The dead soldier is America’s invisible scapegoat. And all living soldiers are sacred because they “risk their life” for our freedom. What!? A scapegoat? Yes.

For Christians, Jesus Christ is the Final Scapegoat because his death on the cross puts an end to the distorted delusion that some mechanism of sacrifice can purify us. But the cessation of such sacrifice has not yet come. We continue to sacrifice. Americans sacrifice their young people in uniform. To justify this, Americans steal the symbols of salvation from Christianity. It’s all quite invisible even though it lies before our very eyes.

In the service of discourse clarification within public theology, this is the fourth in our treatments of sin: (1) Sin? Really? (2) Sin and Self-Justification; (3) Sin and the Visible Scapegoat; plus (4) Sin and the Invisible Scapegoat. What’s next? (5) Sin Boldly! The regrettable task of the public theologian is to make the invisible visible.

I have been relying on the scapegoat theory of René Girard. I add something to Girard’s theory, namely, the distinction between the visible and invisible scapegoat. Fasten your mental seat belt. We’re in for a bumpy ride.

You are not going to like what you read here. Our topic is original sin. But we are not going to blame Adam and Eve for our situation. Rather, we are going to simply make an observation. When you and I were born, we were born into a society already engaged in invisible scapegoating. We cannot avoid participating. It’s communal sin. We inherit sin and we pass it on. We are bound to sin. Only grace can free us. But, then, that’s another story. Right now, let’s give our attention to the invisible scapegoat mechanism.

Visible and Invisible Scapegoats

In a previous Patheos column, I described how a scapegoat becomes visible through cursing. We curse our nation’s enemies, immigrants, people of color, white privilege, and nearly all those in power. What is invisible is the scapegoat mechanism itself, even if the scapegoat victim is quite visible. (Scapegoat painting by Holman Hunt)

In this Patheos column, we turn to the invisible scapegoat. Here both the mechanism and the scapegoat-as-victim remain invisible. Unless you are willing to have your eyes shocked with the light of a new revelation, please stop reading here.

Barack Obama celebrates America’s sacred soldier

Let me begin with an example and then offer an interpretation. On Memorial Day, 2011, President Barack Obama (2008-2016) honored U.S. soldiers at an event I call a “civic liturgy.” In his oration, the president linked today’s warriors into a chain with our first patriots in the Revolutionary War of 1776. Then he linked this chain with God’s holy word. “What binds this chain together across the generations, this chain of honor and sacrifice, is not only a common cause — our country’s cause — but also a spirit captured in a Book of Isaiah, a familiar verse, mailed to me by the Gold Star parents of 2nd Lieutenant Mike McGahan. ‘When I heard the voice of the Lord saying, ‘Whom shall I send? And who will go for us?’ I said, ‘Here I am. Send me!’” Regardless of the specific text, the mere allusion to Holy Scriptures in a political speech connotes sacred presence, blessing, and reverence.

The inspiring power of the president’s rhetoric is gained by stealing symbols from the Bible for his own political agenda. The call of God to the biblical prophet has become transmogrified into the call of America to the soldier. Whereas the ancient Hebrew prophet answered God’s call to deliver the divine word, America’s soldier answers the same divine call to enter into combat. To fight for America is a holy calling, implied the president.

There is more. This secular sermon on Memorial Day 2011 continued. With an ascending rhetorical crescendo, the president ritually recalled the sacrifices that founded his nation. Patriotic sacrifice stands on the same level as religious sacrifice. Or, perhaps more precisely, patriotism becomes the spiritual bond. “That’s what we memorialize today. That spirit that says, send me, no matter the mission. Send me, no matter the risk. Send me, no matter how great the sacrifice I am called to make. The patriots we memorialize today sacrificed not only all they had but all they would ever know. They gave of themselves until they had nothing more to give. It’s natural, when we lose someone we care about, to ask why it had to be them. Why my son, why my sister, why my friend, why not me?’…We remember that the blessings we enjoy as Americans came at a dear cost; that our very presence here today, as free people in a free society, bears testimony to their enduring legacy.” To sacrifice for America’s freedom is to offer the ultimate sacrifice. There is none higher. And we today–those of us who are Americans–enjoy the blessings of the salvation wrought by our soldier’s sacrificial blood.

