Religious Transhumanism? Maybe.

Methodist Religious Transhumanism? The Door is Open a Crack.

H+ 13 / 2023

Transformation is what transhumanists and Christians both pursue. Should these two partner? Or, more specifically, let’s ask Methodist theologian Alan Weissenbacher whether H+ posthumanism could partner with Christian sanctification to make “Methodist Transhumanism.”

In this series on religious transhumanism and its critics, we have interrogated theologians from the Roman Catholic, Mormon, Jewish, UU, Buddhist, and Evangelical Christian traditions. Now, it’s time for the Methodists who have one of the most developed doctrines of transformation, namely, the pursuit of Christian perfection.

Transformation, Methodist Style

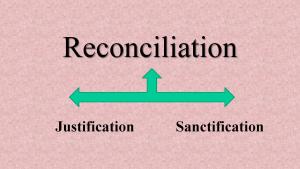

Since the Protestant Reformation, systematic theologians have found it difficult to get straight on what words mean. The key words that need attention are justification, sanctification, and reconciliation. Here’s how Methodist architect John Wesley designs the Christian life.

First, justification is instantaneous. Second, sanctification follows justification. And, sanctification takes time. Once sanctification has been completed, then we are reconciled to God. Some Lutherans quibble about sanctification as a process. Yet, sanctification along with deification (in the Eastern Orthodox tradition) as a process leading to holiness is the dominant view.

Second, Wesley asks: “But what is it to be justified?” He answers: “It is not being made actually just and righteous. This is sanctification, which is indeed in some degree the immediate fruit of justification, but nevertheless is a distinct gift of God, and of a totally different nature. The one implies what God God does for us through his Son, the other what he works in us by his Spirit” (Wesley, Justification by Faith 1984, I.87).

Here’s the point. Justification is instantaneous and immediately salvific. Wesley, however, emphasized that in normal situations justifying faith is intended to be salvific in the broader sense of beginning the process of deliverance from the power as well as the guilt of sin. It is in the moment of justification that sanctification begins. Then, sanctification continues and continues on the road to Christian perfection.

The process of sanctification is what Christians know as transformation from being sinful into becoming holy, loving, and godly. Sanctification begins “in the moment a man is justified. Yet sin remains in him…till he is sanctified throughout” (Wesley, A Plain Account of Christian Perfection 1952, 33). When the sanctification process is completed, the justified sinner becomes perfect. To be perfect is to be “sanctified throughout” (Wesley, A Plain Account of Christian Perfection 1952, 30)

The process of sanctification is what Christians know as transformation from being sinful into becoming holy, loving, and godly. Sanctification begins “in the moment a man is justified. Yet sin remains in him…till he is sanctified throughout” (Wesley, A Plain Account of Christian Perfection 1952, 33). When the sanctification process is completed, the justified sinner becomes perfect. To be perfect is to be “sanctified throughout” (Wesley, A Plain Account of Christian Perfection 1952, 30)

Third, Christian Perfection. What does it mean in this life to be perfect? It means to feel love and only love toward God and one another. “Pure love reigning alone in the heart and life, this is the whole of scriptural perfection” (Wesley, A Plain Account of Christian Perfection 1952, 52).

Fourth, when we add justification and sanctification together, we get reconciliation. For the Reformed tradition, reconciliation is the inclusive term that includes justification and sanctification. Our concern with the Methodist here, however, is the Wesleyan emphasis on sanctification and Christian perfection. This is where the transformation takes place. This is where we ask: is a Methodist transhumanism is conceivable?

Meet Alan C. Weissenbacher

Dr. Alan C. Weissenbacher served many years as a pastor to homeless addicts, removing them from the urban setting and empowering them to run a farm while receiving counseling, spiritual care, and job training. His work with these clients inspires his research into neuroscience and spiritual formation, exploring ways to improve religious care and addiction recovery through understanding how the brain works. He is currently the managing editor of the academic journal Theology and Science.

