How does Jesus save?

Part Four: The Satisfaction Theory of Atonement

ST 2004

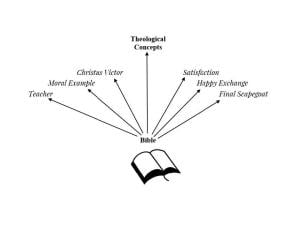

How does Jesus save? Well, there’s more than one answer. We’re looking at six. Each is a relatively coherent motif or model or theory of atonement within systematic theology. But, they’re not in competition with one another. In this post, we look at the Satisfaction Theory of Atonement.

Here’s the list we’re working with. How does Jesus save? Part One: Introduction

- Jesus as teacher of true knowledge

- Jesus as moral influence

- Christus Victor

- Jesus as victorious champion

- Jesus as liberator

- Jesus as Satisfaction

- Recapitulation Theory

- Satisfaction Theory

- Penal Substitution Theory

- Happy Exchange

- Jesus as the final scapegoat

In this post, we will ready ourselves for the vigorous controversy especially within the Reformed tradition over the Penal Substitution Theory or PST. But first, I need to make a preliminary point, namely, PST is a variant on the Satisfaction theory. What’s the Satisfaction Theory? Just read on.

In this post, we will ready ourselves for the vigorous controversy especially within the Reformed tradition over the Penal Substitution Theory or PST. But first, I need to make a preliminary point, namely, PST is a variant on the Satisfaction theory. What’s the Satisfaction Theory? Just read on.

4.a. The Satisfaction Theory of Atonement

Recall our earlier observation that what we find in the New Testament are many different families of metaphors each of which answers in a different way our question: how does Jesus save? (Hultgren 1987) The sacrifice of the lamb of God is one way the New Testament speaks of atonement. Lamb imagery is drawn from a family of metaphors: shepherd-sheep-lamb-scapegoat. On the one hand, the lamb or scapegoat is sacrificed (1 Corinthians 5:7). On the other hand, the Good Shepherd sacrifices his life for the flock (John 10:11-18). Is this a contradiction? No. Multiple metaphors make the same point in New Testament texts. Systematic theology interprets the biblical symbols to formulate rational doctrine.

Progressive Christian Patheos columnist Richard Murray also suggests that these symbols can be oxymoronic. He deconstructs the “wrath of the lamb” in the book of Revelation. “The wrath of the Lamb.” This phrase is oxymoronic because lambs don’t have wrath, at least in any sense with which we are familiar. Thus, the Lamb imagery subverts all traditional notions of wrath.” Members of this family of symbols tumble over each other in suggestive and heuristic ways.

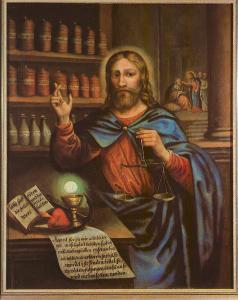

Two other families of metaphorical motifs are relevant to atonement. One is the forensic family with terms and concepts such as law, justice, justification, judge, condemnation, and such. A second is the healing family with Jesus’ healing miracle accounts plus and terms such as disease, illness, sickness, leprosy, healing, soteria. Our term, Soteriology, derives from the healing metaphor.

We do not expect the agglomeration of biblical symbols to make coherent sense on their own. It is up to the systematic theologian to reflect on the biblical symbols and lift them up into a coherent ontological or metaphysical theory.

3.a. Recapitulation Theory

Austria 18th C., Heidelberger Schloss. Reliance here on biblical symbols of Jesus as healer.

The Recapitulation Theory draws primarily on the family of biblical metaphors dealing with illness and healing. The fall into sin is like an illness. Alienation from God is like a disease. By taking the world’s disease up into the life of the incarnate Jesus Christ, the world gets healed.

If you ask, what is the Eastern Orthodox view of the atonement?, here is a forceful answer.

“The Recapitulation Theory agrees that God needed to deal with man’s sin. Man was separated from God as a result of the fall and, left to his own devices, was incapable of returning to God. However, Recapitulation sees the model through which God dealt with man’s sin as a hospital rather than a courtroom. Instead of viewing the atonement as Christ paying the price for sin in order to satisfy a wrathful God, Recapitulation teaches that Christ became human to heal mankind by perfectly uniting the human nature to the Divine Nature in His person. Through the Incarnation, Christ took on human nature, becoming the Second Adam, and entered into every stage of humanity, from infancy to adulthood, uniting it to God. He then suffered death to enter Hades and destroy it. After three days, He resurrected and completed His task by destroying death.”

