Blessed Are the Middle Class in Spirit

Ah, poverty—everyone’s favorite Christian value. It all but outstrips the glamor of patience, the old crowd-pleaser forgiveness, and the ultimate in sexiness, death to self.

St. Luke, probably thanks to his concern for the marginalized (see my two-part introduction to Luke, especially the latter half, for details on that), highlights Jesus’ teaching on poverty more persistently than any other canonical Gospel. If “teaching” is the right word, that is; “insistence” might be better, since he doesn’t give a lot of information in the indicative—he tends to prefer imperatives. Embarrassing ones, like “Give away all of your belongings.” Most churches nowadays don’t ask that sort of thing of their members. That’s … kind of odd, isn’t it? That something Jesus told so many people, often as a precondition of following him at all, is just gone from the way we talk about the faith today?

Famine from the Angers Apocalypse Tapestry

(1382); he carries scales, symbolizing food

becoming disastrously costly. Photo by Remi

Jouan, used via CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

This might seem like the kind of thing only Mennonites would take an interest in—unless you really took the wrong lesson away from reading The Name of the Rose and ultimately converted to Catholicism about it, but come on, that would be lunatic behavior, and I digress. Since poverty plays a prominent and arguably unique role in the Third Gospel, let’s start by getting our concept of poverty a little clearer.

God’s Sheep at the Caprine1 Café

I forget where he says it exactly—What’s Wrong With the World, I think—but there’s a passage in one of G. K. Chesterton’s essays where he pitches this definition: “A poor man is a man who has not got much money.” The reason he then gives for doing this is to accent the common humanity of the poor, the secure, and the wealthy, in a period when, he felt, sociologists and economists were talking about the poor almost as if they were a different species. The reminder is a valuable one. I don’t know how true this is about the poor in general; but it seems clear to me that many people in this country view the homeless exactly as a different species. The casualness of so many people’s cruelty to them, and the reaction to this cruelty on the part of so many Christians, ranging as it typically does from “nothing” to “rationalized, unhesitating participation,” make my blood run cold. Biblically, such cruelty really is given the name sodomy, and the warning of divine wrath that name carries with it.

A small homeless encampment in San Francisco

in 2020. Photo by Christopher Michel, used under

a CC BY 2.0 license (source). Take thirty seconds

and just imagine trying to sleep here.

As a theological term, poverty can have a few meanings. There’s the “poverty of spirit” mentioned in the Beatitudes (only in Matthew, though—Luke recounts a more literal version): that phrase is usually interpreted to mean humility, or a vivid sense of continuous dependence upon God. Or it can mean the virtue of which poverty is the most convenient symbol, namely the virtue of detachment from temporal goods.

Alternatively, it can mean religious poverty: in other words, the formal renunciation of one’s right to personal property. This is a normal element of the monastic life,2 and in many orders goes with a reliance on collective property instead—mine is forsaken for ours, so to speak. (Benedictine spirituality tends to involve this—that’s why you get things like beers, liqueurs, cheeses, wines, or coffee being made by monks in such-and-such an abbey.) This is, or professes to be, an instantiation of primitive Christian custom:

And when they had prayed, the place was shaken where they were assembled together; and they were all filled with the Holy Ghost, and they spake the word of God with boldness. And the multitude of them that believed were of one heart and of one soul: neither said any of them that ought of the things which he possessed was his own; but they had all things common. … Neither was there any among them that lacked: for as many as were possessors of lands or houses sold them, and brought the prices of the things that were sold, and laid them down at the apostles’ feet: and distribution was made unto every man according as he had need.

—Acts 4:31-35

Render Unto God

An illumination from the Queen Mary Psalter

(early 14th c.) depicting a reeve (“manager” is

probably our nearest equivalent) directing

serfs (unfree peasant laborers at a manor).