TP. Alan, what definition or version of transhumanism do you work with? Identify one point where your Methodist theology connects and one where there is a disconnect or even a repulsion.

AW. I see transhumanism as amplifying existing human attributes or adding new ones – making people more intelligent, moral or athletic either through technology or bioenhancement (genetic engineering or brain alteration for example). It is probably good that I am not in a lab as I would probably be fascinated by the idea of giving humans an armored carapace or eagle vision or to create an octopuppy. This does not mean that it is a good idea though, just a tempting one.

I became interested in this idea as a teen in the 1990s through a science fiction series by Dan Simmons that explored the idea of genetically engineering people to enable the colonization of non-earthlike worlds instead of terraforming those words to be earth-like.

Turning to Methodism, there are many diverse views and theological positions in modern Methodism. This diversity of views is highlighted by the fact that the Methodist church itself is looking at a split currently. So, I cannot speak to all Methodism. However, I can highlight some salient points by looking at the theology of John Wesley, the founder of Methodism.

Where Wesleyan theology connects with H+ is in the grand vision that people can transform to be better, act better, do better.

One area of disconnect is related to Wesleyan theology’s strong commitment to the poor. Transhumanism is likely to exacerbate economic inequality, where only the affluent are able to enhance their abilities and reap the benefit, and generational poverty becomes more entrenched as the poor lose any hope of competing with the superhuman.

A second area of disconnect is in how the moral bioenhancement discussion is often framed as an issue concerning individuals and not communities. In his Sermon on the Mount, Discourse 4, Wesley states, “Christianity is essentially a social religion, and that to turn it into a solitary one is to destroy it.” The whole means of transformation is different between Wesleyanism and H+. Transformation is something that is done in and through community, not the lab. Additionally, Christianity is much less about self-transcendence than it is other-centered.

TP. What does transformation look like from a Methodist perspective? How does John Wesley connect such things as justification, sanctification, and Christian perfection? How do you define Christian perfection?

AW. For John Wesley, moral development is not merely about external matters such as avoiding evil, doing good, and participating in the means of grace. These external matters are driven by the emotional dimension of human life, and it is here where healing is needed. This is not meant to devalue outward moral action, but rather explains a person’s ability to perform moral outward actions adequately, if at all.

Christian transformation is to habituate and develop holy emotions directed toward a proper act and end. Once transformed, holy actions then flow naturally from holy emotional dispositions. A Wesleyan virtue ethic states that the sanctification process is about training virtuous emotions and habits within community so that moral decisions become second nature. This is a gradual process involving continued repentance, reliance on grace, and active community involvement, both in doing good works that transform us and allowing the community to get all up in your business to encourage positive transformation and critique areas where you fall short.

TP. Do you believe that human enhancement through technology—superintelligence through gene editing, Artificial Intelligence, Intelligence Amplification, and such—will contribute to Christian perfection?

AW. I have my doubts. It is false to automatically equate greater intelligence or greater technological progress with greater morality. You can look at recent history to disprove that. We might just get smarter criminals and more efficient means of destroying others. Some of the greatest impediments to making moral decisions are not a lack of intelligence, but rather what are described psychologically by the HALT risk states – being hungry, angry, lonely, or tired. This is typically used in addiction therapy to describe the states where the addict is most likely to relapse or act out. We could focus instead on genetically addressing issues of anger management, but then, what about those times where anger is appropriate, such as a motivating factor to address societal injustice? Empathy has a strong correlation with caring behavior toward others, but then, if we enhance it, could we end up with such a degree of empathy where no one is able to sleep at night or accomplish basic life tasks because people are so emotionally crippled by the suffering around them?

TP. Under what conditions might a Methodist positively incorporate the H+ vision of the posthuman into the doctrine of sanctification?

AW. I think Methodism will need to struggle with the question on how technology and bioenhancement can serve as a means of grace. God can sanctify people through many means and is one of these bioenhancement? And then if it can be seen as a means of sanctification, which forms of bioenchancement – some? all?