The history of the human race is recapitulated in the life of Jesus, thereby returning the fallen world to its original state of grace.

What follows for you and me is the process of divinization or theosis. Divinization entails cleansing or healing from sin. It entails becoming Christlike. Even though divinization recapitulates our primeval creation, it is actually a future “superlative fulfillment beyond mere restoration to primordial innocence” (Ray, 1997, 26).

In the Eastern Byzantine tradition, Christ’s recapitulation relies on metaphors of disease and healing. In the Latin tradition of the West which includes both Roman Catholics and Reformation Protestants, we find relatively greater reliance on forensic metaphors. St. Anselm’s satisfaction theory of atonement illustrates this vividly.

3.b. Anselmian Satisfaction Theory

Interpreting the forensic metaphors in scripture in terms of an ontological or metaphysical worldview is most dramatically illustrated in the intricate theological twists and turns taken by the medieval theological pioneer, Saint Anselm of Canterbury (1033-1109). Anselm bequeathed to us the satisfaction theory of atonement.

Anselm’s variant on the satisfaction model of atonement draws indirectly on the shepherd family of symbols and directly on the forensic family. The theory begins with a giant assumption, namely, the universe created by God is ordered by the principle of justice. What is the anthropological or hamartiological problem? The order of divine justice that governs the cosmos has been disturbed by the introduction of human sin. How can the disorder cosmos be returned to its ordered state? That is the way Anselm formulates his version of our question: how does Jesus save?

Here is the answer that logic requires, according to Anselm: God must perform an act whereby the just order is fulfilled—that is, is satisfied.

Anselm’s work Cur Deus Homo? published in 1098 raised the question of the incarnation: Why did God become human?

Like Augustine before him, Anselm thought of systematic theology as faith seeking understanding (fides quarens intellectum). Anselm wanted to understand the why of the incarnation.

Anselm also had in mind an apologetic mission: to demonstrate convincingly to nonbelievers that the doctrine of the atonement makes rational sense. So, he set out to prove the necessity of the incarnation using reasoning alone apart from any prior historical knowledge regarding the work of Christ (remoto Christo). Let us briefly review the essential stages of Anselm’s argument.

The Just Order of the Universe

God’s purpose for creating the human race emerges out of God’s infinite love and compassion. So, from the beginning God planned for us to enjoy perfect blessedness and happiness. Even felicity. And, the order of justice in the universe would provide the mechanism to accomplish this goal. The blessedness God aimed at would require the total and voluntary harmony of our own will with the divine will, for it is upon God’s will that the very harmony and beauty of the just universe rest. But, through an act of defiant willing, the human race has chosen disobedience. The human race has chosen injustice. This human injustice has fractured the cosmic harmony and frustrated God’s plan for our happiness.

Justice requires that any deviation of our will must be balanced by a deprivation of blessedness. The imbalance can be righted in one of two ways: either through punishment and denial of blessedness or through an act of satisfaction whereby an offering is rendered up that is greater than the act of disobedience. Note: either punishment or satisfaction (aut poena aut satisfactio). God does not want to follow the road of punishment because God’s purpose is to bestow blessedness. Therefore, satisfaction becomes God’s preferable solution.

But this leads to a dilemma. On the one hand, unconditional forgiveness is not an alternative, according to Anselm. Why? Because such an act would introduce further irregularity into God’s universe. On the other hand, no member of the human race can offer any satisfaction to God because each human is already under the obligation of total obedience. If total obedience is already required, then there is no extra moral or spiritual capital available with which we can redeem ourselves from our past or future sins.

Houston, we’ve got a problem! And, big time! Unless something drastic is done about it, the whole human race must suffer the punishment produced by a disharmonious universe and forfeit the blessedness for which we were created.

Yes, the incarnation is necessary!

Up until this point, we have been working on the premise of divine love, a love that purposed human happiness and that seeks a solution to the problem created by human sin. But now Anselm moves to a second phase in the argument and introduces another premising factor, God’s omnipotence.