Now, the Church states plainly that the poverty observed by consecrated religious brotherhoods, like the obedience and celibacy to which they also commit themselves, is not a basic moral requirement. Those renunciations, known as the evangelical counsels,3 are works of what used to be called supererogation, a “going beyond the call of duty.” (Though applied to something quite different, I think a maxim of Anglican spirituality is a very good way of thinking about works of supererogation: “All may; some should; none must.”) However, and a little uncomfortably, it must be admitted that this is not the impression Christ gives us in our text for today. “Whosoever he be of you that forsaketh not all that he hath, he cannot be my disciple” sounds pretty categorical.

The Church either never interpreted this as an absolute requirement, or she relaxed the requirement in the very first years of her existence. We know this, because in Acts 5, almost immediately after the quotation above, we get the frightening story of Ananias and Sapphira. And in that story, although we’ve just been told there was a laudable habit of selling one’s property and giving the money to the apostles, all the same, St. Peter goes out of his way to point out that the property the couple sold was their own, to keep or sell as they pleased; and after the sale, the money was likewise their own, to keep in whole or in part if they so chose. If renouncing all property had ever been classed as a moral requirement for Christians, it wasn’t any more by the time of Ananias and Sapphira, and their tale comes even before the diaconate was instituted—this would have had to take place in the first two or three years of the Church’s existence.

I think the interpretation that this just never was a moral rule makes more sense. My hunch is that this text from Luke about “being my disciple” is actually talking about a specialized vocation, the one which the apostles had. (Of course, modern bishops also don’t generally practice apostolic poverty, though it might be a very good thing if they did. But that probably merits a post unto itself.) There were plenty of “Jesus movement” sympathizers who didn’t renounce their property, and on whom Jesus and the Twelve actively relied: St. Martha, for instance, or the Magdalene.

Medieval military towers in the Russian

Caucasus. Photo by Vyacheslav Argenberg,

used under a CC BY 4.0 license (source).

Yet the necessities laid on the apostles, while sometimes much more rigorous than those which ordinary believers need to observe, have a tendency to act as symbols of more universal duties. Not everyone is called to celibacy; everyone is called to chastity. Not everyone is called to sworn obedience; no one is exempt from obedience to God. Likewise here. Probably only a minority of people have vocations that involve renouncing property in general; even so, no matter what our vocation is, all of us need to cultivate that degree of detachment from our possessions which would allow us, if God asked us to do such a thing, to lose any or all of them forever. We’re certainly going to some day, in any case.

Luke 14:25-33, RSV-CE

Now great multitudes accompanied him; and he turned and said to them, “If any one comes to me and does not hatea his own father and mother and wife and children and brothers and sisters, yes, and even his own life,b he cannot be my disciple. Whoever does not bear his own crossc and come after me, cannot be my disciple. For which of you, desiring to build a tower, does not first sit down and count the cost, whether he has enough to complete it? Otherwise, when he has laid a foundation, and is not able to finish, all who see it begin to mockd him, saying, ‘This man began to build, and was not able to finish.’ Or what king, going to encounter another king in war, will not sit down first and take counsel whether he is able with ten thousand to meet him who comes against him with twenty thousand? And if not, while the other is yet a great way off, he sends an embassye and asks terms of peace. So therefore, whoever of you does not renouncef all that he hasg cannot be my disciple.”

Luke 14:25-33, my translation

Crowds of many people were going along with [Jesus], and turning, he said to them: “If anyone comes to me that does not hatea his own father and mother and wife and children and brothers and sisters, and even his own life,b he is not able to be my student. Whoever does not bear his own crossc and come behind me is not able to be my student. For if any of you wants to construct a tower, doesn’t he first sit down and calculate the price and whether he has [enough] to completion? lest that, with the foundation set, he then have no strength to finish up—all the onlookers will begin to belittled him, saying, ‘This man started to construct but did not have the strength to finish up.’ Or a king going out to meet a different king in battle, doesn’t he first sit down and take counsel whether he, with ten thousand [men], should encounter one coming to him with twenty thousand? And if not, even while that [other king] is far out, he sends a delegatione asking for peace. Likewise, then, every one of you who does not say goodbye tof all of his own belongingsg is not able to be my student.”

