμα τῆς ἀληθείας [to pneuma tēs alētheias]): Unlike my divergence from the RSV articulated in note h of this post, here, there is no contextual ambiguity about whether “a holy spirit” or “the Holy Spirit” is meant: A good deal of this whole discourse is about the Holy Ghost, or the Paraclete. This title is derived from the Greek παράκλητος [paraklētos]; its literal meaning is “one called alongside, helper, aide,” from which it got two further senses. One was “advocate, legal assistant”—and note the contrast here with the etymological ancestor of the word devil, namely διάβολος [diabolos] “accuser, slanderer”; the pair is not quite, but draws close to, that of a plaintiff versus the counsel for the defense. The other was “mediator, intercessor,” which we see St. Paul pick up in Romans 8.

b. All that the Father has is mine; therefore I said that he will take what is mine and declare it to you | Everything which the Father has is mine; because of this, I said that he takes from what is mine and announces it to you (πάντα ὅσα ἔχει ὁ πατὴρ ἐμά ἐστιν· διὰ τοῦτο εἶπον ὅτι ἐκ τοῦ ἐμοῦ λαμβάνει καὶ ἀναγγελεῖ ὑμῖν [panta hosa echei ho patēr ema estin: dia touto eipon hoti ek tou emou lambanei kai anangelei hümin]): All of this pertains to the temporal mission of the Holy Ghost, i.e. his activity in the Church on earth. This should not be confused with the distinct question of the procession of the Holy Ghost—that is, whether, ontologically, he proceeds from the Father and not the Son, or from the Father and from the Son (or, as a pseudo-third possibility, whether this is not something we can know).

If you’ve heard the notorious Latin word filioque, “and from the Son,” this debate is why it is important. In the Latin West, starting in Spain, filioque was added to the Nicene Creed as a way of combatting semi-Arianism. (Arian Christianity was prevalent among the Visigoths and Ostrogoths, who governed Spain and Italy respectively from about the late fifth century, and Catholicism made slow headway among them up until about the eighth.) The East objected to this addition, partly on procedural grounds—it was argued, and with good reason, that the Creed should not be changed except with the consent of an ecumenical council—and partly because, though not all did so, many Greek and Syriac-speaking theologians disagreed with the doctrine it represented.

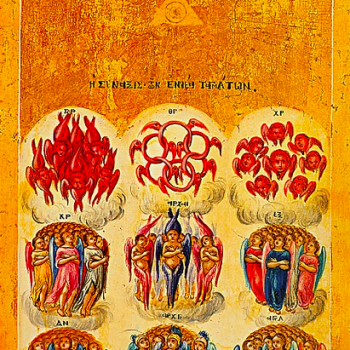

The Trinity (either 1411 or 1427),

written by Andrei Rublev.

I am not an expert on Trinitarian theology, so take what follows with a grain of salt. Moreover, since I grew up Protestant and then became a Catholic, it is predictable that I should side with the filioquists3; I have only ever partaken of Latinate Christianity, whether in or out of communion with Peter. However, I thought for a long time about converting to Orthodoxy rather than Catholicism, and the topic of the filioque—both ritually and doctrinally—was not absent from my deliberations. Foreseeable my loyalty may be, but it is not thoughtless.

And the thought that mainly occurs to me in support of the filioque is: How is God the Son supposed to be “the image of the invisible God,” “the brightness of his glory, and the express image of his person,” so “that in all things he might have the preeminence,” and how can it have “pleased the Father that in him should all fulness dwell,” if the Spirit does not proceed from the Son? Wouldn’t that render him “the all-but-image of the invisible God,” “part of the brightness of his glory, and the incomplete image of his person,” so “that in the overwhelmingly majority of things he might have the preeminence”?

I’m skeptical of most of the theological conclusions extrapolated from the filioque, whether the extrapolating is done by the doctrine’s opponents or its advocates. In part, this is because I’m resistant to the idea that we can or should hold forth freely about the “mechanics” of the Trinity, who is the supreme mystery of all existence!

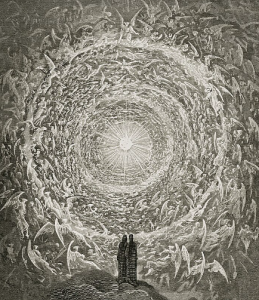

“The Empyrean” (1892), an illustration of

Canto XXXI of the Paradiso, drawn

by Gustave Doré.

But I’d also point to the very verse that gave rise to this doctrinal note, which was originally about the temporal mission of the Holy Ghost: “He takes from what is mine and announces it to you.” Arguing about theological niceties, while it is not pointless, does have a strong tendency to distract from this; all too often, arguments about theological niceties are the smart person’s way of explaining to ourselves why God hathn’t really said we must not eat of the tree that is in the center of the garden …

Footnotes

1The liturgical year of the Roman Rite (regardless of use), because it always begins on the First Sunday of Advent and always ends on the Saturday after Christ the King, contains a range of days slightly wider than that of the natural year—if I’ve mathed right, it’s 358 days at minimum and 373 days at maximum.

2If I were doing a Percy Dearmer, I would doubtless take this opportunity to mention that, due to the tree’s importance in Scripture, olive green is the most ideal shade of green for liturgical use, in much the same way that wine-color is the most preferable shade of purple. But I am not doing a Percy Dearmer, so I shall say nothing about the subject.

3That is, I am a filioquist in theology. I am at the same time firmly of the opinion that—though there are certain extenuating factors that probably apply—the (fairly late) decision of the papacy to insert the filioque into the public recitation of the Creed, without first securing the assent of the Church in ecumenical council, was a grave breach of the heavenly courtesy with which the Church ought at all times to comport herself. By the same token, I don’t consider it my place as a layman to desist from reciting the Creed at Mass as it was taught to me, including the filioque, but I would consider its removal from the liturgy a deeply appropriate gesture on Rome’s part. (Since I am therefore kind of caught between two impulses, when saying the Creed at Mass, I pray a short, silent prayer for Christian reunion when we say “and from the Son.”)