One aspect that can be embraced heartily is engaging with technology that involves people in transformative experiences for virtue development. For Wesley, a prime way for people to transform their emotions was for them to seek out experiences that engage the area of needed transformation. Need to work on compassion, do acts of compassion. Need to work on anger, face angering situations while concentrating on love and forgiveness. As the imagination is often as formative as reality in terms of character development, VR can confront people with situations and experiences that can enable character development, provided you had the proper orientation and debriefing so as to prime the proper lesson.

TP. Is Methodist Transhumanism viable? Any final thoughts?

AW. For a short summary, technological progress, yes – provided it doesn’t fragment community. Moral bioenhancement — qualified no, as there are strong areas of repulsion, but the Wesleyan highlight on inner emotional transformation in the sanctification process leaves a door open a crack.

Methodist Religious Transhumanism? Conclusions

Another item not said here but very valuable is this. Alan Weissenbacher provides helpful advice for pastors and theologians tempted to engage in neurotheology. Here is his warning: do not take at face value what neuroscientists, neurophilosophers, or neurotheologians say! Be critical. Neuro-determinism is misleading, he says.

Even so, there are many pastoral hints that we can gain from genuine neuroscience. Take advantage of them.

In summary, Alan Weissenbacher opens the door just a crack so that the potential blessings of transhumanism can sneak into the Methodist pursuit of Christian perfection.

▓

Ted Peters directs traffic at the intersection of science, religion, and ethics. Peters is an emeritus professor at the Graduate Theological Union, where he co-edits the journal, Theology and Science, on behalf of the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences, in Berkeley, California, USA. He authored Playing God? Genetic Determinism and Human Freedom? (Routledge, 2nd ed., 2002) as well as Science, Theology, and Ethics (Ashgate 2003). He is editor of AI and IA: Utopia or Extinction? (ATF 2019). Along with Arvin Gouw and Brian Patrick Green, he co-edited the new book, Religious Transhumanism and Its Critics hot off the press (Roman and Littlefield/Lexington, 2022). Soon he will publish The Voice of Christian Public Theology (ATF 2022). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

Ted Peters directs traffic at the intersection of science, religion, and ethics. Peters is an emeritus professor at the Graduate Theological Union, where he co-edits the journal, Theology and Science, on behalf of the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences, in Berkeley, California, USA. He authored Playing God? Genetic Determinism and Human Freedom? (Routledge, 2nd ed., 2002) as well as Science, Theology, and Ethics (Ashgate 2003). He is editor of AI and IA: Utopia or Extinction? (ATF 2019). Along with Arvin Gouw and Brian Patrick Green, he co-edited the new book, Religious Transhumanism and Its Critics hot off the press (Roman and Littlefield/Lexington, 2022). Soon he will publish The Voice of Christian Public Theology (ATF 2022). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

His fictional spy thriller, Cyrus Twelve, follows the twists and turns of a transhumanist plot.

▓

Bibliography

Gouw, Arvin, and eds. Brian Patrick Green and Ted Peters. 2022. Religious Transhumanism and Its Critics. Lanham MA: Rowman and Littlefield / Lexington.

Redding, Micah. 2022. “Why Christian Transhumanism?” In Religious Transhumanism and Its Critics, by Brian Patrick Green, and Ted Peters, eds Arvin M Gouw, Chap 7. Lanham MA: Lexington.

Weissenbacher, Alan. 2018. “Artificial Intelligence and Intelligence Amplification: Salvation, Extinction, Faulty Assumptions, and Original Sin.” In AI and IA: Utoppia or Extinction?, by ed Ted Peters, 69-88. Adelaide, Australia: ATF.

Wesley, John. 1952. A Plain Account of Christian Perfection. London: Epworth.

Wesley, John. 1984. “Justification by Faith.” In The Bicenntennial Edition of the Works of John Wesley, 35 Vol;umes, by ed. Frank Baker, Volume 1. Nashville TN: Abingdon.