Textual Notes

Way to Calvary (ca. 1400), by Andrea di Bartolo.

Note the sword pointing at the Virgin’s heart,

and the tiny figures on the lower right, presum-

ably Alexander and Rufus with Simon of Cyrene.

a. hate | μισεῖ [misei]: If you grew up not only hearing sermons but paying attention to them, you have likely heard time and time again that this verb really means “to love less.” As you may have suspected, this is untrue: μισέω [miseō] is a primitive verb that means exactly what it seems to mean, i.e. “to hate.” (It’s sort of like that thing guys in parachurch ministries4 said all the time in the 2000s, that “in the Bible, ‘death’ means ‘separation’.” It doesn’t really, or at all, mean that. It means “death.” None of the pertinent languages are too coy to have a word for death and use it. Scripture is already profound, guys, it doesn’t need help.)

That said, there is some legitimate softening of the idiom that’s possible here. The notes in Joseph Thayer’s Greek-English Lexicon relate that “the Orientals,”—um, wow. Anyway—”in accordance with their greater excitability, are accustomed both to feel and to profess love and hate where we Occidentals, with our cooler temperament, feel and express nothing more than interest in, or disregard and indifference to a thing.” I used that “wow” way too early; so much more was in store in that sentence than I anticipated. Thank you, Thayer, very cool.5

So, if we take that quote and dial back the ambient racism by thirty degrees or so, it is true that hyperbole is, or was, a more typical feature of Semitic rhetoric than of most European styles. It’s perfectly tenable that in a verse like “Jacob I have loved, but Esau I have hated,” what the text means is simply that God has preferred Jacob to Esau in some sense. However, what is not so tenable is that this is what the text says; and that is well worth hanging onto.

Study for a portrait of the More family (ca.

1527) by Hans Holbein the Younger.

There is a scene in the justly-famous film A Man for All Seasons (if you aren’t familiar, it’s essentially a biopic of St. Thomas More), set shortly after King Henry VIII’s repudiation of his wife, Queen Katharine of Aragon, and formalization of the affair he had been carrying on with one of Katharine’s ladies-in-waiting, Anne Boleyn.6 More’s daughter, Meg, comes to him in great distress, saying that “They’re going to administer an oath, about the marriage.” More asks what the wording of the oath is, to which Meg protests that “We know what it’ll mean!” To this, the saint—a very honest man, and also a very shrewd one—replies: “An oath is made of words; it will mean what the words say.”

Now, St. Thomas More was a lawyer: obviously he knew that context, as well as literal wording, can influence meaning, and every dweeb from Plato to Wittgenstein has smugly pointed out that words are malleable. Yet they are not infinitely malleable. There are meanings that a given word, a given sentence, a given text, quite simply won’t sustain if asked to. Thus, despite being maddeningly difficult to pin down at times (and often containing more than one meaning on purpose—sometimes even with meanings the original author never could have meant to put there, if the Gospel of Matthew is to be credited7), the actual text of Scripture does limit what it can mean.

This principle ultimately lies at the root of my whole philosophy of translation. The reason I highlight flat-footedly literal renderings of words and phrases is not (just) because I am pedantic by birth and breeding. Insofar as it’s feasible, I want to afford the reader an equivalent range of possible meanings in my English version as that which exists in the original Greek. This would, admittedly, be an unattainable ideal, even if I were twenty times the Hellenist I actually am; still, I honestly think it’s probably more attainable than the ideal of convincing everyone in the world to learn Koiné.

b. his own life | τὴν ψυχὴν ἑαυτοῦ [tēn psüchēn heautou]: An alternate translation here would be “his own soul.” This receives a faint echo, maybe, in Romans 9:3.

