Are you going home or having family over for Christmas with trepidation because it means dealing with a drunken parent? Are you not going home for Christmas because, after years of discomfort, you’re not willing to put up with it anymore?

I’ve been writing about coping with alcoholism and addiction for years and people sometimes ask about the parallel issue: dealing with a loved one who’s an addict or alcoholic. As many of us prepare to visit family for the holidays, I’ll talk a little about the alcoholic or addict parent.

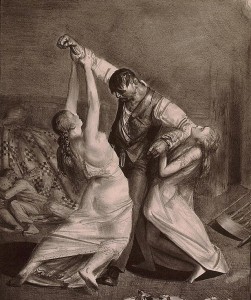

Before my parents passed away, Christmas meant visiting their home. And, among other things, dealing with my dad’s alcoholism. My dad was usually a pretty harmless drunk, getting gradually mellower and eventually passing out. But occasionally he would become rageful instead. And though he never resorted to physical violence, that is an all too common result when alcohol simultaneously fuels anger and loosens inhibitions. (Being of pilgrim and pioneer stock, my own parents’ more common choice of “aggression” was shunning — the silent treatment — which could last for days.)

But family holidays meant more drinking than usual, and it meant my dad tried to stay up and engaged. This combination meant an “incident” or two — of anger or inappropriateness — was likely.

Unpredictability

All families are dysfunctional in various ways. We’re all flawed. But when a parent is an active alcoholic or addict, it can pour gasoline on the mix. Perhaps the most difficult issue is unpredictability. Will the parent be mellow or rageful, happy or depressed? Having the rules shift under your feet creates a lack of feeling safe. You can think you’re OK, and next thing you know, you’re being yelled at. You can know you deserve to be in trouble and have it totally overlooked.

This unpredictability and irrationality in authority figures can also damage a child’s respect for them. From a pretty early age, I was aware that my father’s reasoning abilities were worse than my own (when he was drunk), removing most of the incentive to follow his rules or respect his guidance. Children need and want structure — not harsh or cruel structure, but an appropriate predictable framework.

You might have heard the term “adult child of an alcoholic,” abbreviated as ACOA or ACA. There is a whole subculture in the recovery movement devoted to it. (Though it was much bigger in the 80s, and unfortunately, much of the support there is unhelpful — amounting to little more than feeding a sense of victimhood.)

True forgiveness, true recovery

True recovery from the damage of growing up in an dysfunctional home comes from getting to a place where it no longer continues to harm you. “Resentment” comes from the Latin sentire, to feel, and it literally means to re-feel an incident from the past. The only one being harmed is you. And despite aphorisms like “time heals all wounds,” the damage to family relationships caused by harms done in the past rarely fades on its own. As Rick Warren said so crisply, “Delay only deepens resentments and makes matters worse. In conflict, time heals nothing; it causes hurts to fester.”

The reason most people never let go of the hurt done by a parent is that they never take the essential step of forgiveness. That’s not surprising; forgiveness is hard. But forgiveness is not excusing what happened or defending it. To forgive is to let go of the desire to punish, to look past the harms done and see that of God within the other person. To put it bluntly, the alcoholic or addict parent did they best they could. The “best they could” may not have been good enough — it may have been inexcusable — but it was still the best they could. This is a difficult concept, especially if the harm they did crosses the line from bad parenting into violence or incest. And I’m not suggesting anyone put themselves in a situation they consider unsafe. But if, through prayer and meditation and spiritual counseling, you are able to see the parent as a damaged soul like you, then you can start to let go of the past and not be controlled by it anymore. Because ultimately the point is not what they did; the point is how you can live happily today.

With a decade of self-help work under my belt, I was stuck in a place where I was controlled by my resentments and hurts with my parents. And I had plenty of ammunition. At the height of my father’s alcoholism, he threw me out of the house in a rage at 15 while my codependent mother stood by, and I lived on the streets of New York as a homeless teenager. This would seem unforgivable. It was certainly inexcusable and, I think, illegal. But after going deeper in my spiritual work I came to a place where I could wholeheartedly say that I forgave them. As absurd as it is, I know they didn’t see any other option, and I see how painful it was for them too.

Most people, instead, keep re-feeling the hurt, nurturing their resentments with a sense of entitlement until in many cases the relationship is nearly or completely severed. Unfortunately, in many circles this is celebrated as taking care of yourself.

But what about current harms?

Of course, I’ve been talking about letting go of past harms. But what about the current ones? What if visiting your parents for Christmas means submitting to new abuse? Familial responsibility does not mean putting up with abusive verbal attacks or inappropriate situations.

It’s important to be generous about this, but also to have your eyes open. In my case, I believed the holiday visits in later years were marred only by minor incidents — seeing my dad fall over while everyone pretended they hadn’t noticed (it’s called denial, people), or putting up with a brief drunken argument. But years later, I was told point blank that there was inappropriate behavior I was unaware of, or unwilling to see.

If the alcoholic parent’s behavior is in the category of annoying or disturbing rather than hurtful, maybe you can let it slide. In my post about dealing with politics and religion at family holiday events, I offered some suggestions for dealing with conflict that might be helpful here, and I wrote this post with 6 concrete tips for navigating a dysfunctional family gathering — that is, all family gatherings.

Parented by God

The damage of an inconsistent, untrustworthy or unrespectable parent has another dimension. Many with such backgrounds find it hard to embrace the idea that they are loved and cared for by the ultimate authority figure, especially when the metaphor used to talk about God is that of a parent. Why would you turn your heart and soul over to the care of God the Father when your only experience of a father wasn’t safe or supportive?

Self-help often talks about self-parenting the damaged inner child. I’m talking about something else entirely. Both relationships — that between you and your parent, and that between you and God — can be repaired together.

Compassionately seeing our parent as a flawed child of God who may not have had the tools to be a decent parent, we let ourselves be parented by God, humbly submitting to divine grace moving within us, guiding us to become the adult we were meant to be. In this way, no longer needing from our earthly parent that which they cannot give, we can build a new relationship with them, free of resentments over their shortcomings.

Have you found other ways to make the best of spending holidays in an alcoholic home? Or of repairing the relationship with a parent? Has having grown up with a problematic parent hurt your relationship with God? Share your experiences and thoughts in the comments below.

You can see all my Advent-themed pieces together at patheos.com/blogs/philfoxrose/tag/advent/. Please share this link, or just one to my blog, with anyone you think might be interested. Thanks!