It would appear that God’s purpose for the creation has been frustrated. But this is impossible, if God is omnipotent. Therefore, a means of redemption must exist. The offering for satisfaction ought to be made from the human side, but since we have nothing to offer, it cannot be made by us. But God is capable of making such an offering. Because only God is able to make the offering that we ought to make, it must be made by a combination of the divine and the human. Therefore, concludes Anselm, the incarnation is necessary. We know why God became human.

The Gospel Story

Anselm proceeds then to tell the gospel story. The incarnate Son of God freely offers up his sinless life to death in honor of God. But death is a form of punishment to be incurred only as a result of sin. Therefore, because Jesus’ self-sacrifice is an unwarranted deed that the father cannot allow to go unrewarded, and because the Son needs nothing for himself, the reward accrues to the advantage of those for whom the Son dies.

Satisfaction has been accomplished. Whew. We can relax now.[1]

Satisfaction Theory in Reformation Soteriology

Make no mistake. There is no room in Anselm’s satisfaction model to hold that human suffering in itself produces salvation. Sacrificial suffering is not a general principle. Rather, the sacrifice of Jesus Christ repairs a malfunctioning gear in the machinery of cosmic justice (Ray, 1997,63).

Anselm’s Latin theory framed the forensic mindset of the Protestant Reformers in the centuries that followed. Terms such as justice, satisfaction, sacrifice, reconciliation, righteousness, and such combined to frame the gospel story of redemption. Here’s atonement according to the Westminster Confession of 1647.

The Lord Jesus, by His perfect obedience, and sacrifice of Himself, which He through the eternal

Spirit, once offered up unto God, has fully satisfied the justice of His Father; and purchased, not only

reconciliation, but an everlasting inheritance in the kingdom of heaven, for those whom the Father has given

unto Him. (Westminster Confession of 1647, VIII:5)

Not only the Reformed, but also the Lutherans extended the satisfaction framework. In his Commentary on Romans, Martin Luther writes:

Christ’s “death, not only signifies but actually effects the remission of sin as a most sufficient satisfaction. And His resurrection is not only a sign or a sacrament of our righteousness, but it also produces it in us, if we believe it, and it is also the cause of it” (Luther, LW 1955-1986, 25:284).

Note, by the way, that the death makes satisfaction. But, it’s the resurrection that “produces it in us.” The resurrected Christ is mystically placed within us by the Holy Spirit through faith.

When we get to the Augsburg Confession of 1530, satisfaction is dubbed a propitiatory sacrifice. In Article III we find that Jesus Christ “truly suffered, was crucified, died, and was buried that he might reconcile the Father to us and be a sacrifice not only for original guilt but also for all actual sins of human beings” (Book of Concord, 39). Satisfaction is the objective work of atonement accomplished by Jesus Christ on Calvary. When we turn to Article IV Concerning Justification, we turn to the subjective appropriation of atonement within our faith. “Human beings cannot be justified before God by their own powers, merits, or works. But they are justified as a gift on account of Christ’s sake through faith” (Book of Concord, 39-40).

The Lutherans maintain Anselm’s legal or forensic matrix within which atonement and justification-by-faith are framed. Yet, this is only one model employed by Luther himself. We have already reviewed Christus Victor. And, in a later Patheos post, we will examine Luther’s use of the Happy Exchange model.

A Biblical Critique of Satisfaction Theory: Arland Hultgren

Oh, but wait! Let’s hear from the critics of Anselm’s satisfaction model.

Two critics challenge Saint Anselm’s satisfaction theory. One on the grounds that it lacks biblical support, and the other on the grounds that it relies unnecessarily on the principle of redemptive violence.

The biblical critic is New Testament scholar Arland Hultgren of Luther Seminary in St. Paul, Minnesota. It is Hultgren’s judgment that a satisfaction theory cannot be derived from the New Testament. He argues on the grounds that Christ does not “appease the wrath or justice of God” (Hultgren 1987, 175).

Like so many critics of Anselm, Hultgren assumes that the satisfaction theory belongs within the framework of appeasement. He fails to acknowledge that the framework for Anselm is not appeasement. Anselm’s framework is cosmic justice. The problem, says Anselm, is that of just order and how to restore it once sin has brought disorder into the world.