Crucifix from Canterbury Cathedral. Photo by

Jonathan Cardy, made available under

a CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

c. bear his own cross | βαστάζει τὸν σταυρὸν ἑαυτοῦ [bastazei ton stauron heautou]: The word σταυρός [stauros] more strictly means “stake” rather than “cross,” or did so originally. I gather that, in Jesus’ time, it would still have been common to refer to the crossbeam by itself as a σταυρός, or a crūx simplex in Latin. (I touched on this subject in textual note d of this post last year.) It’s possible that it is such a crossbeam, rather than the whole contraption, that our Lord was forced to carry to Mount Golgotha. Natural trees were sometimes employed as the “uprights” of crosses, if they were:

i. close enough to the road for lots of people to see it;

ii. big enough (your average Japanese maple probably ain’t gonna cut it); and of course

iii. the right shape (a willow, for example, would be a terrible choice, with its generous canopy of concealing branches).

About that first one. Historically, the public notoriety of the death sentence has been a large part of the point of its use,8 so location accordingly mattered a lot. Funnily enough, this is why our habitual picture of Jesus carrying a prefabricated, complete cross may be roughly correct. See, whether or not you’ve got trees that fulfill conditions i., ii., and iii. in a given place is a bit of a crapshoot. In the Mediterranean, the odds get longer the further south you go. For a purpose like crucifixion, you want9 something single-trunked and sturdy, like an ash, oak, or beech; you’ll find those along roads in Umbria or Tuscany no problem. Jerusalem, as far as I can tell, isn’t especially well-stocked with such trees. It abounds in the gnarled forms of the olive and the fig, and in the extremely soft wood of the evergreen cypress, but my guess is that these will substitute about as well for the purpose as, say, swapping out the olive oil in a recipe for acorn flour. So, when Jesus was carrying his cross, it may really have looked like it does in the pictures. (This would also go some way to explaining why he needed help carrying his cross, since a complete cross would be more than twice as heavy; hence the impressment of St. Simon of Cyrene.)

Rock-cut tombs from the necropolis of Cyrene,

near Shahhat on the coast of modern Libya.

Photo by Joe Pyrek, used under

a CC BY-SA 2.0 license (source).

d. mock/belittle | ἐμπαίζειν [empaizein]: This verb is really quite funny. The element -παίζ- [-paiz-] is related to παῖς [pais], “boy” (in either the “child” sense or the “servant” sense), and the prefix ἐμ- [em-] is just a lightly-morphed version of ἐν [en], the preposition meaning “on” or “in,” while -ειν [-ein] is just an infinitive ending; so ἐμπαίζειν equates pretty closely to “infantilize.”

e. embassy/delegation | πρεσβείαν [presbeian]: This is a nominalized form of an adjective, πρέσβυς [presbüs], which means “old, aged.” This root also yielded πρεσβύτερος [presbüteros], “older,” or in its more archaic English form, “elder”; “senior” would also be a good translation in many contexts. Πρεσβύτερος is—rather ironically—the source of the two words priest and Presbyterian.10 In this context, “elders” come up because they were a common governing and/or diplomatic body in most places in the ancient world. It would certainly have been a delegation of elders who were in fact sent to sue to for peace in such a setting.

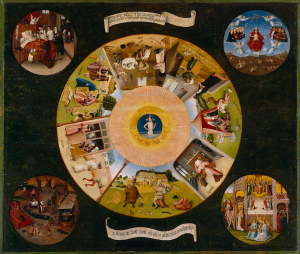

The Seven Deadly Sins and the Four Last Things

(1485), by Hieronymus Bosch.

f. renounce/say goodbye to | ἀποτάσσεται [apotassetai]: The root verb here, ἀποτάσσω [apotassō], means “to dismiss”; it thus came more generally to mean “bid farewell to, take leave of” in the middle voice. (Τάσσω is the ultimate root of the term “taxonomy,” or “setting things in order”; ἀπό is a prefixed preposition meaning “from, away.”)

