Many of the traditions associated with the modern-day Easter speak to the ideas of rebirth and renewal. The trappings of Easter are also directly related to Spring and the natural rhythms of the Earth. Plastic grass is no substitute for the real thing but it’s still a welcome site after a long winter with very little greenery. Easter traditions unrelated to Jesus are not necessarily “pagan” in the sense that they all date back to the pre-Christian Era, but they might be pagan in the sense that they reflect the natural world. People have always felt drawn to the rhythms of the Earth regardless of what deity they worshipped, as a holiday Easter is a good example of this.

Much of the information here I’ve covered before and with a bit more depth (most specifically in a post entitled Eostre, Easter, Ostara, Eggs, and Bunnies), but I just see so much misinformation and bad history this time of year that I couldn’t help but revisit some of those ideas. Whatever Spring celebration shows up on your calendar I hope it’s joyous.

Easter was named after Isthar. This was all over social media last year and probably will be again. I am happy to say that this completely inaccurate (and perhaps dishonest) meme didn’t come from the Pagan Community in 2013, it come from an online Atheist group. Easter and Ishtar were never pronounced the same, and besides Ishtar is a Middle Eastern (Babylonian, Assyrian) goddess. The word Easter is used in Germanic languages (like English), and probably wasn’t used all that often until the Seventh Century. It’s first mentioned by the British writer Bede (673-735 CE). Early Christians (and a lot of modern ones) called the holiday Pascha, which can be linked to the Jewish Passover.

Easter was named after Isthar. This was all over social media last year and probably will be again. I am happy to say that this completely inaccurate (and perhaps dishonest) meme didn’t come from the Pagan Community in 2013, it come from an online Atheist group. Easter and Ishtar were never pronounced the same, and besides Ishtar is a Middle Eastern (Babylonian, Assyrian) goddess. The word Easter is used in Germanic languages (like English), and probably wasn’t used all that often until the Seventh Century. It’s first mentioned by the British writer Bede (673-735 CE). Early Christians (and a lot of modern ones) called the holiday Pascha, which can be linked to the Jewish Passover.

Ishtar was also not associated with rabbits and/or eggs. Like Jesus, she did slip into the underworld on at least one occasion, but she was also a goddess of sex and fertility, something Jesus certainly was not! She also has associations with war, also not a Jesus thing, though many of his followers seem to be fans. In short, Ishtar and Easter have nothing to do with each other than sharing a few letters.

The Easter Bunny is ancient pagan icon. The Easter Bunny is one of those things that most certainly feels pagan, and makes sense as a pagan custom, but it’s impossible to conclusively label it as such. It doesn’t make a whole lot of sense for Christianity to bring an egg-laying bunny into its mythology, but no one really knows when (or why) Peter Rabbit hopped into existence. He simply shows up in Germany during the 1600’s fully formed and passing out eggs. Was the Germanic Oschter Haws (or Osterhase) an echo from the pagan past in the then Lutheran present? Attempts to link him to earlier Christian traditions are just as inconclusive as the attempts to link him with ancient paganisms. Rabbits are such a perfect fit for the Spring (baby bunnies! cuteness!) that I don’t really care where the Easter Bunny comes from.

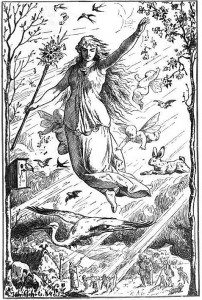

Eostre was a young, Germanic fertility goddess. Of all the questions having to do with Easter/Ostara this is the hardest one to answer. The only mention of Eostre as a goddess in antiquity is from the historian Bede. According to Bede the entire month of April was once named after Eostre (Eoster-month), and eventually this was whittled away until only the commemoration of Jesus’s resurrection was associated with the name. There are reasons for believing in Eostre, and those reasons have a lot to do with the first half of her name. Eos translates as dawn, heck there’s even a Greek goddess of the dawn with that name. Some scholars have suggested that “Dawn deities” can be traced back to the Indo-Europeans (which is a linguistic grouping, not a racial one) but when it comes to Eostre there are far more questions than answers. There are no Eostre myths or artifacts, puzzling if she was a widely worshipped deity. Last year English linguist Phillip A. Shaw argued that Eostre was most likely a localized British goddess, perhaps related to other Germanic cults of matron goddesses. The historical Eostre as a matron goddess? That’ll take some getting used to!

Eostre was a young, Germanic fertility goddess. Of all the questions having to do with Easter/Ostara this is the hardest one to answer. The only mention of Eostre as a goddess in antiquity is from the historian Bede. According to Bede the entire month of April was once named after Eostre (Eoster-month), and eventually this was whittled away until only the commemoration of Jesus’s resurrection was associated with the name. There are reasons for believing in Eostre, and those reasons have a lot to do with the first half of her name. Eos translates as dawn, heck there’s even a Greek goddess of the dawn with that name. Some scholars have suggested that “Dawn deities” can be traced back to the Indo-Europeans (which is a linguistic grouping, not a racial one) but when it comes to Eostre there are far more questions than answers. There are no Eostre myths or artifacts, puzzling if she was a widely worshipped deity. Last year English linguist Phillip A. Shaw argued that Eostre was most likely a localized British goddess, perhaps related to other Germanic cults of matron goddesses. The historical Eostre as a matron goddess? That’ll take some getting used to!

Easter Eggs. Human beings have been eating eggs (and most likely using the shells) before recorded history, so they have a long history and one that cuts across dozens of cultures. Ancient pagans both decorated eggs and imbued them with spiritual meaning. Gods were literally hatched out of eggs, showing them to be symbols of birth and new life. Eggs were decorated and shared as a form of congratulations under the Roman Emperor March Aurelius in the Second Century. According to legend a hen laid a speckled red egg on the day of his birth, a prophesy that the infant would one day become Emperor. It’s also likely that people were passing out decorated eggs even before Aurelius.

Easter Eggs. Human beings have been eating eggs (and most likely using the shells) before recorded history, so they have a long history and one that cuts across dozens of cultures. Ancient pagans both decorated eggs and imbued them with spiritual meaning. Gods were literally hatched out of eggs, showing them to be symbols of birth and new life. Eggs were decorated and shared as a form of congratulations under the Roman Emperor March Aurelius in the Second Century. According to legend a hen laid a speckled red egg on the day of his birth, a prophesy that the infant would one day become Emperor. It’s also likely that people were passing out decorated eggs even before Aurelius.

Christians may have picked up the custom as a result of the egg’s popularity in the Second Century, but there are other possibilities too, and all of them might be why people celebrate Easter with colored eggs today. In the Middle Ages Catholic priests were given eggs as an offering (and form of payment for services rendered) especially around the Easter holiday, and often those eggs were shared via baskets. In Russia, Orthodox Priests gave colored eggs as gifts, later the custom was picked up by the royal family and eventually the rest of the country. English children begged for eggs at Easter during the Seventeenth Century, and most likely carried baskets while doing so. Eggs certainly have nothing to do with Jesus, but are so common it’s impossible to say with any certainty exactly when and why they became linked to Easter in every culture.

Like all modern holidays the customs and traditions associated with the modern Easter most likely arose from a combination of sources: ancient pagan, Christian, and secular. Without those three influences the holiday would look very different today.