Hultgren’s criticism certainly applies to John Calvin’s Penal Substitution Theory, even if not to Anselm’s Satisfaction Theory. We will see this in our next Patheos post.

A Second Biblical Critique: René Girard

Here is the second of our first two criticisms of Anselm. Stanford literary critic, the late René Girard (1923-2015) , offers a nuanced yet decisive critique, in my judgment. Girard contends that (1) the satisfaction theory depends upon a sacrificial reading of the Christ-event in the New Testament, whereas there is no sacrificial component in Jesus’ death. What?! There is no sacrificial mechanism in the New Testament? Really?

In addition, contends Girard, (2) the satisfaction model founds the Christian social order on a ritual murder, and ritual murder is the core of evil (Girard 1978, 182). The efficacy of the cross in this model depends on redemptive violence, which is just the opposite of the gospel message.

In a later post in this Patheos series, we will take up René Girard’s position in more detail. Girard will discard the satisfaction model and, instead, treat Jesus as the final scapegoat. Girard will still draw from the shepherd-sheep-lamb-scapegoat family of New Testament symbols, but his theory will differ from either the satisfaction model or the Penal Substitution Theory.

Is the moral influence theory better than satisfaction theory?

Anselm’s atonement model has drawn criticism from at least three more directions: Peter Abelard, feminist theology, and Gustaf Aulén. We have seen how the moral influence theory appears as a less bloodthirsty alternative to satisfaction. This alternative was already posed in Anselm’s own era by Peter Abelard. In a previous post I reported that the liberal Protestant tradition has followed Abelard, not Anselm.

Might an Eastern Orthodox theologian combine Anselm and Abelard, incorporating both satisfaction and Jesus-as-True-Teacher? Johnathan Hill seems to.

“So God, because He is just, in His mercy sends His only Son to redeem the world. He satisfies our fallen state by redeeming and reconciling the world both to and in Himself, but also to and in ourselves. He invites us to become co-workers with Him in this great restoration, and, leading us on the way of righteousness, teaches us truth, and ultimately, grants us life everlasting.”

Does God require child abuse for divine satisfaction?

In our era, some feminists have criticized the concept of sacrifice—sacrifice being more prominent in the satisfaction variant of atonement—arguing that its impact on our culture is negative. The satisfaction model presents an image of a dysfunctional heavenly father who demands sacrifice from his earthly son. And, this in turn promotes victimization of women and children who wish to imitate Christ and end up subjecting themselves to patriarchal oppression.

Methodologically, feminist critics contend that metaphors should remain metaphors and not be literalized. In The Atonement Muddle, Ianna Jane Ray warns us against turning a metaphor into a literal dogma.

Methodologically, feminist critics contend that metaphors should remain metaphors and not be literalized. In The Atonement Muddle, Ianna Jane Ray warns us against turning a metaphor into a literal dogma.

“When a metaphor loses its transcendent horizon and instead is taken literally, the literal version of the metaphor loses its former associative, suggestive, ambiguous quality and instead becomes a fixed statement that cannot be challenged” (Ray 1997, 99).

This is just what happened to the Anselmian Satisfaction Theory, complains Ray. “By taking Anselm’s description of the relations between Father and Son literally, the doctrine of creation/fall/redemption-by-substitutionary-Atonement became a mirror validation for violently dysfunctional patriarchal families” (Ray, 1997, 100). A literal rendering of the motif’s metaphors turns theology into a brutal ideology. “According to many contemporary Feminist theologians, Atonement theory is not only ‘harsh and legalistic’, it is downright perverse and sadistic” (Ray, 1997, 100).

Theologians Joanne Carlson Brown and Rebecca Parker raise the accusation of “divine child abuse.” Arguing that we should do away with the idea of atonement entirely, they contend that “the image of God the father demanding and carrying out the suffering and death of his own son has sustained a culture of abuse and led to the abandonment of victims of abuse and oppression. Until this image is shattered, it will be almost impossible to create a just society” (Brown 1989, 9). For Brown and Parker and for Rita Nakashima Brock as well, it appears that it is the cross of Christ itself that needs redeeming (Brock 1988, 56).