g. that he has/his own belongings | τοῖς ἑαυτοῦ ὑπάρχουσιν [tois heautou hüparchousin]: I’m not sure why “all that he has” feels, to me, to pack less punch than “all of his own belongings”—maybe it’s just the extent to which “all one has” is a stock phrase. The verb ὑπάρχω [hüparchō] came up a couple of months back, in this post on a passage from Galatians 1, though I didn’t full get into its variety of meanings. Besides a specialized sense of “to be” (one nearly amounting to “to play a role”), it could also mean “to possess, have ready, have on hand.” The idea here, I think, is something like “personal effects,” exempting nothing at all from the reach of what may have to be surrendered.

Footnotes

1Caprine, believe it or not, is the adjective for things pertaining to goats (and ovine is the same for sheep)—it’s related to the term “Capricorn,” literally “goat’s-horn.”

2Normal, not universal: the nature and extent of this renunciation varies somewhat from society to society. Pallottines, for example, commit to “share their resources” rather than renouncing property per se, while on the other hand, Franciscan Primitives (unlike most branches of the Franciscan Order) observe their founder’s Rule in its original rigor, giving up not only personal but even collective ownership of all property.

3I caution the reader that “evangelical” here has nothing to do with modern Evangelicalism in the US. In the Medieval period, “evangelical” tended to be used in something of the same way we use the word “apostolic” in English today—it implied or claimed association with the lifestyle of the apostles, whose work was to evangelize.

4By which I mean “specifically Campus Crusade, which is the only one I was involved in and also was still called that back then” (I am an old).

5In fairness, this remark apparently comes not from Thayer himself, but from an underspecified “Fritzsche.” I assume this means Christian Friedrich Fritzsche, a nineteenth-century Lutheran theologian; however, it could easily mean either of his sons: the elder, Otto Fridolinus, followed his father’s line of work, and the younger, Franz Volkmar, became a philologist.

6Or possibly about his repudiated marriage to Katharine of Aragon (pray for the canonization).

7Basically every text claimed in Matthew as a fulfillment of prophecy, when read in the original context, has nothing to do with prophecy of anything, let alone the Messiah. A typical example occurs in Matthew 2:15, where the poetically-phrased historical reference from Hosea 11 is about the Exodus, and was by most accounts written centuries before any idea of a Messiah had become part of Judaic thought.

8This is not (as far as I’m aware) a reason as frequently put forward by modern proponents of capital punishment, though I don’t have an explanation for why that should be the case. But modern theories justifying the death penalty have really nothing to do with why our ancestors practiced it—if anything, capital punishment is a splendid example of the strong human tendency to do much the same things in roughly the same circumstances, even while coming up with reasons to do them that are so incompatible between one group and another, we’ll sentence each other to death about it.

9I mean, I guess I don’t know what you want. Why are you doing this

10The term presbyter is yet a third loan from πρεσβύτερος—for (I suspect) rather an odd reason. See, the English word “priest” is used to translate two quite distinct Greek words in the New Testament: its own ancestor, πρεσβύτερος; and also ἱερεύς [hiereus]. The difference is that the latter term typically refers to the Levitical priesthood in the New Testament, whereas πρεσβύτερος was not thus restricted. By contrast, members of the Sanhedrin did not need to be Levites, only πρεσβύτεροι [presbüteroi], elders, of the Judaic community—which would probably mean rabbis, of whatever tribe. Jesus’ method of ordaining the apostles seems more akin to the ancient ceremony for consecrating rabbis than the rites set down in the Torah for installing Levitical priests (a topic I expand on a little in this post in the section “The Air Apparent”); this, among other facts, certainly suggests that there is not only a useful but a theologically important difference between the Levitic priesthood of the Mosaic Covenant, and the Melchizadokite priesthood shared by Christ with New Covenant priesthood in the Church. In theory, this should make “presbyter” a useful term to have in our lexicon, but I can’t really tell if it’s catching on. (To me, something about it seems … eh, kind of try-hard? I don’t know why.)