Beneath the clever rhetoric that disguises the symbol stealing, something lies hidden, namely, the invisible scapegoat. That scapegoat is the U.S. soldier. This allegedly secular nation is stealing the power of redemption associated with the death of Jesus Christ and transferring it to the death of the American soldier. The soldier dies, so that Americans might live in freedom. The redemptive power of death expressed in today’s patriotism represents the theft by the state of what was once a Christian symbol, the cross. Rather than the visible Jesus, the dead soldier is America’s invisible scapegoat.

Does the blood of the dead soldier really save us?

There is no theological warrant for believing that the blood sacrifice of any soldier in battle has redemptive power. Yet, American’s want to believe this. Why? Because the sacred status of the dead soldier provides the religious foundation for the secular nation. Without this foundation, all would crumble.

Another president violates the sacred

The late Doug Adams, one of my former faculty colleagues at the Graduate Theological Union, would frequently invite us to join his treasure hunt. The treasure? What we deem sacred. How might we know when we’ve found the sacred? You know you’ve found the sacred, said my friend Doug, when you can’t laugh at it.

No one dare laugh at the dead soldier. No one dare even to speak in anything but hushed and reverent tones.

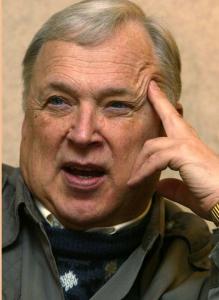

President Donald Trump (2016-2020) stumbled into this truth. In 2018 then President Trump canceled a visit to the Aisne-Marne American Cemetery near Paris. Why? Trump turned down the visit because he feared his hair would become disheveled in the rain. According to four senior staff witnesses, the president exclaimed, “Why should I go to that cemetery? It’s filled with losers.” Also, on the same trip, Trump referred to the more than 1,800 marines who lost their lives at Belleau Wood as “suckers” for getting killed (Goldberg, September 3, 2020). Trump had inadvertently crossed an invisible barrier into the quicksand of sacred power.

The media began to replay an interview where Donald Trump proclaimed–regarding John McCain who had been captive in North Vietnam for five years–, “He’s not a war hero. He’s a war hero because he was captured. I like people who weren’t captured.”

Then POTUS candidate Joe Biden, whose son Beau had volunteered to join the U.S. military and won the Bronze Star in Iraq, declared that his son was not a “sucker.” Military service is a “sacred duty,” Biden trumpeted. The government has a “sacred” duty he repeated. Yes, the soldier—especially the dead soldier—is sacred. But, this sacrality is invisible despite the fact that the word, “sacred” is spoken so frequently in public.

Shedding our soldiers’ blood for the nation’s salvation. Really?

Despite the symbol theft by today’s politicians, very few Christian theologians have dialed 911 to report the crime. One exception is Jürgen Moltmann. This German theologian sees how symbol stealing works in his own country. The practice of stealing Christian symbols to support nationalism began with Roman Emperor Constantine in the 4th century, he says. “The first model of self-sacrifice was that of the Christian martyr in the times of Christian origins who gave his or her life for Christ and with Christ for the gospel and the faith. The martyr followed her or his conscience and, in discipleship of Christ, stood at the side of poor and oppressed people. The Constantinian change of affairs turned the Christian martyr into the Christian soldier….The crown of the martyr was changed into the medal of honor for bravery and victory. In this way the death of the soldier received a religious halo, and it was sanctified and glorified by the understanding that they died that we may live. They died for us” (Moltmann, 2006, p. 261).

Whereas the visible scapegoat is an enemy we curse and kill, the invisible scapegoat is a friend whose death we sanctify. Both scapegoats create and sustain communal bond. The dead soldier blinds and binds. “The origin of any cultural order involves a human death and that the decisive death is that of a member of the community” remarks Girard (Girard R. , 1972, p. 256). The sacrificial death of the scapegoated soldier redeems the nation.