This leaves the theologian lost in a thicket of symbolic confusion. The symbol of the cross is intended to liberate, yet it appears to incarcerate. Pacific Lutheran University professor Marit Trelstad attempts to blaze a path through the thicket of abuse and suffering associated with atonement. She affirms that God’s work in Christ is redemptive, but she asks: Just how can we conceive of this atoning work without reenforcing intra-family abuse?

Trelstad answers: by placing the work of Christ within the ontological context of God’s covenant with us: “The contextualization of the cross within an ontological covenant prevents the over-glorification of suffering and the cross that can happen when atonement and soteriology focus solely on the cross. For this reason, it may more adequately address the lives of women in abusive relationships” (Trelsted 2010, 122). On this point, Trelsted follows Anselm himself, who placed the satisfaction work of the cross within the creation covenant where God had originally intended to bless creation through creating a structure of cosmic justice.

In this line of argumentation, Lou Ann Trost at San Jose State University affirms that “the suffering and frequent victimization of women is real and must be addressed.” Yet, she counters that atonement cannot be blamed for this: “For thousands of years before and after Christ suffered crucifixion, male Homo sapiens have not needed the Jewish or Christian idea of sacrifice or suffering in order to keep women submissive.” When atonement is held together by justification by grace through faith, argues Trost, then we can understand how “it is the gospel, the love of God in Jesus Christ, which frees” (Trost 1994).

Gustaf Aulén’s Critique of the Satisfaction Motif

We have just seen how Anselm’s satisfaction model has garnered criticism from Abelard and from feminists. Gustaf Aulén is also a critic. Among his criticisms, the most forceful begins with Aulén’s contention that redemption is the work of Christ as God, not Christ as human: “This is the decisive issue; and, therefore, the crucial question is really this: Does Anselm treat the atoning work of Christ as the work of God himself from start to finish? . . . The contrast between Anselm and the Fathers is as plain as daylight. They show how God became incarnate that he might redeem; he teaches a human work of satisfaction, accomplished by Christ” (Aulén 1967, 86-88).

It is clear that the criterion by which Aulén assesses the various theories of atonement is the Christus Victor motif, according to which the redemptive acts of the incarnate one was really acts solely of God. God acts in Christ in a way that excludes the thought of any atoning work done by Christ as a human. If by Christ we mean the incarnate Chalcedonian Christ with the two natures and the two wills, the one who is fully human and fully divine, then who is Aulén talking about when he says “God” does it? God as Father? God as Logos but just one half of Christ? Such an extreme emphasis places Aulén in the same camp with the monophysites.

The problem with monophysitism (and other similar doctrines such as monergism, monotheletism, and docetism) is that it overemphasizes the role of divinity in Christ to the exclusion of the human. This means risking the loss of true Emmanuelism (God-with-us). Thus, the recoil from firing the cannons of criticism at Anselm throws Aulén farther and farther back on sola gratia, farther and farther back on divine initiative and divine responsibility for the atonement, so that eventually the human nature of Jesus becomes jettisoned and Aulén risks backing himself right off the deck of Chalcedonian orthodoxy.

Is it not the position of Chalcedon that it is the divine word that acts, but that this word has truly become flesh, so that Jesus Christ acts divine et humane—in a divine and a human manner? Is this not precisely what Anselm himself proposes?

Anselm: Therefore none but God can make this satisfaction.

Boso: So it appears.

Anselm: But none but man ought to do this, otherwise man does not make this satisfaction . . . [Therefore] it is necessary for the God-man to make it . . . Now we must inquire how God can become man. The Divine and human natures cannot alternate, so that the Divine should become human or the human Divine; nor can they be so commingled as that a third should be produced from the two which is neither wholly Divine nor wholly human . . . Since, then, it is necessary that the God-man preserve the completeness of each nature, it is no less necessary that these two natures be united in one person, . . . for otherwise it is impossible that the same being should be very God and very man (Anselm 1966, 126-127).

What we have in Anselm’s satisfaction theory of the atonement is a valiant attempt by faith to seek understanding, a significant attempt at evangelical explication of the biblical symbols. It is doubtful, however, given the contextualization principle, that we would wish simply to repeat Anselm’s formulation in our own day and expect it to be adequate to the intellectual context of the twenty-first century.

