One hundred years ago today, a small, lonesome little bird passed away at the Cincinnati Zoo. A few decades before this would have been a death of no note; there had been millions of her sort darkening the skies in impossibly large flocks. But on September 1, 1914, Martha, the very last passenger pigeon, died quietly in her cage.

How did a species that was so numerous less than fifty years before just disappear from the face of the planet? Two factors seem to have been the culprits: habitat loss from human expansion, and overhunting for passenger pigeon meat sold commercially. Indeed, these malignant twin forces have caused the endangerment and extinction of countless species over the centuries as human population has exploded, and the demand for land and other resources has grown accordingly.

Birds in the Victorian era faced an additional threat: demand for their feathers. Feathered hats had become exceedingly popular; individual plumes, whole wings, and even entire bird skins were slapped onto millinery confections and sold at a profit. The plume trade became a goldmine, and a feather hunter could retire on the skins of a few particular species. Some species suffered more than others; the great egret almost went extinct because they only grew their magnificent (and much-desired) plumage during the breeding season. Killing an egret almost certainly meant the death of its young, since both parents were needed to incubate the eggs and care for the young once hatched, and this had a predictably detrimental effect on their ability to recover from the impact of rigorous hunting.

Yet we still have egrets today; populations have rebounded, and they’re listed as of “least concern” by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Why? In 1918, just four years after Martha’s passing, the United States, Canada, Mexico, Japan and Russia passed the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA). This federal law made it illegal not only to hunt almost all wild birds that migrated among at least two of those countries, but even possessing their feathers and other remains was prohibited. Only scientists and other professionals could apply for a permit otherwise. It still stands today, and if I were to pick up a blue jay feather on a walk, I would be breaking federal law.

In order to understand the MBTA, you have to put yourself back a hundred years. Think of the furor over the impending extinction of the rhinoceros or tiger, and the loss of certain subspecies thereof. Now imagine that same threat being imminent for numerous songbirds, raptors, corvids and others, even in your own back yard. There were people who felt just as strongly about endangered species in 1914 as we do today in 2014. And they wanted to make very sure that no more birds went the way of the passenger pigeon. They won that battle and gained us a valuable weapon for the ongoing fight.

Earlier this year, the Patheos Pagan channel asked whether pagan environmentalism had failed. I was in the midst of a lot of work during that time, and so I didn’t get a chance to comment (though my co-blogger, Rua Lupa, had some good things to say). The main thrust of the overall topic was whether we had failed because it seems as though climate change is an inevitability. While climate change is the Big Bad of environmentalism right now, in part because of its far-reaching effects, it’s only one of many overlapping issues under the “environmentalism” umbrella.

See, it’s easy to get discouraged and overwhelmed because we do still face a lot of threats to the environment from numerous directions, and sometimes it feels like the steepest uphill battle imaginable. But part of that is due to the media; the coverage of environmental issues is overwhelmingly negative, and we don’t get to see so much about the victories. And so most of the writings on Martha’s passing will likely be full of gloom and doom, mourning the loss of species gone extinct in the past 100 years, and bemoaning the fates of those close to extirpation. And there’s room for that, to be sure.

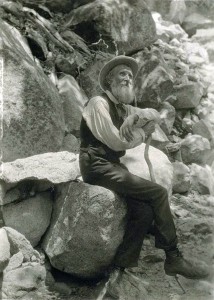

We still lose species at an alarming rate. But worldwide we care more than we used to, and we’re making more efforts to save the ones that remain. Martha’s passing came at a time when most people still saw the environment as a set of resources for human use, and when the voices of conservationists like John Muir were pushing the nascent environmental movement out of its crib and into the media for the first time. We’ve managed to bring environmental issues further into the spotlight than ever before, and while that’s predictably resulted in everything from backlash to greenwashing, we can’t discount the progress that’s been made.

Moreover, we need to pay attention to the progress. One of the biggest threats to environmentalists is burnout. And one of the biggest contributors to burnout is hopelessness brought on by focusing too long on the negatives, the challenges, the problems. We have to remind ourselves of the victories and the ground gained for our own good. This keeps us energized and ready to keep fighting for what we hold dear.

So today I’m not going to sit and mourn for the loss of the passenger pigeon. Instead, I’m going to meditate on how far we’ve come in a hundred years, and visualize what I’d like the world to look like a hundred years from now.