In the United States, the opaque yet masterful rhetoric of sacrifice blinds while it binds the American people. And blood gets shed in perpetual war in order to purify the “land of the free.” The dead soldier is America’s invisible scapegoat.

How does Jesus’ death unmask the lie?

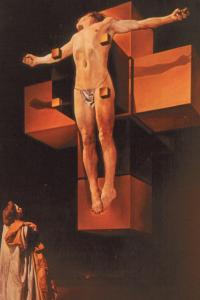

Looking at Jesus’ death on the cross through Girard’s lenses, we might think of the entire New Testament as a funeral eulogy for Jesus of Nazareth. But this eulogy differs greatly from those delivered by American heads of state. Jesus differs from the soldier in that he did not engage in national defense, or even self-defense for that matter. He did not elect to perpetuate the cycle of violence that creates or sustains communal unity. Rather, the New Testament remembers his death as standing in judgment against those who would sacrifice a scapegoat. The Bible stands against declaring the scapegoat sacred and demanding peoplehood or nationhood or patriotism in his name. The Bible tries to remove the blindfold that blinds and binds. (Painting by Dali)

The public theologian recognizes that the death of Jesus desacralizes the scapegoat. “Christ became a scapegoat in order to desacralize those who came before him and to prevent those who come after him from being sacralized,” observes Girard (Girard R. , The One by Whom Scandal Comes, 2014, p. 44). The New Testament memory of Jesus dismantles any community oriented around the sacred; and it does so by exposing the ugly truth regarding how this or any community is established or sustained. The death of Jesus makes visible what had been invisible. The death of Jesus shocks us with truth, with revelatory truth. One of the clear messages of the New Testament that becomes habitually garbled, muddied, and twisted in modern civic and moral rhetoric is this: No more scapegoats!

▀

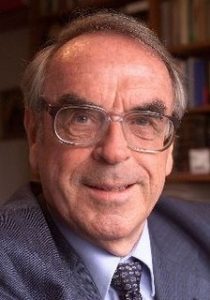

Ted Peters is a pastor, professor, and author of both fiction and nonfiction. Visit: TedsTimelyTake.com.

Ted is emeritus professor of systematic theology and ethics at Pacific Lutheran Theological Seminary and the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley, California. He co-edits the journal, Theology and Science at the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences. His fictional thrillers feature an inner-city pastor, Leona Foxx, who courageously challenges the structures of political domination weaponized by science and technology.

▀

Works Cited

Girard, R. (1972). Violence and the Sacred. Baltyimore MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Girard, R. (2001). I Saw Satan Fall Like Lightening. Maryknoll NY: Orbis.

Girard, R. (2014). The One by Whom Scandal Comes. East Lansing MI: Michigan State University Press.

Goldberg, J. (September 3, 2020). Trump: Americans Who Died in Ware are ‘Losers’ and ‘Suckers’. The Atlantic, https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2020/09/trump-americans-who-died-at-war-are-losers-and-suckers/615997/.

Hammerton-Kelly, R. (1992). Sacred Violence: Paul’s Hermeneutic of the Cross. Minneapolis MN: Fortress Press.

Moltmann, J. (2006). The Cross as Military Symbol for Sacrifice. In M. Trelstad, Corss Examinations: Readings on the Meaning of the Cross Today. Minneapolis MN: Augsburg.

Peters, T. (1992). Atonement and the Final Scapegoat. Perspectives in Religious Studies 19:2, 151-181.

Peters, T. (1993). Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society. Grand Rapids MI: Wm B Eerdmans.

Peters, T. (2015). Sin Boldly! Minneapolis MN: Fortress Press.

Reilly, K. (2016, September 10). Read Hillary Clinton’s ‘Basked of Deplorables’ Remarks About Donald Trump Supporter. Time , pp. https://time.com/4486502/hillary-clinton-basket-of-deplorables-transcript/.

Schwager, R. (1988). The Theology of the Wrath of God. In P. Dumochel, Violence and Truth: On the Work of Rene Girard (p. 51). Stanford CA: Stanford University Press.