Nevertheless, we can learn from Anselm (Peters 2015, Chapter 7). If we can get beyond recent theologians’ criticisms of Anselm, we can appreciate the seriousness with which he takes the human predicament and how he employs Chalcedonian Christology to demonstrate the depth and power of God’s compassion expressed in the work of Emmanuel (God with us).

What’s Next?

Anselm’s satisfaction motif sharply distinguished between punishment and satisfaction (aut poena aut satisfactio). By the time we get to the Reformers and John Calvin, punishment and satisfaction have been conflated. By punishing Jesus, satisfaction is rendered to God.

To the Penal Substitution Theory and its critics we turn in the next Patheos post.

How should a systematic theologian answer the question: how does Jesus save?

▓

Ted Peters is a Lutheran pastor and emeritus seminary professor, teaching theology and ethics. He is author of Short Prayers and The Cosmic Self. His one volume systematic theology is now in its 3rd edition, God—The World’s Future (Fortress 2015). His book, God in Cosmic History, traces the rise of the Axial religions 2500 years ago. He has undertaken a thorough examination of the sin-and-grace dialectic in two works, Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society (Eerdmans 1994) and Sin Boldly! (Fortress 2015). Watch for his forthcoming, The Voice of Christian Public Theology (ATF 2022). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

Ted Peters’ fictional series of espionage thrillers features Leona Foxx, a hybrid woman who is both a spy and a parish pastor.

▓

[1] Here is Inna Jane Ray’s summary and interpretation. “In this substitutionary atonement theory, Christ does not obtain victory over the Devil, nor is Christ’s work to turn the deep attention of humankind back to its proper object, God. The work of Christ repairs the damaged honor of God: the work of Christ is placation of God’s wrath” (Ray 1997, 45). I cannot say Ray is wrong. But, her emphasis on placating God’s wrath leaves out what I deem decisive, namely, the structure of justice that guides the universe required repair. This is what satisfaction accomplishes.Bibliography

Abelard, Peter. 2007. “Peter Abelard on the Love of Christ in Redemption.” In The Christian Theology Reader, by ed Alister McGrath, 358-359. Malden MA: Blackwell.

Althaus, Paul. 1966. The Theology of Martin Luther. Minneapolis MN: Fortress.

Anselm. 1966. Cur Deus Homo. LaSalle IL: Open Court.

Aulén, Gustaf. 1967. Christus Victor. New York: Macmillan.

Book of Concord. 2000. Eds., Robert Kolb and Timothy J. Wengert. Minneapolis MN: Fortress.

Brock, Rita Nakashima. 1988. Journeys of the Heart. New York: Crossroad.

Brown, Joanne Carlson, and Rebecca Parker. 1989. “For God So Loved the World?” In Christianity, Patriarchy, and Abuse, by eds Joanne Carlson Brown and Carole R. Bohn, 9. New York: Crossroad.

Calvin, John. 1535. Institutes of the Christian Religion . Tr. Thomas Norton: https://www.ccel.org/ccel/calvin/institutes.toc.html.

Girard, René. 1978. Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World. Stanford CA: Stanford University Press.

Hultgren, Arland. 1987. Christ and His Benefits: Christology and Redemption in the New Testament. Minneapolis MN: Fortress.

Kant, Immanuel. 1960. Religion within the Limits of Reason Alone. New York: Harper.

Luther, Martin. 1955-1986. LW. Luther’s Works, American Edition, 55 Volumes: St. Louis and Minneapolis: Concordia and Fortress.

—. 2016-2019. The Bondage of the Will (1525) / The Annotated Luther, 6 Volumes. Minneapolis MN: Fortress Press.

Peters, Ted. 2015. God–The World’s Future: Systematic Theology for a New Era. 3rd. Minneapolis MN: Fortress Press.

Ray, Inna Jane, 1997. “The Atonement Muddle.” Journal of Women and Religion 15.

Tanner, Kathryn. 2001. Jesus, Humanity, and the Trinity. Minneapolis MN: Fortress.

Trelsted, Marit. 2010. “Putting the Cross in Context: Atonement Through Covenant.” In Transformative Lutheran Theologies, by ed Mary J Streufert, 107-122. Minneapolis MN: Fortress.

Trost, Lou Ann. 1994. “On Suffering, Violence, and Power.” Currents in Theology and Mission 21:1 35-40.